Category: Tailoring Basics

Cutting

Coming soon.

Laying Out the Patterns

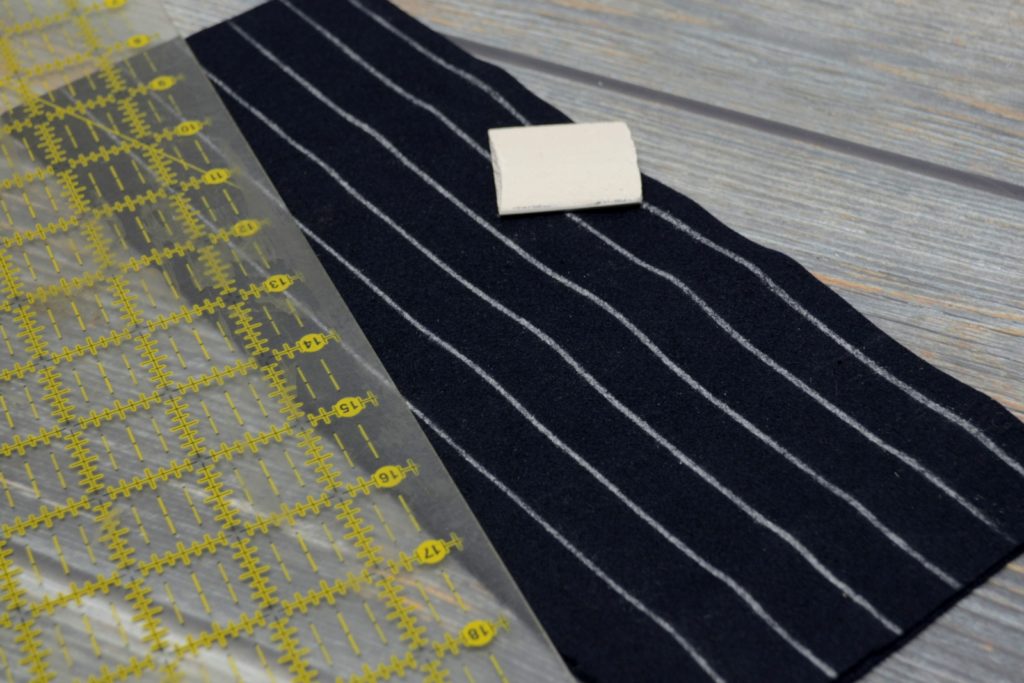

For most of the exercises in this tutorial, we’ll be using rectangular squares of fabric with which to practice the various stitches.

Using a quilting ruler or something similar, lay out a rectangle on your fabric parallel to the edge, or grain of the fabric. This should be roughly 5″ wide, in order to get some practice sewing on harder to reach areas, and 12″ long, which will allow you to time how long it takes to sew a foot. Then you can estimate sewing times for future projects more easily.

Note that in the following examples, I’m using a lighter-weight linen and a heavy wool to demonstrate the stitches to aid in contrast and allow you to see things better. You should try to practice on as wide a variety of fabrics as you can.

Next, cut out the pieces carefully using a pair of sharp scissors or shears. When cutting, the tip of the scissors, and the bottom of the handle should ideally always be touching the table.

Cut just on the inside of the line for best accuracy. Since the chalk has a width to it, cutting outside the lines would make the pattern piece too large, leading to errors when working on more involved projects.

Finally, mark parallel lines spaced 1/2″ or so apart along the length of the fabric. While the chalk lines are fine for practicing the basting stitches, I actually prefer to use a pencil if possible for this step for greater accuracy.

Here’s a video showing the entire process.

Tailor’s Chalk

A good tailor’s chalk in black and white is essential for laying out and marking your patterns on the cloth. I highly recommend avoiding those chalks that contain wax in their ingredients, as the wax will melt into the fabric when pressing and ruin the fabric. Instead, find on that is made of clay, and that will brush out when you’re done.

I’ve used Jems Clay Chalk for years and find it to work beautifully, but there are probably other varieties out there. A box will last for a very long time.

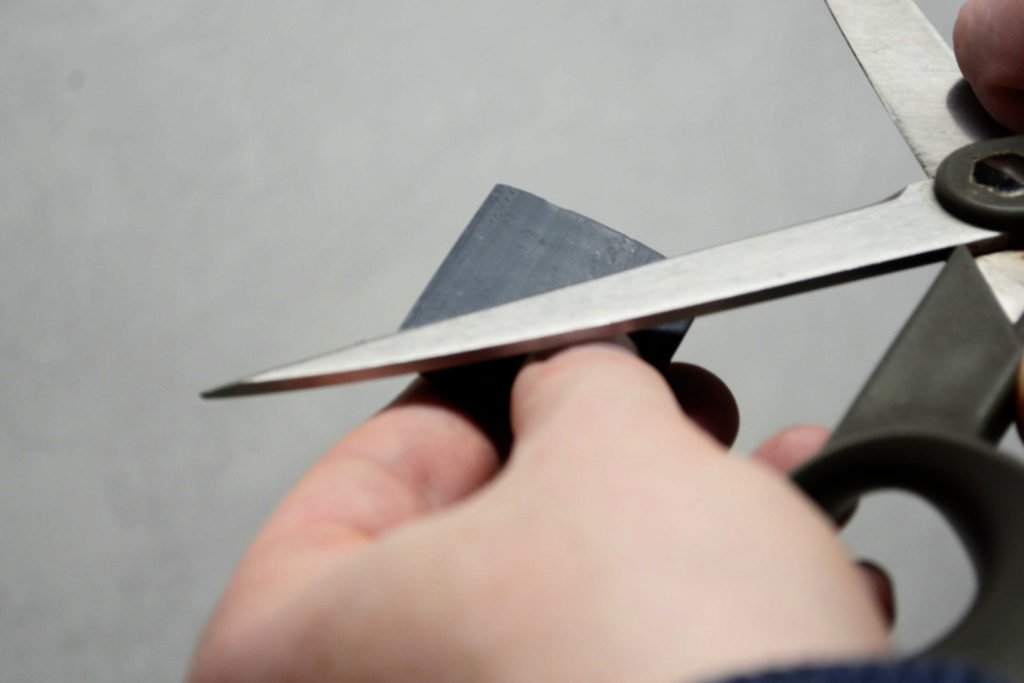

Before you use the chalk, you’ll want to sharpen it to get the most accurate line. There are sharpeners available, but I find them to be slow and don’t really sharpen the chalk all that well. Instead (and this will be heresy to some!), I use my fabric scissors to sharpen the chalk from both sides. Probably not the best idea as it does dull the scissors after a while, so you need to either use an old pair of scissors or be prepared to sharpen your own.

A short video on how I sharpen my chalk.

Needle Selection

Choosing a sewing needle is somewhat of a personal preference, but here are some general tips. If you are new to handsewing, I suggest getting a pack of ‘sharps’ or ‘between’ needles (if you can find those), of various sizes so that you can better get a feel for what works for you.

Sharps are very easy to find, have a narrow profile and sharp, tapered tip, but the downside is they are prone to bending. Betweens (sometimes called Quilting Betweens) are a little thicker and more durable for heavy tailoring work.

For size, you’ll have to see what works best for you, but I generally use between a size 8 to 12 (the larger the number the smaller the needle). It just comes down to experience and preference. For basting however I do like a larger needle to get through all of the layers and to give me some leverage.

If you can find them or order online, I highly recommend the John James needles, as they seem to use a better quality steel that resists bending for longer. Other brands will work though, especially if you’re just getting started.

Finally, don’t forget to change your needle often. Depending on what I’m sewing, that might be every other day, or it could be only an hour before I need to switch if I’m sewing particularly heavy fabrics. A sharp needle makes a huge difference!

Fabric Preparation

Before cutting into your nice woolen or linen fabric, it’s important to prepare the fabric by pre-shrinking in order to avoid shrinkage later after you’ve completed your trousers. There are several different methods you could use, but I’m going to focus on the one that works best for me.

When fabric is woven, there is a certain amount of tension that is put on the yarns in order to keep everything running smoothly on the loom. Our goal is to relax those fibers, with a bit of steam, so that we are free to work on our project without worrying about things shrinking after they are finished.

Lay your fabric out on your work surface or ironing board. For now, I’m using a towel placed on top of my table as a temporary ironing station until I get something better built. The board is underneath to protect the unfinished plywood. As you can see I’m using a basic home iron with a separate spray bottle for more control of the steam.

The basic idea is to wet the fabric with the water bottle, just enough to create some steam with the iron. That steam is what will relax the fibers and help get out any wrinkles. As you’re ironing, try to move lengthwise along the fabric in order to prevent stretching the fabric out of shape. Here is a video illustrating the process.

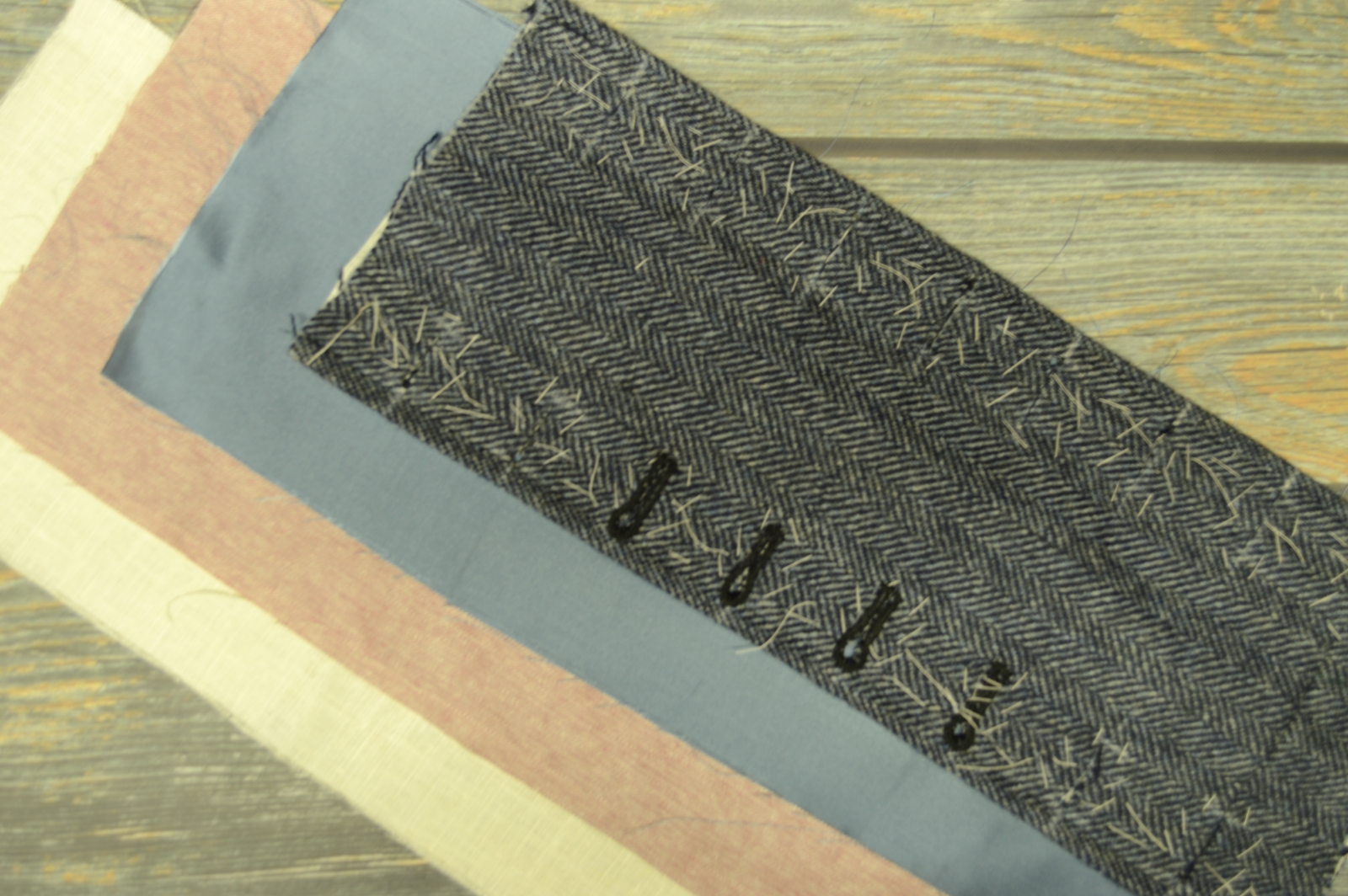

Fabric Selection

For this introductory class, I recommend practicing your stitches on as wide a variety of fabrics as you can. At many sewing stores, they usually have a ‘remnants’ bin where you can get smaller pieces of fabric from the end of bolts at a reduced price. For most of the exercises, I’ll be using a 5″ x 12″ piece of fabric, doubled, though you could vary the size to fit what you have.

Here are some fabric types to look for that are appropriate for the 19th century.

Wool

Wool was used in coats, waistcoats, and trousers and comes in a variety of weights, colors, patterns and weaves.

Linen

Linen comes in a variety of colors, from natural, white, red, green, blue, etc to black, and also in different patterns, such as stripes and plaids. I like to use a lightweight to medium weight linen for most of my projects, something about 4 – 6 ounces. Linen is great for summer wear, and was used in coats, trousers, and waistcoats.

Cotton

Cotton was used for linings, shirts, pocketing, and similar projects. Avoid solid colors, as the dyes back then would run in cottons. Small, repetitive prints are good, as well as woven designs such as seersucker and gingham.

Silk

For silk, look for either silk taffeta or brocade, especially those without slubs. Both are great for waistcoats, the taffeta could be used as a lining in a frock coat, though it’s a bit on the weaker side.

Thread Selection

Choosing appropriate thread for your hand-sewn historical projects can feel very intimidating at first. In this brief guide, I’ll recommend some thread to get started with, as well as the various types of thread I use on a day-to-day basis.

If you’re completely new to hand-sewing and intend to follow the lessons in this introductory course, I recommend starting with a cotton thread by Gutermann. It has the benefits of being on the more affordable side, while being easy to work with, especially if you wax and press it before using.

You’ll also want some cotton basting thread, which I’ll discuss more below.

It’s really a good idea to get experience with each of these threads as you can, so you can develop a feel for how each of them works and what you can use it for.

Polyester thread

Polyester thread is not used in historical tailoring, being a modern invention of the 20th century. But I definitely make use of it when sewing up muslin toiles and mock ups, as it is the most affordable of the various threads for the most part.

Linen Thread

Linen thread is among the oldest of the threads, with threads and fabric of linen being used since the time of ancient Egypt. It was used extensively at least in the 17th through 19th centuries, until cotton thread became more widely available. I tend to dislike linen thread due to past experiences with breaking and knots, so it’s very important to get a good quality thread and of course wax and press it before use. It could work well with linen coats and other clothing.

Cotton Thread

Cotton thread was first developed at the beginning of the 19th century and became more popular as the century went on. Most cotton thread today is mercerized, a process developed by John Mercer in 1844 and that didn’t come into common availability until the 1890s, which makes the cotton thread smoother, stronger, and better able to take dyes.

So the problem with cotton thread is that it’s very difficult to find unmercerized cotton thread as would have been common during the 1860s. There are pages upon pages of debates in various reenactment forums on whether or not to use cotton thread, and so these days I just stay out of the argument altogether. Use it if you wish, recognizing there is a slight difference from the originals.

I tend to use cotton thread on silks and linen garments for the main construction, as well as for the various cotton pieces such as pocketing, canvas construction, and so on, as the slightly weaker thread will break before the garment’s fabric will wear out, making for a relatively easy repair.

Silk Thread

Silk thread comes to us from China, with recorded usage of at least 5000 years. During the late Middle Ages and onwards it was brought to Europe via the silk road. I love using silk thread on my woolen garments, as the elasticity of the thread compliments the pliable hand of the wool, helping the various pieces to move more as one unit. I’ll also use it for top stitching on silk garments, but avoid it for main construction as it is strong enough to cut itself out of the seams.

Silk Buttonhole Twist

Buttonhole twist, although it can be found in polyester versions these days, was made from silk during the 19th century, and this is what I prefer for all of my buttonholes. It’s also great for attaching buttons and will hold easily for a decade or more of rough usage. The thread is produced in such a way that the thread will naturally want to form itself into a purl when working a buttonhole stitch. Cotton was also used for buttonholes but I’m not sure if it was made in the same twist pattern.

Cotton Basting Thread

Probably the most important thread on this page is the lowly cotton basting thread. This thread is slightly thicker and has a finish such that the cotton fibers help to grab onto the material to hold it into place while sewing. This is definitely something you’ll use everyday. Pictured is the five-mile-long spool I bought in April, 2009. It definitely lasts a while.

Waxing and Pressing Your Thread

Have you ever been plagued with knots or fraying threads while doing some hand sewing work? It can be a most frustrating event to be in the middle of a line of stitching and suddenly have the thread break off. For many years now I’ve been not only waxing, but pressing my sewing thread as well, with great results. It may seem crazy at first, but it’s completely worth the effort.

Start by cutting several strands of thread about 20 to 24 inches in length. By keeping the threads on the shorter side, you further decrease the likelihood of the thread fraying because you use up the thread before that can happen.

Next, rub the threads one at a time over a cake of beeswax. I’ve even used beeswax candles if I can’t find my little cake for some reason. I like to coat each strand twice in the beeswax to ensure even coverage. While you’re doing this, plug in your iron and let it heat up.

After all of the threads are coated, iron each piece, ensuring all of the wax melts into the thread. You can use a piece of paper to keep your ironing board wax free, or perhaps use a spare or old sleeve board like I do that you don’t mind getting dirty with wax and pigment / fiber buildup.

Your threads are ready to use now! I like to store them in groups of ten or twelve which I prepare each day before starting the next phase of my project. It’s tempting to do more sometimes but then they have a tendency to become tangled no matter how carefully you store them. If you compare the treated threads to some normal thread, you should find it has a much fuller body to it, and when used, these threads will go through even the toughest fabrics like butter. It truly is amazing and worth the five minutes of preparation it takes.

Here’s a video I prepared on the subject showing how to do each step. If you give it a try, please let me know in the comments how it works for you!

Using a Tailor’s Thimble

We all must have that one friend, or perhaps it is our self that is guilty, who insists upon sewing without the use of any thimble. I will admit I was one of them when I first started sewing more seriously, and was so proud of the callous on the tip of my finger that could drive the needle through two or three layers with no problem. As one becomes more serious in his or her tailoring work, however, it becomes clear that a thimble is most necessary if you want to progress in your skills and proficiency. And more specifically, a tailor’s thimble will best help you develop and refine your hand sewing.

Why a Tailor’s thimble?

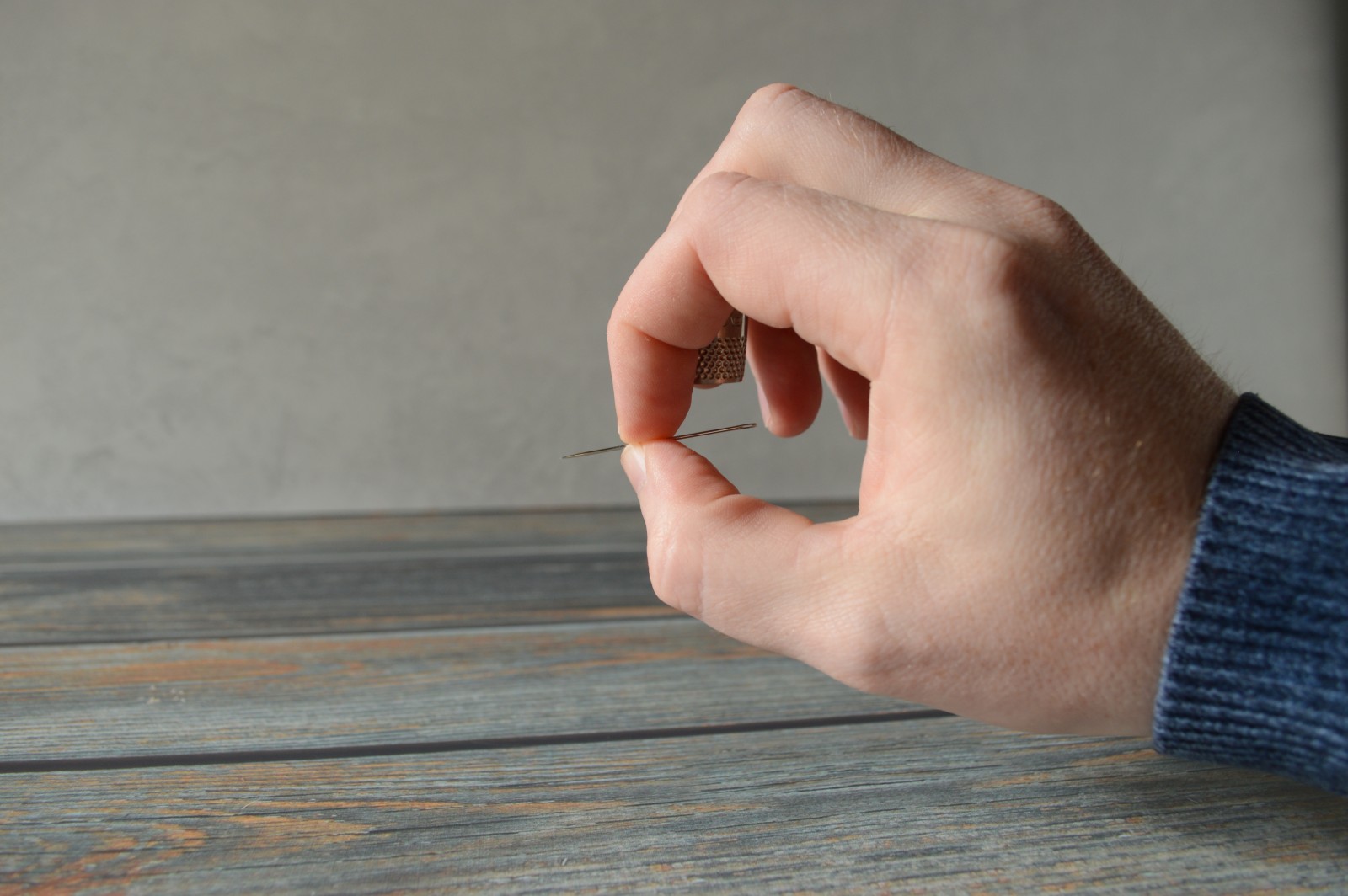

You may be used to a normal metal thimble often used by seamstresses and home sewers, that has the closed top. A tailor’s thimble, however, has an open top, and coming from a home sewing technique, they can seem intimidating, and indeed, you may have to alter your entire sewing technique.

Tailor’s thimbles have an open top for two important reason. First, they allow the tailor to sew for long periods of time without condensation forming in the tip of the finger under the thimble. Second, and most importantly, the open top gives the dexterity and tactility necessary for a tailor. As one is sewing, the fabric is constantly manipulated with both hands, and having that open top allows you to use the tip of that covered finger to aid in this manipulation.

Choosing the right size

Choosing a thimble can be a bit of a challenge these days. Unless you have a higher end sewing store nearby that carries tailor’s thimbles, you’ll probably have to order them online and guess at the sizing. I found mine at B. Black and Sons, and since I have medium to large hands, I bought both a size 9 and 10. After some use, I found that the size 10 was a better fit for me, so you may have to order a couple different sizes and experiment for yourself.

When determining a good fit, place the thimble on your middle finger of your dominant hand. The tip of your finger should extend past the top of the thimble by about 1/16 to 1/8 of an inch, allowing you to get a feel for the fabric as you are sewing. If the thimble is too small, your finger will not protrude enough and you’ll lose that sense of touch in that finger. Too big and the thimble will tend to slide around or even fall off.

Another point to keep in mind is the material of the thimble. Most of the new thimbles for sale today are made out of some kind of nickle alloy and for certain people this can give a slight allergic reaction. The only solution I can think of is to hunt down an antique thimble made out of sterling silver or find that rare source for a new one. Be prepared to spend a lot more money, though.

How to use the thimble

The first thing to remember when using a thimble is to always stay completely relaxed. The moment you start to tense up the muscles in your fingers, hand, wrist, or arm, you’ll begin losing a degree of control over your work and you will tire out more quickly.

Hold the thimble on the middle finger on your dominant hand, and just let your fingers relax into a very loose fist, as pictured.

If necessary, you can try tying a piece of ribbon or string around the thimble and your finger in order to keep the thimble in the correct position. After a few days to a week you should be able to do without it. Remember to stay relaxed!

Rotate your hand, forearm, elbow and even your shoulder all as one unit, keeping your fingers in the same position. The fingers actually move very little while sewing. The larger muscles of your arms will propel the needle through the fabric, while your fingers will subtly manipulate the needle to position it perfectly for the next stitch.

Practice this rotational movement for a bit. You can work on it each day for about two to five minutes, just like any other exercise. When you are comfortable with the motions, start to pretend you are holding the needle between your thumb and index finger and continue doing these movements.

One very important thing to avoid is bending your wrist either up or down, or two the side. You need to keep it aligned with your forearm in order to prevent such things as tendonitis and carpal tunnel syndrome.

Finally, you are ready to try using the thimble with a needle. Start by placing the middle of the needle between your thumb and index finger. The eye end of the needle is placed on the thimble at a point above your finger nail. This is contrary to what a lot of home sewers and quilters do, so it may take getting used to. With that rotational movement, push the needle firmly through the fabric and up again all in one stroke.

You’ll find that the movement does not need to be as exaggerated as in the exercises you worked on, but the rotation is definitely still there. Remember to remain relaxed at all times!

Another subtle point to keep in mind is that as the needle passes to the bottom side of the fabric, it should actually touch the index finger of your opposite hand in order to help you gauge the depth and length of your stitch. It should be just a light touch or prick, and you’ll quickly build up a callous on the tip of that finger. By doing this, you avoid having to look at the under side of your work with every stitch. It’s very exaggerated in the photo for clarity, but in reality it’s barely seen or felt.

After you are comfortable passing the needle through the fabric, you can start using your fingers more to control the point of the needle more precisely. The point between the thumb and index finger acts as a fulcrum point while the middle finger and thimble subtly move the needle as necessary.

Here’s a video demonstrating all of the above points. As with anything, it takes a bit of time and practice to get used to using the tailor’s thimble. Another thing that might help you speed up the process is to wear the thimble around the house as you go about your day. You’ll find you can do just about anything while wearing it, even typing, which helps to build your dexterity.

Hopefully this short introduction to the tailor’s thimble helps you with your sewing. Have you used a thimble in the past? Was the technique similar? Share your thoughts and comments below!