Category: Uncategorized

Interfacing

With the waistband attached and any watch pocket installed, we can go ahead and install the interfacing. There are a couple of ways you could do this. The first would be to take your waistband pattern and cut out the interfacing as one piece from a linen collar canvas, or two (or more) layers of linen. This method (using the collar canvas) gives a firm finish to the waistband. The second way, which I’ll be showing here, involves cutting shorter strips of linen and applying them where you deem necessary, which gives a slightly softer finish to the waistband, depending upon how many layers you add. I’ve used both methods but prefer the second now due to ease of installing and the softer finish.

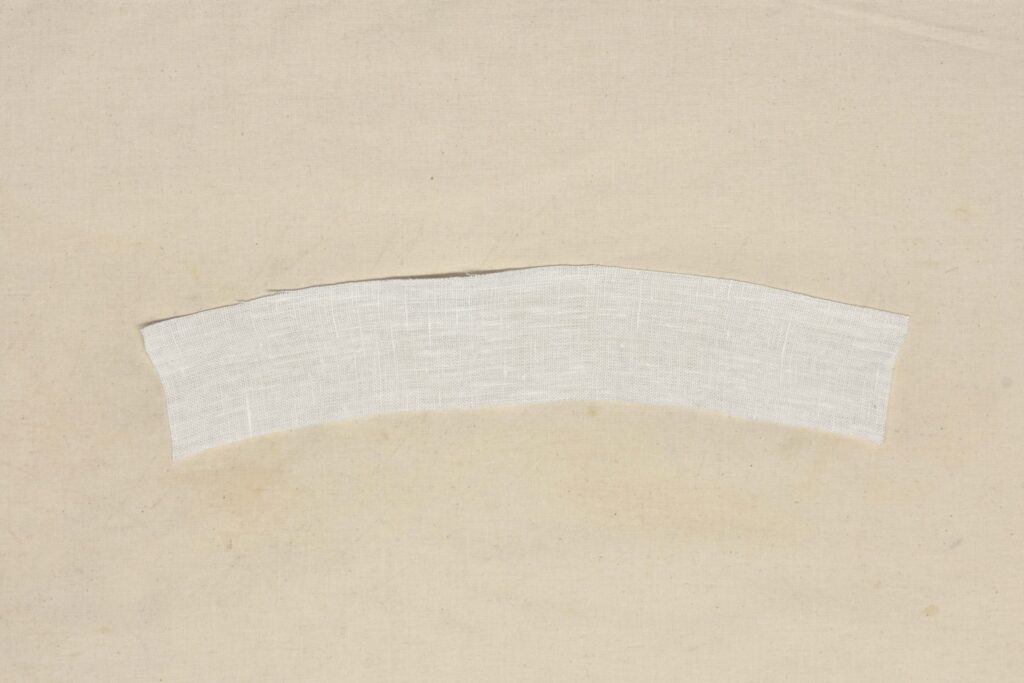

Begin by cutting about 10 – 12 strips of linen, about 3″ wide (or slightly wider than the waistband) and a little longer than half the length of the waistband.

Lay the trousers on your sewing table wrong side up and begin to position the linen strips in place.

Lay the linen on the waistband, lining the bottom edge up with the fold of the waistband seam. Begin basting the linen in place. I set the end of the linen back about 1/4″ from the center back of the trousers since that’s where the seat seam will end up, but you could trim this later as well.

The basting stitches should be roughly centered, but closer to the waistband seam. As you’re working, don’t tuck the linen too tightly into the waistband seam, as you’ll end up with puckers and excess fabric later on.

Place and baste the second piece of linen in place as well, butting the ends of each piece together.

I probably could have gotten these a little closer but the gap will not be noticeable.

At the front edge of the trousers, draw a line parallel to the button catch.

And cut the linen even with the front of the trousers. You could also wait to do this step until all of the linen layers are in place.

Now I like to cut one of the next linen pieces in half for the second layer so that I can keep the joints staggered like bricks for added strength.

You’ll notice how the center of the trousers is somewhat curved. You could take that center piece of linen and stretch it along one edge to form in into a curved shape that will better conform to the shape of the trousers.

Baste one of the smaller linen pieces in place followed by the curved piece. Keep these slightly further back from the waistband seam if you can to reduce the tension and prevent and rippling.

Here’s the second layer of linen in place after trimming both ends.

You could add another full layer as above if you like, but for my third layer, I chose just to reinforce the areas that will have buttons. Over the years, one of the biggest issues I’ve seen is buttons being ripped out of the fabric over time, this will greatly help to prevent that. I added a small piece near the back of the trousers.

And another strip to the front of the side seam over the pocket. Both pieces should be placed even more loosely against the waistband seam, kind of staggering the long edges of each layer of linen.

And here’s one last look at the waistband with all three layers of interfacing installed.

Turn the trousers over and trim the linen flush with the edge of the waistband.

Turn the trousers back over and mark a cut line about 3/8″ from the top edge of the waistband. You could even go a ‘smidge’ further if your fabric or interfacing layers are particularly thick. The 3/8″ accounts for the turn of the fabric, helping us to end up with a 1/4″ finished seam allowance.

Here’s mine after drawing the cut line. As you can see my linen pieces were a bit narrower than they should have been, but it all worked out.

Trim the interfacing to just past the line, cutting through all layers except the waistband itself, of course.

If you haven’t already done so, trim the back end of the interfacing to about 1/4″ to 3/8″ away from the trouser edge, making room for the seam allowance and pressing the seam over later on.

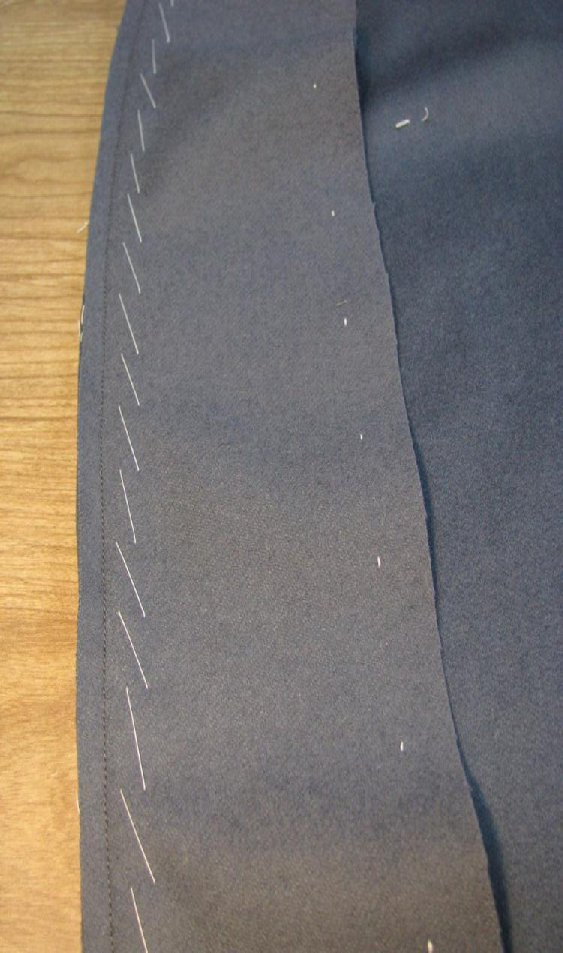

Gently fold the top edge of the waistband over the interfacing and baste securely in place.

If you added the watch pocket, make sure that the side seam pocket bag is in the correct position, and permanently baste it to the waistband seam using small diagonal stitches. This gives a little extra strength to the pocket.

Trim the top edge of the pocket if necessary, even with the waistband seam below it.

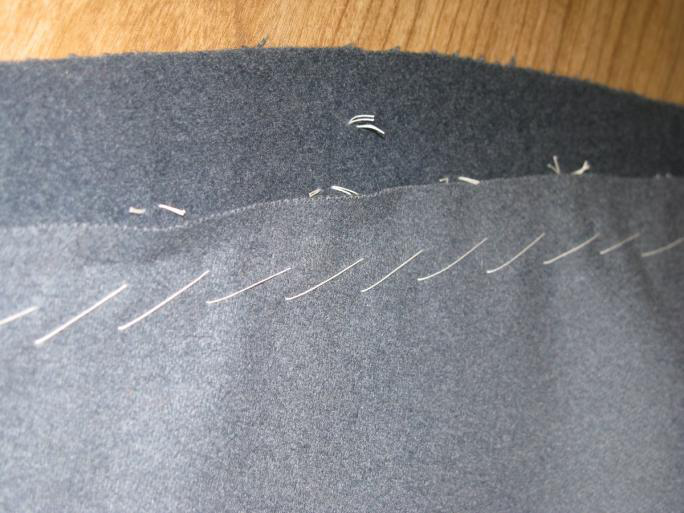

Working from left to right, cross stitch the folded waistband edge to the interfacing underneath. Try to catch all of the interfacing layers without letting the needle pass through to the right side.

Before cross stitching the lower half of the interfacing, make sure that the tension between waistband and interfacing is neutral, without any excess fabric showing up in bubbles or ripples. If you have to (I did), carefully trim about 1/16″ from the lower edge of the interfacing to ease the tension.

Then cross stitch the interfacing to the waistband seam.

And here’s the top of the pocket with watch pocket after cross stitching in the same manner.

Securing the Waistband Ends

With the interfacing cross stitched in place, fold over each end of the waistband over the interfacing, keeping a straight edge as appropriate. Baste in place with a diagonal stitch.

Fold under the raw edges on top and lower edges, setting the top edge back about 1/16″ and allowing the lower edge to just cover the waistband stitch line underneath. Baste in place.

Fell the folded edges of the waistband using a small stitch, keeping the diagonal part of the stitch hidden between the layers.

Cross stitch the remaining waistband edge to the interfacing.

Repeat for the back of the waistband and the other half of the trousers. This completes the installation of the interfacing.

The Top Collar

Begin the top collar by placing the collar pattern on the grain, and chalking the outline. Add a two inch inlay to the top and bottom, and three inches to the sides. You have the option of placing the collar on the fold, or seaming the pieces together. In the case of seaming, you should add a 1⁄4 inch seam allowance, and stitch the pieces right sides together. In my case, I chose to cut the collar in one piece.

Stretch the top and bottom of the top collar with the iron. This will help the collar lay more smoothly on the finished coat.

Lay the top collar right side down on the table, and place the coat in position on top. Use the chalk marks as a rough guide in getting the proper alignment.

Baste from one edge of the collar, about one inch from the edge until you meet the roll line. Continue basting along the roll line until you reach the far edge of the collar.

At the top edge of the collar, about one inch from the edge, baste the top collar to the under collar, making sure there are no ripples in the fabric underneath. Use your fingers to determine this.

Carefully trim the collar ends to one inch, and the top edge to 3/8 of an inch.

Fold the edge of the top collar beneath the under collar, and baste. There should be 1/16” of fabric showing beyond the raw edge of the under collar, so that it will not be visible when completed.

This photo shows the collar so far. Next we’ll secure the stand side of the collar.

Trim both ends of the collar to 3/8 of an inch.

Baste the ends under in the same manner as the top of the collar, making a nice fold at the corner.

On the bottom edge of the top collar, near the gorge line, measure a half an inch seam allowance from the edge of the collar. Trim carefully.

Fold under the fabric and baste along the gorge line. Ideally there will be no pulling or ripples. I ended up going back and redoing this section.

From the gorge line to the point of the collar just before it meets the end of the facing, fold and baste under the fabric.

Here’s what the collar should look like. Note the back section has not been basted down yet.

Turn the coat lining side down again, and baste the stand of the collar from one end to the other.

At the back, carefully slash the top collar so that it may smoothly fit around the curvature of the neck. Don’t slash too far, however. Next, using a pad-type basting stitch and silk thread, baste the top collar to the collar seam below it. These stitches are permanent, so don’t let them show through to the right side.

Lapels and Side Body

It’s now time to begin piecing the coat body together. I prefer to baste everything together before sewing for maximum control. It helps to ensure all the seams line up properly.

Begin by basting the lapels to the forepart, wrong sides together. The lapel should line up with the tailor’s tacks, unless you needed to make some alterations for a protruding stomach, which would then need to be marked.

Before sewing, you should trim off the inlay, cutting directly on the tailor tacks you put in earlier.

Sew the seams with a 1⁄4 inch seam allowance. Press the seam well on each side to set the stitches, then press from the wrong side, and finally from the right side. Using a tailor’s ham in extremely necessary for this seam, or you will lose all of the fullness that forms between the two pieces. All seams should be sewn in this manner.

Note how flat the seam looks. There is no ‘roll’ to the seam. When pressed well, the layers of fabric are almost unnoticeable to the touch.

Note in this photo how the lapel extends a 1⁄4 inch below the forepart. This is due to adding the seam allowance there, which, after experimenting, I recommend not adding.

Side Body

Now baste the side body to the forepart, right sides together. The seams should be the equal in length, but if you’ve stretched the two pieces in unequal amounts, you may have to stretch one of the seams again. Press open, using a tailor’s ham for the lower half.

Note that this is the only inlay that remains in the finished coat, as it is the easiest one to let out if necessary, and does not affect the pressing of the seam.

Fitting Issues

If you wish to do a fitting at this point, you may do so. I wanted to see the affects of some more ironwork I did, and also to check how the back looked after raising it a half inch. Note how the back falls smoothly to the waist now, and how the folds are almost completely gone from the side pieces. What remaining fullness there is will be taken up by the padding later on.

In this photo, you’ll notice that the waist seam is uneven in the front. This is something that occurs on all double breasted coats, even modern coats. To fix, you will need to raise the front waist on the right side of the coat 3/8 of an inch, tapering into the regular seam about 7 inches from the center front, as shown.

At the back, you can see the alteration I did to raise the side body and back waist.

After you are satisfied with the alterations, trim off the inlays following the remarked lines.

Creating a Muslin Toile

Before moving on to stylizing your pattern, it’s a good idea to get most of the fitting out of the way while the pattern is less complicated. To do that, we’ll construct a muslin vest, using inexpensive fabric to check for fitting errors.

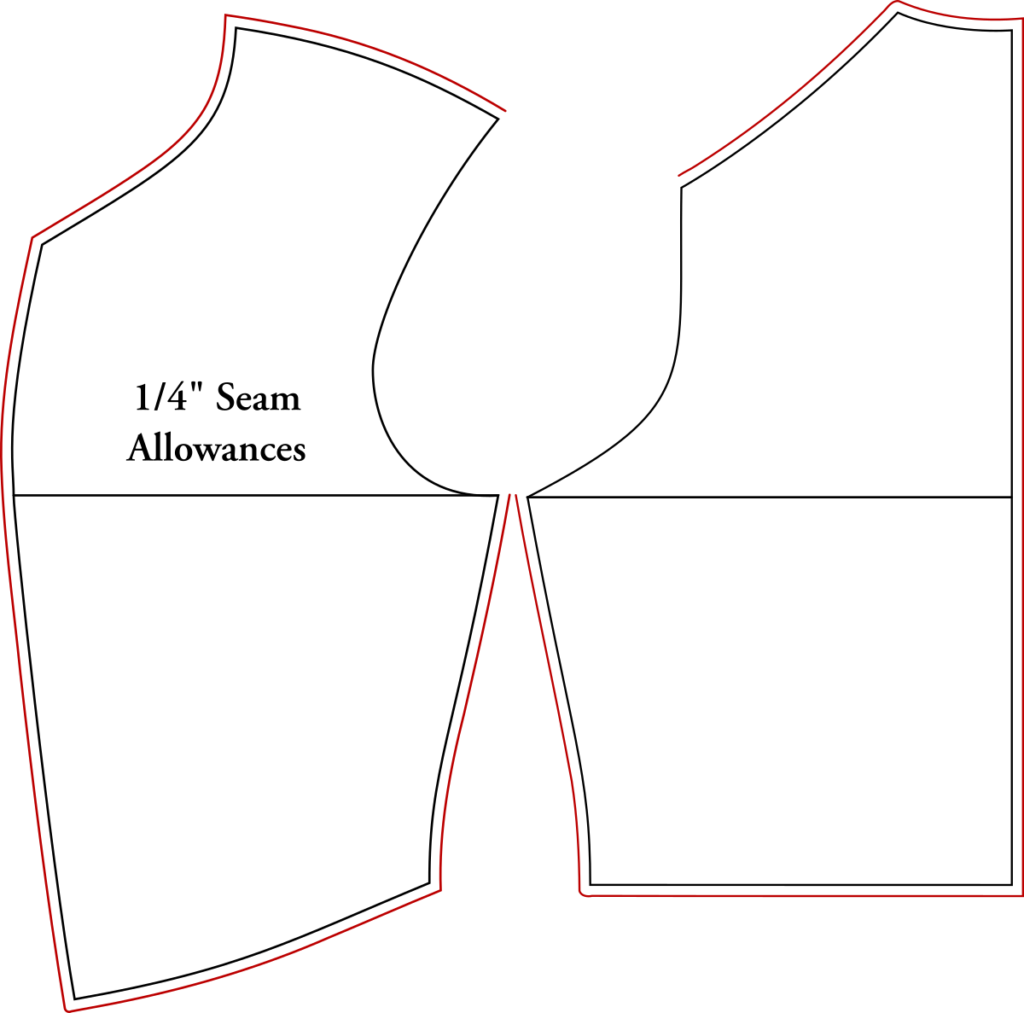

To begin, copy the front and back of your draft onto a fresh piece of paper, so that the original draft can be preserved. After you’ve copied them, seam allowances need to be added. Through a lot of research and experimentation, I’ve come to the conclusion that Devere’s draft needs 1/4″ seam allowances needed along every edge, except the armscye and shoulder seam. And while I personally do not add seam allowances to the shoulder seam, for this beginner course, we will add the 1/4″ there as well, in order to make the construction a little easier. Feel free to leave it off if you wish, though.

Here is a diagram of the pattern pieces after the seam allowances have been added. I use a small ruler to mark out the 1/4″ all the way around. Also be sure to mark out the chest line, to help you align the patterns on the fabric.

Here is my pattern after tracing to a fresh sheet of paper and adding the seam allowances.

Cut out both pattern pieces along the seam lines you just drew, being as neat as possible. Lay the pieces on your doubled layers of muslin fabric, and carefully trace around each piece using sharp chalk or a pencil. Place something on the pattern to hold it in place while you trace. Make sure that the horizontal construction chest line on the pattern is perpendicular to the edge of the fabric to get a good grain alignment.

Cut out the pieces, cutting on the inside of the line to ensure a more accurate fit.

Ironwork

As this pattern is for a generic vest, and we have not yet decided on which fabric to use, we will assume it will be a wool vest for now. To get a good period fit, the shoulder area of the vest fronts were shaped with the iron. As this is a very lightweight muslin fabric, it’s possible to just do this using your hands. Holding the armscye in one hand at the fullest part, at the bottom of the X’s, use your other hand to stretch the material. It’s better to have a lighter touch and make more passes over the length of the armscye.

If you did not add seam allowances to the shoulder area, stretch across the top of the shoulder as well.

With right sides together, lay the forepart and back together, aligning the side seam, and pin at the ends. It’s likely that the forepart will be slightly longer, so place a pin in the middle, dividing the fullness in half, and repeat with another pin between, for a total of 5 pins. Sew the seam using a 1/4″ seam allowance.

Pin the ends of the shoulder seams, right sides together, and subdivide further with more pins. If you left the seam allowance in, there will be a fair amount of fullness to work in on the back. If not, the two seams will match pretty closely in length.

Sew, using a 1/4″ seam allowance. Press open all of the seams with your thumbnail.

Sew the two halves together along the back, right sides together. This completes your vest muslin, which you can go try on and begin to work on any fitting issues you may have. Please post in the forums with photos of your draft, and wearing the muslin, and I’ll help you as best I can through the fitting process.

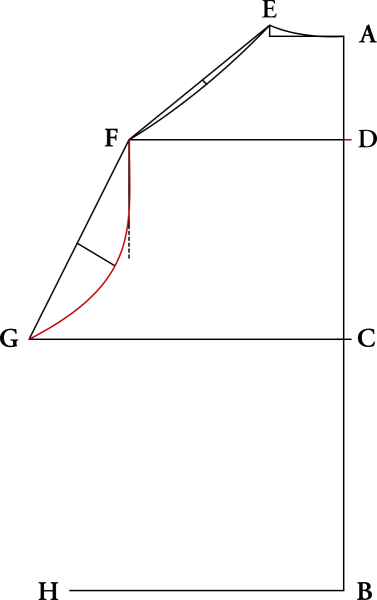

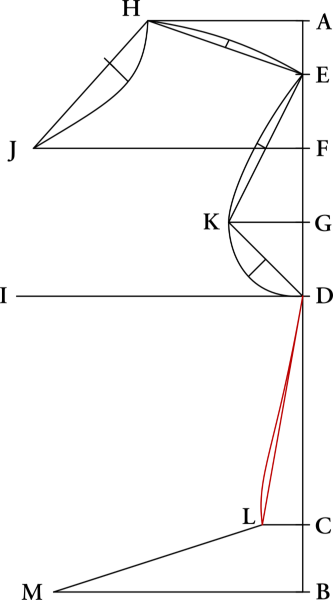

Drafting the Back

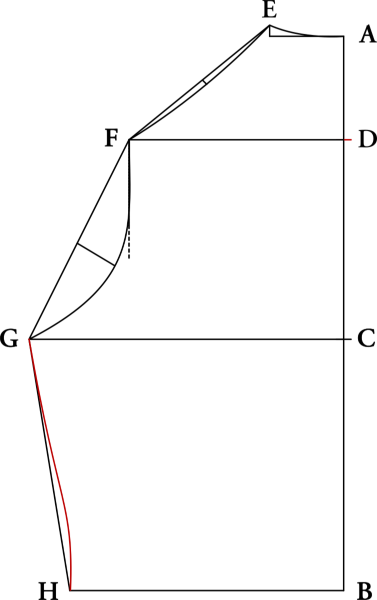

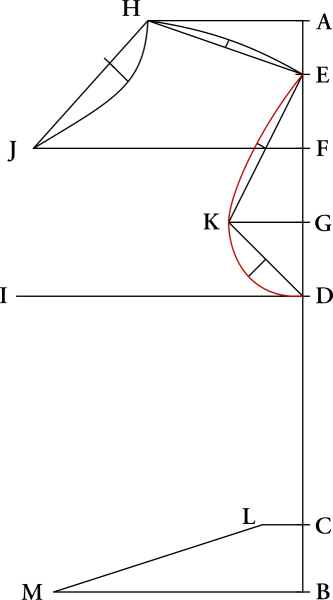

Let us now proceed with drafting the back of the waistcoat. I’d recommend doing this on the same sheet of paper as the front, and align the point A on both front and back, so you can be sure that things are properly lined up while drafting.

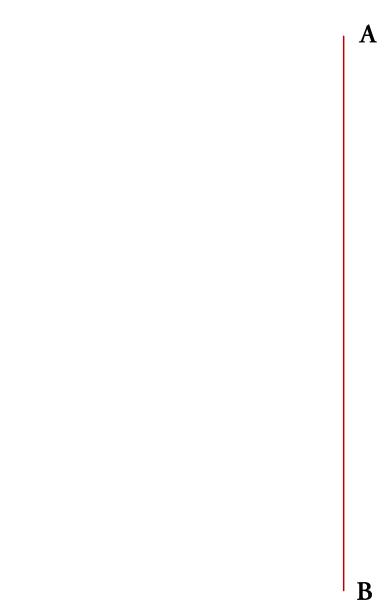

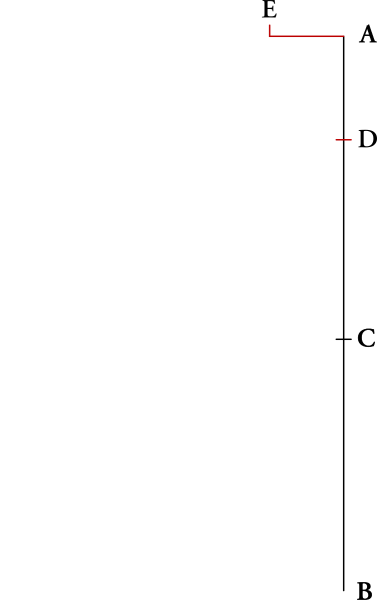

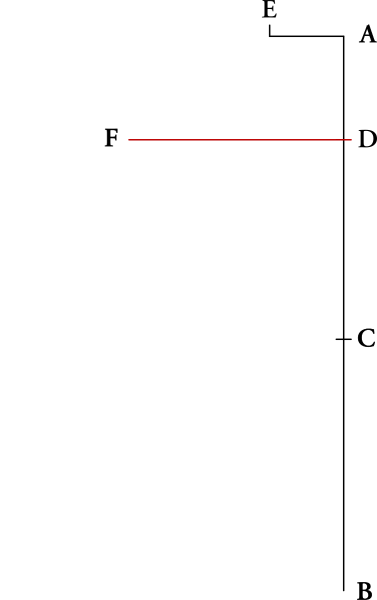

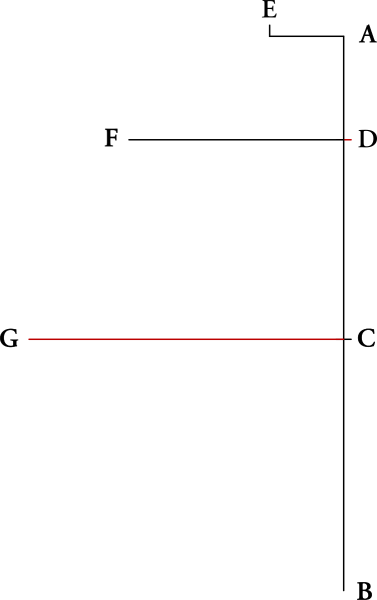

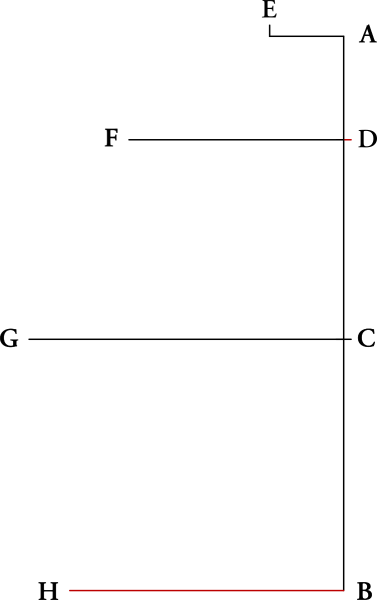

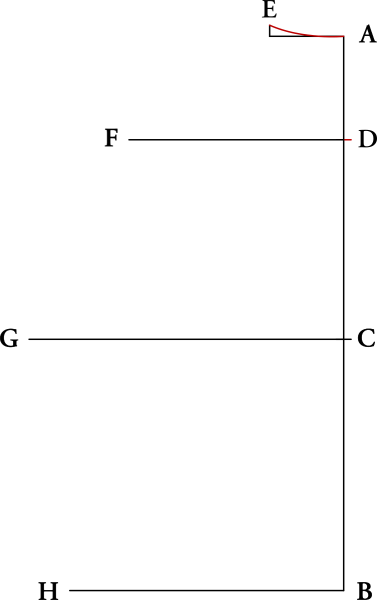

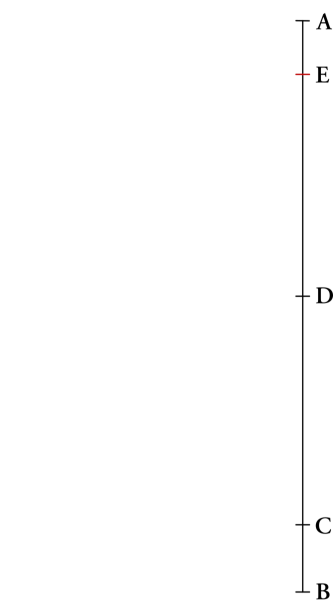

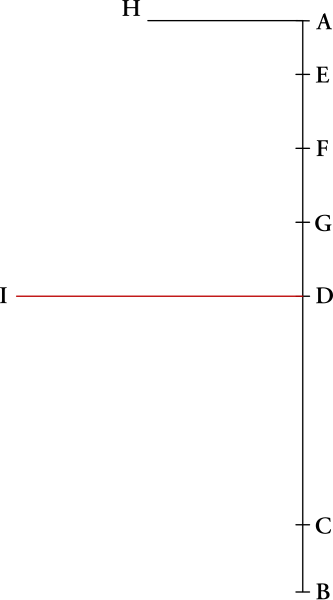

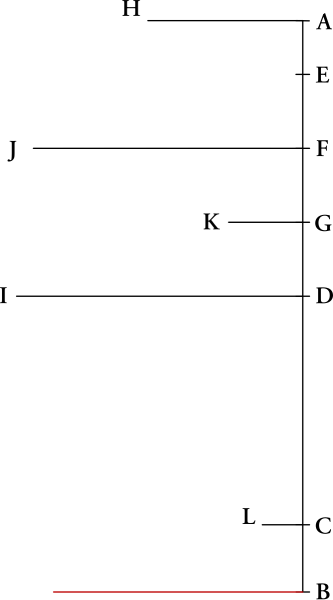

A – B

Draw a long straight line, and mark on it the length of Curve to measure.

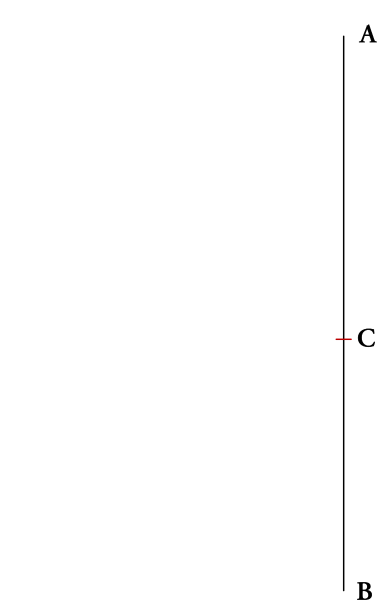

B – C

Length of Side to measure.

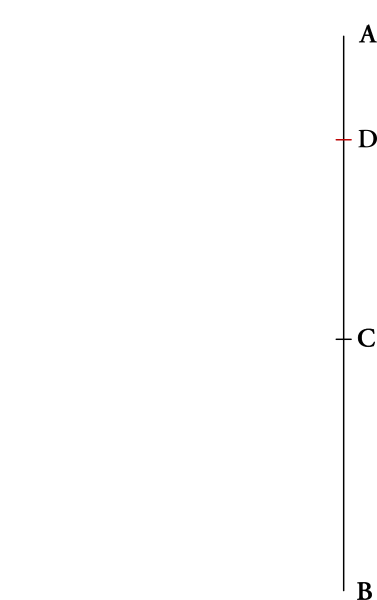

A – D

3 1/2 graduated inches

A – E

Draw a line square across from A to E, which is 2 1/2 graduated inches.

At E, square up 3/8 graduated inches for the rise of the neck.

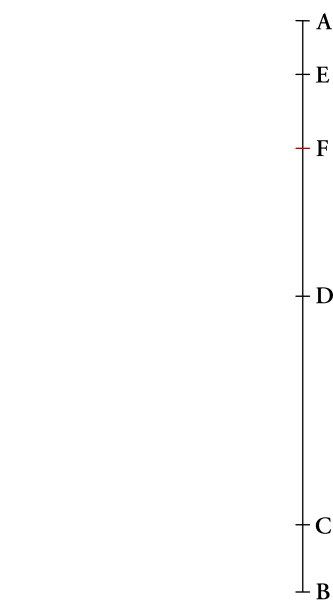

D – F

Square across from D to F, at 7 1/4 graduated inches.

C – G

Square across from C to G, at 10 5/8 graduated inches.

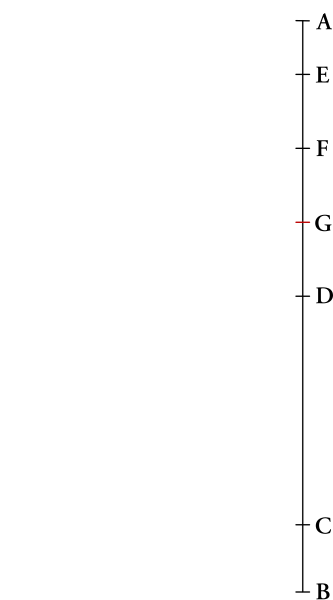

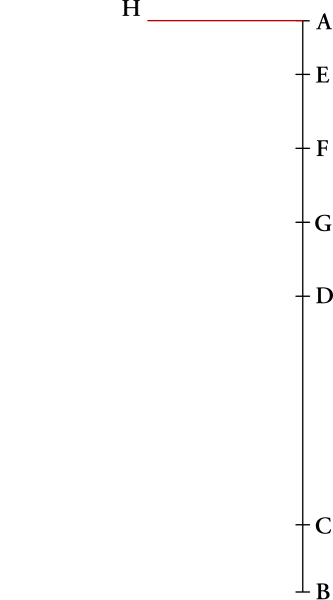

B – H

Square across from B to H, making this length equal to half the waist plus 1 1/2 graduated inches. This extra is added to give extra movement in the back, and is taken up by the strap and buckle during use.

Back Neck Curve

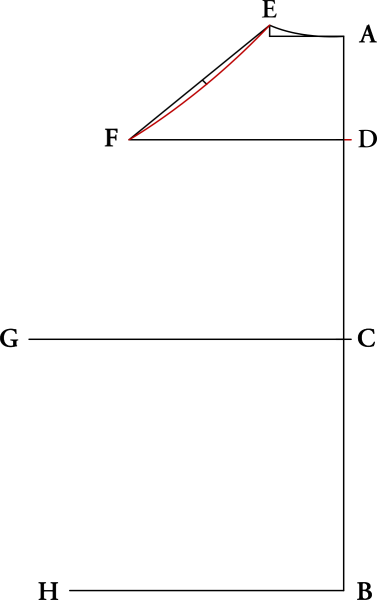

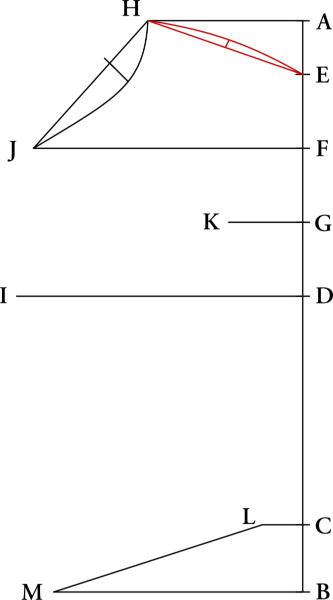

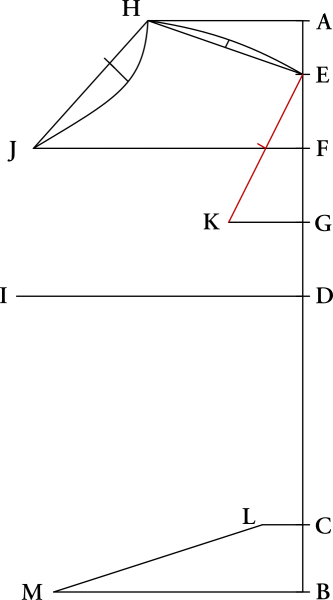

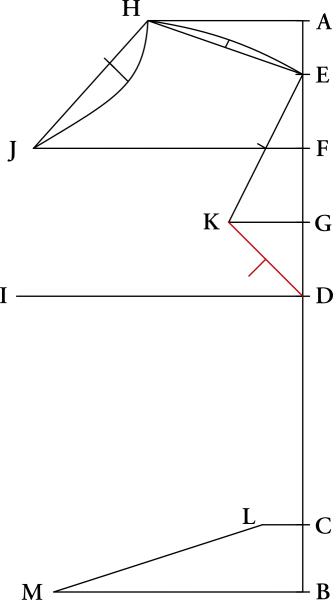

Using a French curve or free hand, draw a curve for the back neck from A to E as shown.

Shoulder Seam Hollowing

Draw a straight line from E to F. Find the center of this line, and draw a 1/4″ line square towards the back at this point. Then draw a curve connecting all three points as shown.

Armscye

Draw a line square down from point F. This is just a construction line to aid in drawing the armscye.

Draw a line from point G to F. Find the middle, and draw a line square at 1 1/2 graduated inches in length. Draw a curve connecting the three points. This curve should align with the construction line you drew previously down from F.

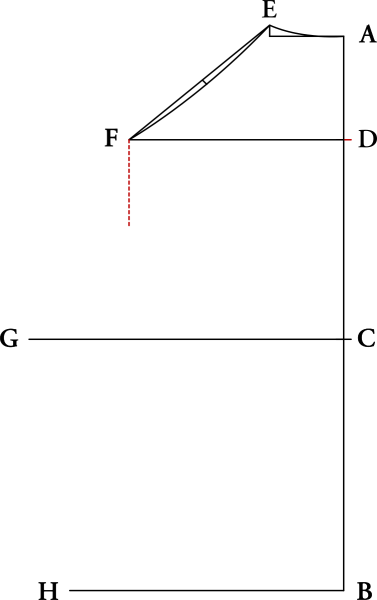

Waist Hollowing

About 2 inches above the waist line, hollow in 1/4″ for the hollow of the waist, and draw a line connecting G, H, and that point. This completes the draft of the waistcoat back.

Your Progress

[columns gutter=”0″]

[col]

1 | Draft the waistcoat back. |

[/col]

[col align_text=”center, middle”]

[/col]

[/columns]

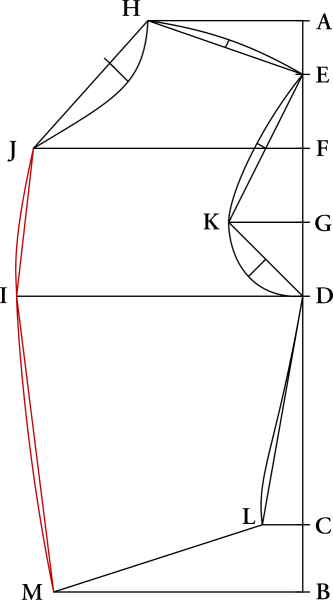

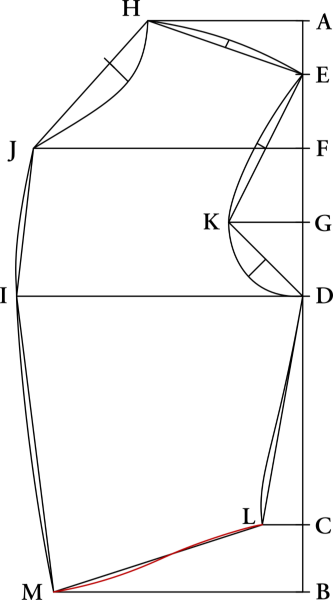

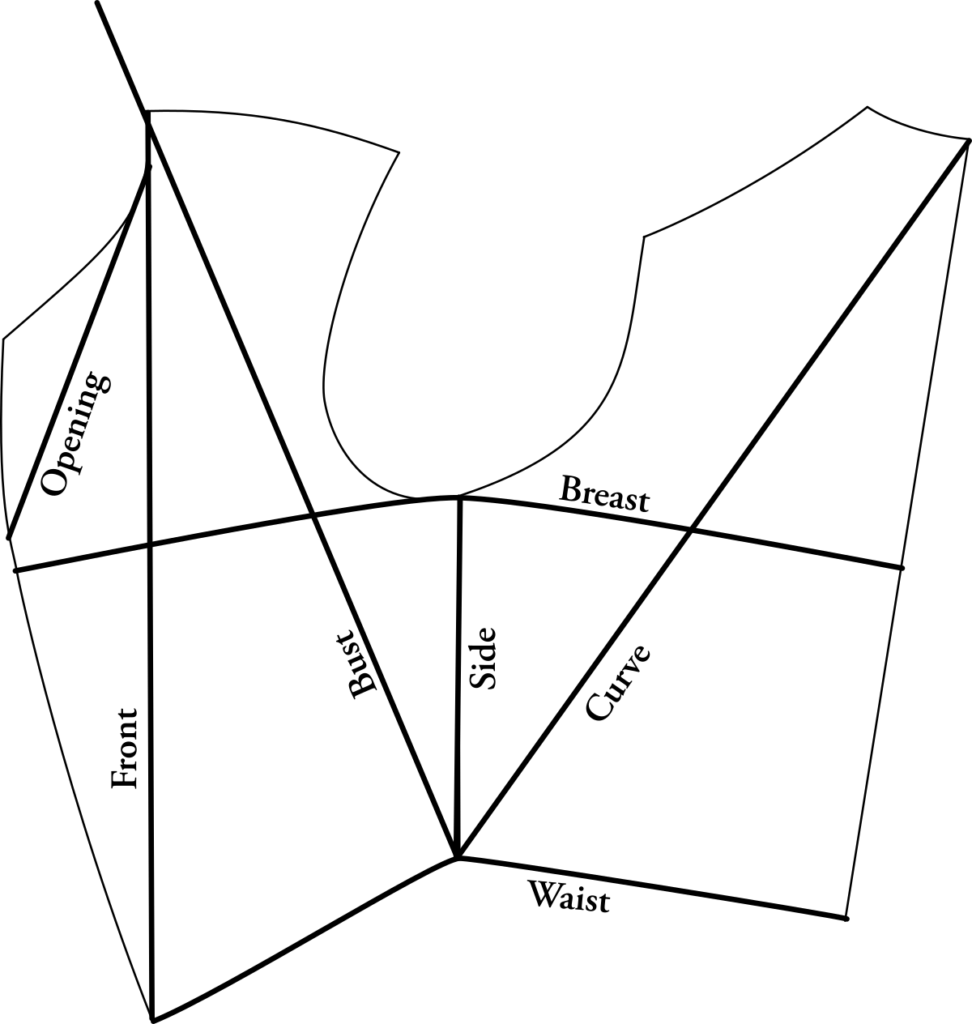

Drafting the Front

Now we’ll begin the drafting process. I like to draft on ‘project paper’, found at most office supply stores. A quilters’ ruler, french curve, and a sharp pencil will help get you started.

If following the instructions below, use a normal ruler or your actual measure when the instructions say ‘to measure’. If graduated inches are specified, use the graduated ruler corresponding to your Breast measurement.

If you prefer to use the spreadsheet, just use the numbers that are calculated for you, and use the drawings here as a guide.

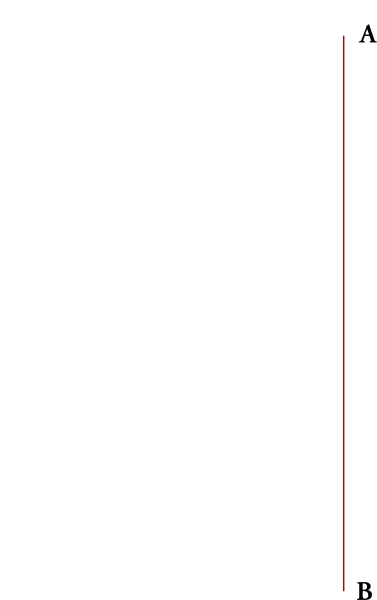

A – B

Draw a long straight line, and mark on it the length of Bust to measure.

B – C

Measure up from B to point C, 2 1/2 graduated inches. This marks the bottom of the side seam.

C – D

Length of Side to measure.

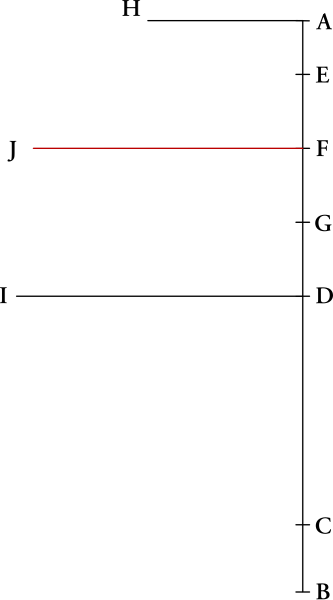

A – E

Mark point E at 2 graduated inches from point A.

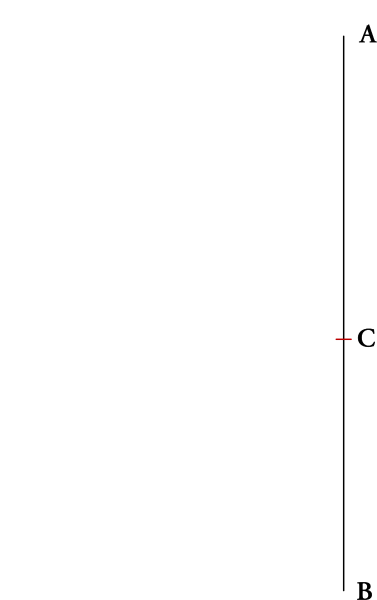

A – F

A to F is 4 3/4 graduated inches.

F – G

F to G is halfway between F and D, or 7 1/2 graduated inches from point A.

A – H

Square across from point A to point H, which is a total of 5 3/4 graduated inches. This gives us the shoulder point.

D – I

Square across D – I, at 10 5/8 graduated inches. This gives the width of the chest.

F – J

Square out from F to J at 10 graduated inches. This gives us the position of the neck point.

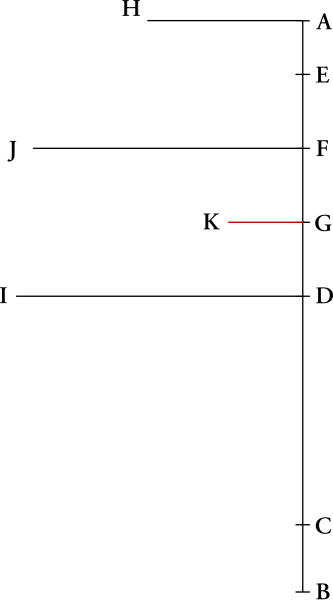

G – K

Square out from G to K, at 2 3/4 graduated inches. This gives us the width of the armscye.

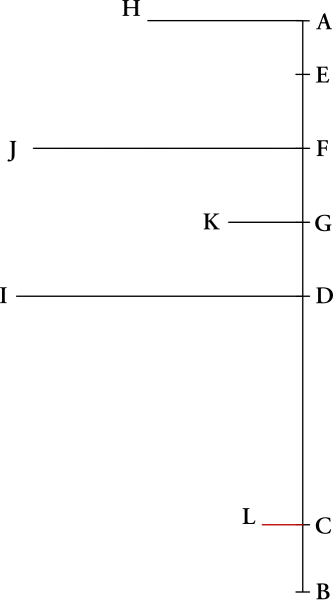

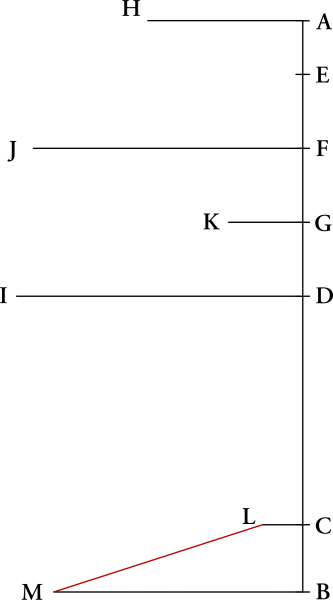

C – L

Square from C to L at 1 1/2 graduated inches.

L – M

Now we must find the center front of the waist. To do this, first draw an unmeasured line squared out from point B. The line just needs to be long enough for the next step.

Then measuring from point L, using 1/4″ of your full waist measurement, locate point M where the measurement intersects with the previous construction line.

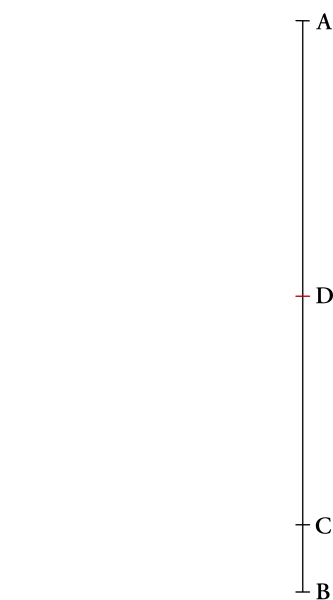

The Curves

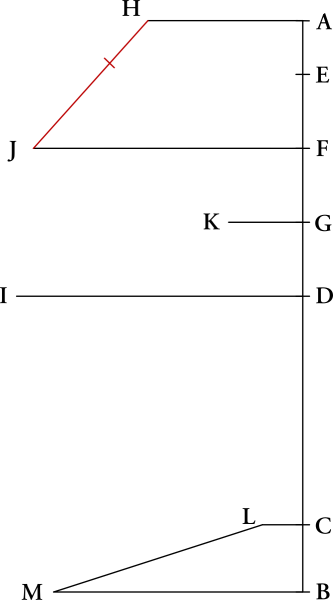

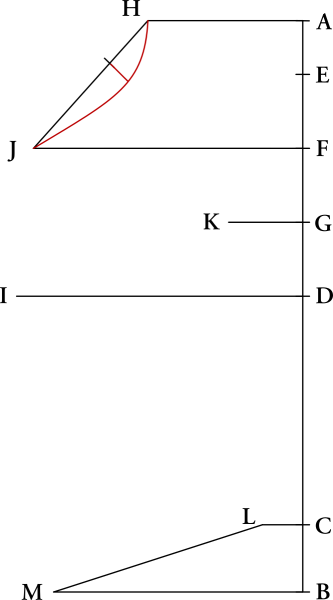

The Neck

Draw a line connecting points H and L. At one third of the way from point H, make a mark.

Square out from that mark 1 graduated inch. Connect the three points in a graceful curve as shown, giving us the line for the neck.

The Shoulder

Make a construction line from point H to E. At the midpoint, square out a line 1/4 graduated inches, and draw the curve as shown.

The Armscye

Draw a line from point E to K, and find the midpoint. Square in 3/8 graduated inches.

Do the same for the bottom of the scye, connecting point K to D. Square out from the midpoint 7/8 graduated inches.

Connect points E, K, and D in a graceful curve.

Side Seam

For the side seam, draw a straight construction line from point D to L. Then draw a slightly curved line as shown, hollowing 1/4 graduated inches a little above point L.

The Center Front

Draw to construction lines from point J to I to M. Then add a slight curve to the center front, using the construction lines as a guide.

The Waist

This is optional, but you can give additional shape to the waist as shown. If you can make the bottom front at point M be closer to a right angle, it’ll look a lot better in front rather than having a pointed look.

Your Progress

[columns gutter=”0″]

[col]

1 | Draft the front. |

[/col]

[col align_text=”center, middle”]

[/col]

[/columns]

Devere’s Drafting Formula

One of the more difficult concepts to understand is how Devere varied the size of a pattern. He used a size 18 3/4 breast as the basis for all of his patterns, which is equivalent to a 37 1/2 chest. This is called the proportionate model. If you are lucky enough to have a 37 1/2 chest (and the other corresponding measurements are the same), you can draft the patterns as they are straight from the book, with a normal ruler . Unfortunately, very few people fit these measurements, so adjustments have to be made.

Let us suppose we have a gentleman with a 42 inch chest, and want to find the correct balance for a coat. On a 37 1/2 inch proportionate model, the balance is 2 1/2. But a 42 inch chest would make that larger. First, you need to find the correct ratio between the 42 inch chest, and the proportionate chest. That would look like this:

42 / 37.5 = 1.12

After getting the number of 1.12, we multiply that by the balance measurement (or whatever measurement we need to get):

1.12 * 2.5 = 2.8

Then, it’s a matter of converting that 2.8 decimal into inches. This comes out to somewhere between 2 3/4 and 2 7/8. As you can see, this method is not very accurate, and prone to mathematical errors. And it takes a long time when you have to do 20 or 30 measurements this way.

Luckily, Devere was a fairly smart guy. He devised a set of rulers, called Graduated Rulers. The graduated rulers are, “a series of measures, which are successively graduated larger and smaller than the common inch measure, and are used to draft patterns for larger or smaller sizes than the 18 3/4 breast.” What does this mean? Instead of doing those calculations above, you simply choose a correct sized ruler and then draft the pattern as it is in the book.

When drafting trousers, the ruler size is taken from your seat measurement, rather than the chest.

Devere’s Graduated Rulers

For example, you are measuring someone and they have a 48 inch chest. You would then go to your set of rulers and choose the one marked size 48 (or 24 inch breast). If you compared this to a normal inch ruler, you would see that it is a lot larger, yet it still has 12 inches to it.

Where can you get these rulers? In Devere’s time, these rulers could be obtained from Devere’s company, and came on paper, tapes, or on wooden rulers. Devere has long gone out of business, but luckily, the rulers are not too difficult to make yourself. I’ll save you that trouble though.

I have created a set of graduated rulers, sized 34 through 50, for your convenience. They are on 11 x 17 inch paper, so you’ll need to find a print shop to print these. They can usually be printed for a few dollars on nice card stock at stores with print shops such as Staples. They are in Adobe pdf format. When printing from Adobe Acrobat Reader or other readers, be absolutely sure to set Page Scaling to None. If this is not done, your whole set of rulers will be off. After they are printed, I would take a normal inch ruler and compare it to the size 37 1/2 graduated ruler. They should be exactly the same. If they are off, it was printed incorrectly, and you’ll need to check your settings and try again.

Your Progress

[columns gutter=”0″]

[col]

1 | Read more about Devere's system. |

[/col]

[col align_text=”center, middle”]

[/col]

[/columns]

Waistcoat Measurements

This is an introductory course on drafting and constructing a period waistcoat circa 1860 – 1865. As it is intended as for the beginner, I’m leaving out a lot of the more technical information, which can be found in my frock coat drafting class.

Before we can begin drafting our waistcoat pattern, it is necessary to take a few measurements to ensure a good period fit. While a few of the measurements will seem familiar to you, Devere uses some special measurements based on the ‘center point’, which forms the basis for the entire system. Just take things step by step, feel free to ask questions in the forums, and I know you will get it.

To start off, here is an overview of all of the measurements Devere suggests, although the Front Opening measurement is not illustrated. Try to get someone to measure you. While it is possible to measure yourself (I do it all the time), it takes practice and skill, and it’s very difficult if you’ve never used these measurements before.

As you go, write down each measurement in the spreadsheet provided. You can either draft using the measurements that are filled out for you in the spreadsheet, or use the instructions found on the website, which use the graduated measure. You can download both below.

[callout]

- Graduated Rulers

- Measurements Spreadsheet (Libre Office)

- Measurements Spreadsheet (Microsoft Office)

[/callout]

All measurements should be taken over a well-fitted waistcoat, if possible. If you don’t have one, a period shirt will do.

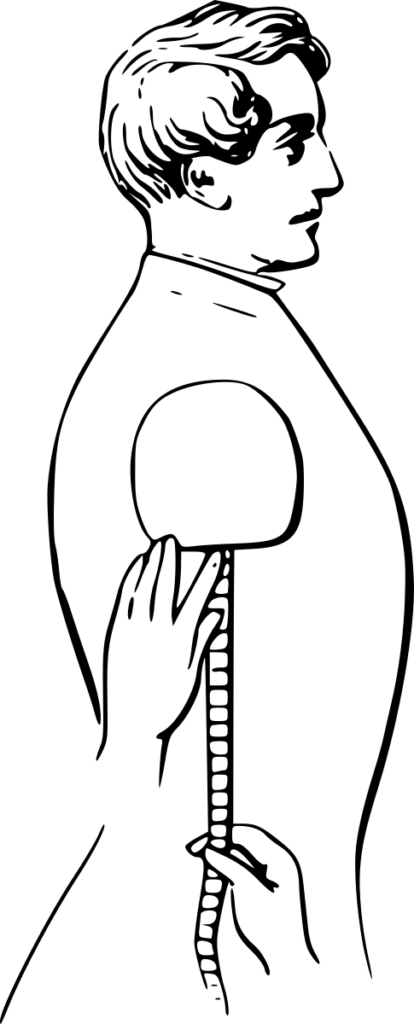

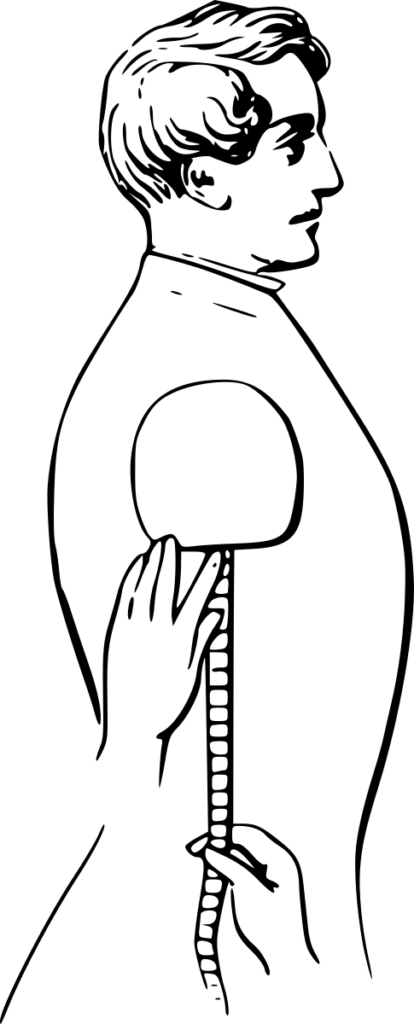

Breast

This measurement determines the size of the graduated measure you should use. Hold the tape around the chest as shown, as high as possible under the arms, and over the fullest part of the chest, holding the tape with the thumb and forefinger of each hand. Draw the tape very tight, and loosen it gently as the client breathes, for the best accuracy. Write this measurement down as half in the chart, i.e. if you have a 48 inch chest, write down 24 in the spreadsheet, since we only draft half of the waistcoat.Waist

This measure it goes around the body on a level with the hollow above the hips, and it should be taken rather easy. Like the breast measure, it is only written down as half the length taken; say 15 ¾ for 31 ½ inches.

This measure, by comparison with the breast, shows if the waist is thin or stout. In the proportionate man it is 15 ¾ or 3 less than the breast.

Waist

This measure is also taken under the coat: it goes round the body on a level with the hollow above the hips, see figure blank, and it should be taken rather easy. Like the breast measure, it is only written down as half the length taken; say 15 ¾ for 31 ½ inches.

This measure, by comparison with the breast, shows if the waist is thin or stout. In the proportionate man it is 15 ¾ or 3 less than the breast.

Finding the Centre Point

The center point forms the basis of finding the next two measurements, and lays out the position of the side seam. Unless you know you have a very accurate waistcoat (which you could use the side seam as the center point), it’s best to manually find the center point.

To find the centre point, we must use the formula of taking 2/5 of the Breast or 1/5 of the full chest and using that number to find the centre point. For example, a 35 inch chest measured all the way around would be 7 inches to the centre point. So find the center of the back at the waist level and measure 7 inches around to find the Centre Point. Or just fill out the spreadsheet and find the center point position that way.

Mark this center point on the client being measured using some chalk in the form of a cross hair +.

Curve

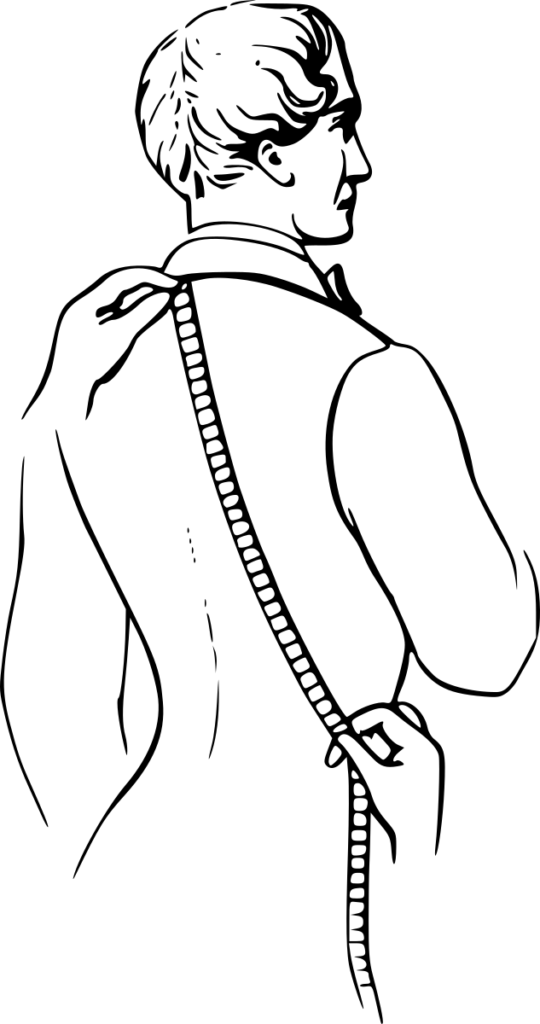

Take the Bust and Curve part of the Tape, slip the eyelet-hole at the end of it over the head of the pin, and hold it there; the eyelet-hole must be exactly at the top of the back seam: then with the other hand carry the tape perfectly straight to the Centre Point, crossing the side seam near the middle, and not letting the tape be either very tight or too slack.

Bust

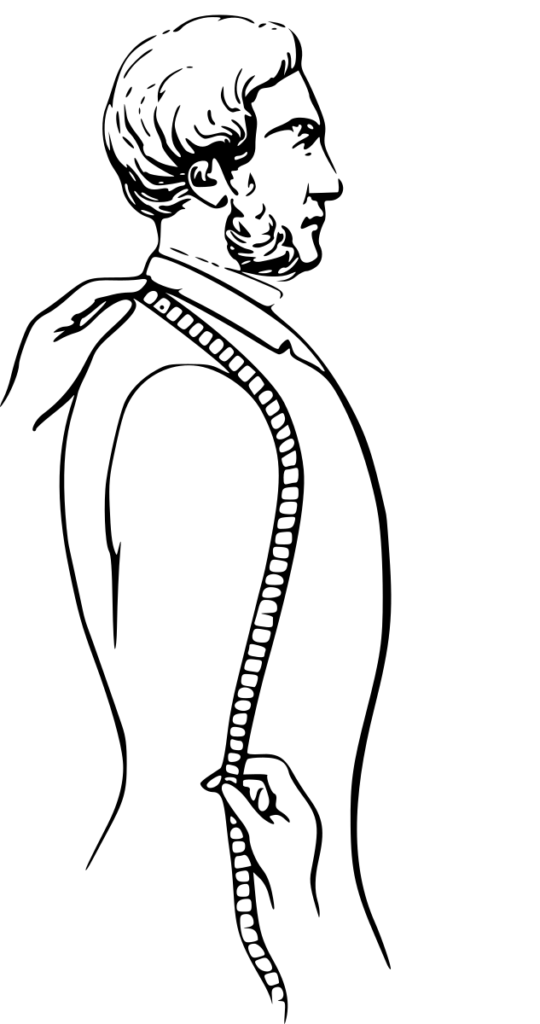

Continue to hold the end of the tape at the top of back seam, and with the other hand pass the tape over the shoulder in front of the arm, close to the front of the scye, letting the clients arm hang down in its natural position; draw the tape very tight, to flatten any creases there may be at the front of arm, and carry it direct to the Centre Point.

Side

Pass a pencil or penholder through the loop at the end of tape, and hold it tight under the arm (the arm must not be raised up, but should lay close to the body). Then measure the length to the Centre Point, so as to ascertain exactly, the distance between this point and the bottom of scye.

This measure serves to rule the depth of the bottom of scye, and shows the degree in which it must be hollowed out below the side point. In proportionate men it is 8 ½, and is usuallyabout half the length of back to natural waist. It is longer for extra erect men, and for small or high shoulders; and less for stooping men, and for large or low shoulders.

Opening

This is also known as the length of neck seam, and begins at the middle of the back neck and ends at the top of the desired opening in the front, being sure not to measure too tightly or loosely. This is a good measurement to use if you are copying a known vest or style and want the opening at a certain position.

Front Length

The Front Length is measured from the center of the back neck to the bottom of the front, and gives us a reliable way of checking that the length of the vest is correct.

Your Progress

[columns gutter=”0″]

[col]

1 | Take your measurements for the waistcoat. |

[/col]

[col align_text=”center, middle”]

[/col]

[/columns]