Category: Drafting Frock Coats of the 1860s

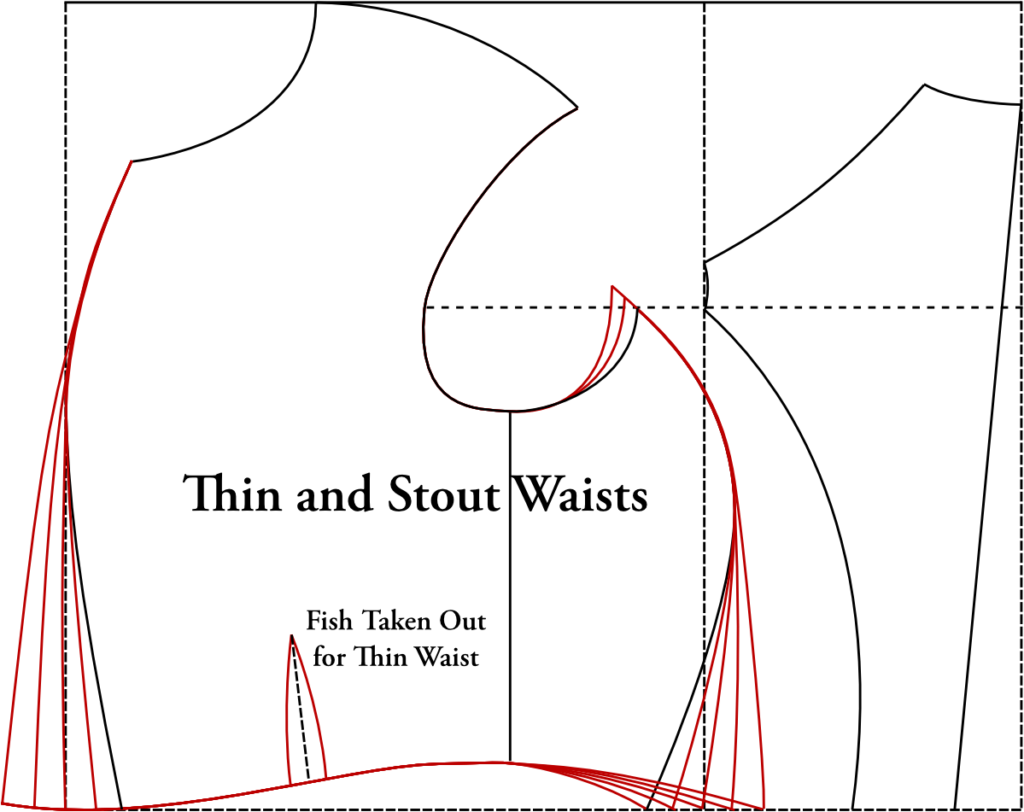

Thin and Stout Waists

Adjusting for thin or stout waists is one of the most common alterations I come across. It’s so easy to make the pattern a little tight across the waist, for example.

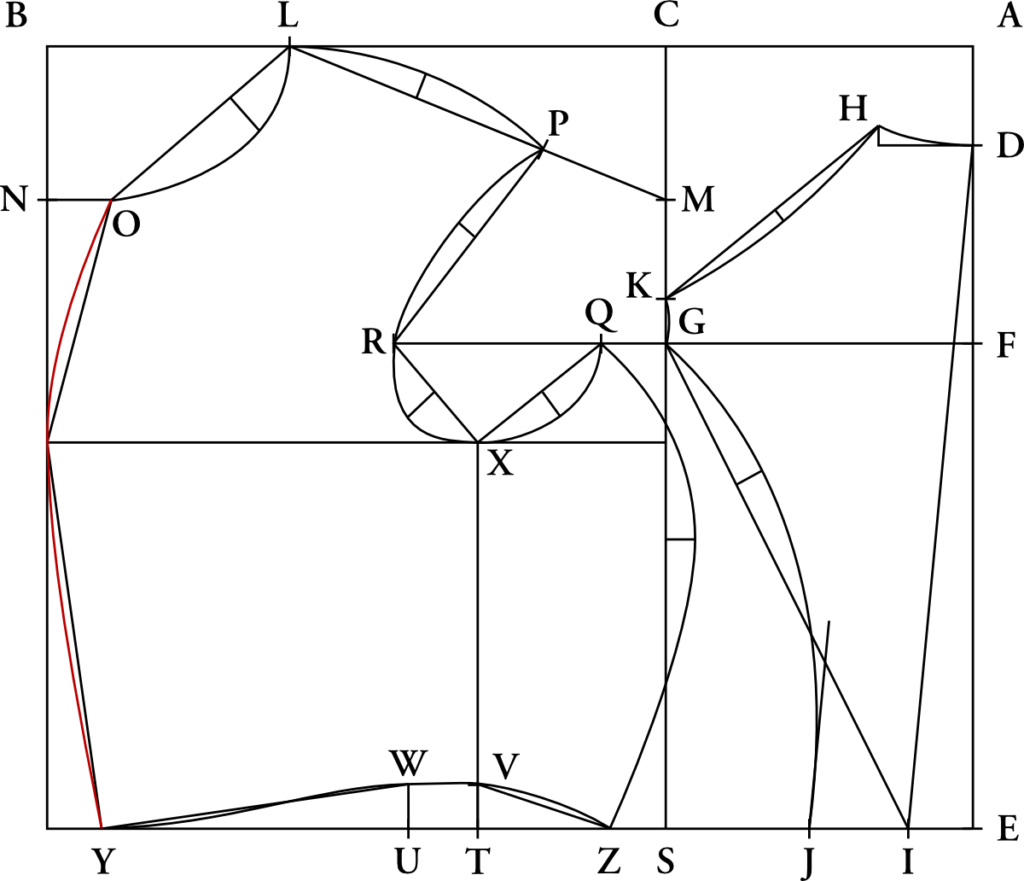

In the proportionate man, the waist is 3 less than the breast—if the difference is more than this, the waist is thin; if less, it is stout. For the thin waist, the front edge and side seams are drawn as for the proportionate structure, and the waist is diminished as required, by taking out a fish in the waist seam. If the waist is stout, it is drafted correct at once, by giving half the measure in front and half the back, starting from the middle of waist. For Very Stout waists the side point must be raised up and also advanced a little, as shown in this diagram.

Balance

Balance is the most critical aspects of a good fitting coat. Have you ever noticed that the majority of reproduction coats fall away at the front? This is due to defects in the balance, which is affected by both the cut, the ironwork done (or not done) and the construction process. Balance is the difference between the relative lengths of back and forepart, and is ruled by the difference which exists between the measures of bust and curve.

Stooping and Erect

For the stooping man, fig 2, the difference between the measures of Bust and Curve, becomes less than for the proportionate structure, and this difference being placed at the corner ofthe square, causes the back to be much longer in comparison to the forepart. Besides this the chest will become flatter, and the side seam of forepart rounder; which alterations are made by the the supplementary measures.

N.B. In cases where the man is very stooping, we may also take the shoulder point a little forward, never more than 3/8, and lower the neck seam a little, as shown by the interrupted line on fig. 2. This will improve the fit for these extreme cases, from the manner in which the straight cut in the forepart requires making up.

For the Extra-Erect man, the back becomes shorter compared with the forepart, because the balance or difference between the measures of Bust and Curve, is more for than the Proportionate Structure. The supplementary measures also cause the chest to be made rounder, and the side seam plainer.

For Extremely Erect men, we may assist the fit, by taking back the shoulder piece and raising the neck seam a little – see the dotted line. But these variations in the place of the shoulder point, should only be made in extreme cases, and should never exceed 3/8 of an inch.

As a general rule in drafting for the Stooping and Extra erect structures, we may say: make the chest flatter and the side seams rounder for stooping men, and give more round to the chest and less to the side seam of forepart, for Extra erect ones. This may be carried out in a slight degree for those builds, even when the supplementary measures have not been taken.”

Louis Devere

In Practice

When checking for this on your toile, check the back of the neck. If you see folds of fabric at the back of the neck, you drafted with too much back balance. Take a pin and pin out the folds you see, and measure the amount that is pinned. Then take that amount and deduct it on your draft as shown.

If there is no extra fabric, but a gap shows at the back of the neck, then you drafted for too erect a figure. Measure the distance it is off, and add that to the draft as shown.

In both cases, this is due to being inaccurate when taking your bust and curve measurements. In time you will become more accurate, and be able to compensate as you draft.

Use of the Supplementary Measures

Now that you’ve completed the close fitting wrapper, it is now time to try it on and check for fitting issues. Throughout this section, we will go into detail with each problem you may encounter along the way.

You will learn how to adapt your pattern to some of the variations encountered in the human body. With experience, you’ll learn how to read the body, and anticipate the changes needed while you draft. While learning however, it’s best to take things step by step. I suggest reading through, and noting which problems you can see on your draft as you find them.

Use of the Supplementary Measures

If you have had any misfits while trying on the close fitting wrapper, the first step you should take is to use the supplementary measures to check your draft, and correct when necessary. If the measurements are within half an inch of the draft you made, I recommend leaving the draft as it is, and correcting during the fittings if necessary.

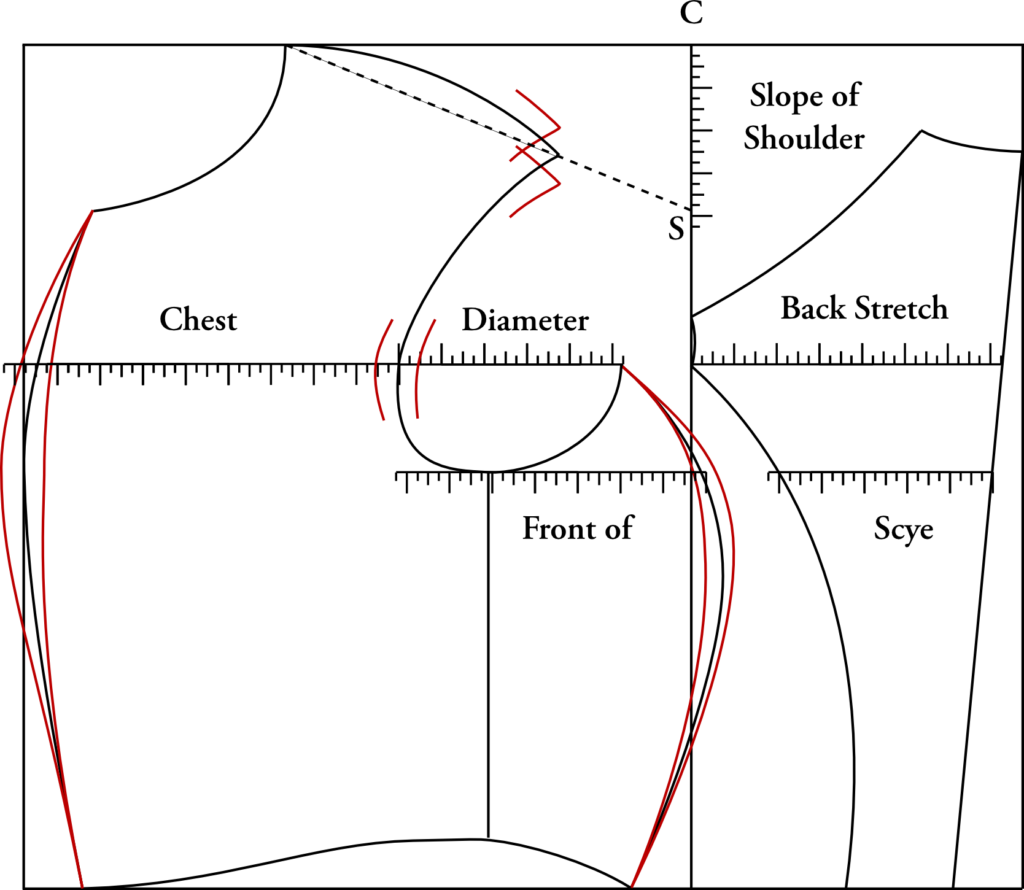

Back Stretch

Apply the measure of Back Stretch to see if this part requires widening or narrowing, which will very rarely be the case.

I always check this measurement, just to make sure I’m in the ballpark with the width of the back. One common mistake in reproductions is to see a back that is too wide, with folds of fabric forming over the shoulders at the back.

Diameter

Starting from the side point, apply the measure of Diameter, and take the front of scye forward or backward if required.

This measurement checks that the armscye is the correct diameter for the arm. If your client has built up muscles from exercising, for example, this will need to be checked.

Front of Scye

If the measure of Front of Scye is more than the Back Stretch and Diameter added together, give more round to the side seam of the forepart. If the Front of Scye measures less than these two measures, give less round to the side seam.

This combined with the previous measurement is a way of checking the armscye position, since two measurements are used. This measure is useful if your client complains that the armscye is too tight in the front. You may see a fold of fabric at the front of scye, and this will help get rid of that. Make sure you perform the ironwork first before correcting this, however, as the ironwork affects the fit of the armscye.

Chest

Starting from the front of scye at its corrected place, apply the width of Chest; and make the front edge rounder or flatter if required.

You will have noticed the roundness of the chest while drafting – while that is very good, too much or too little roundness will make the ironwork very difficult to perform.

Slope of Shoulder

Correct the slope of shoulder, by marking downwards from C to S, double the length of the Slope measure, so as to make the shoulder seam more sloping for low shoulders, and less sloping for high shoulders.

Many people have a dropped shoulder on one side or the other. If this is the case, you will need to apply this measurement, ending up with two different patterns for the right and left sides. It’s a bit more work, but worth the effort.

After the pattern has been corrected, it will be as accurate as possible, and will have every point subject to variation positioned according to your custom measurements. We have now to show how this system of drafting adapts itself, without any trouble or difficulty, to all the changes of conformation which are met with in the human body. We shall therefore take each structure separately, and show how the application of the measures, causes the alterations in the pattern required for each build.

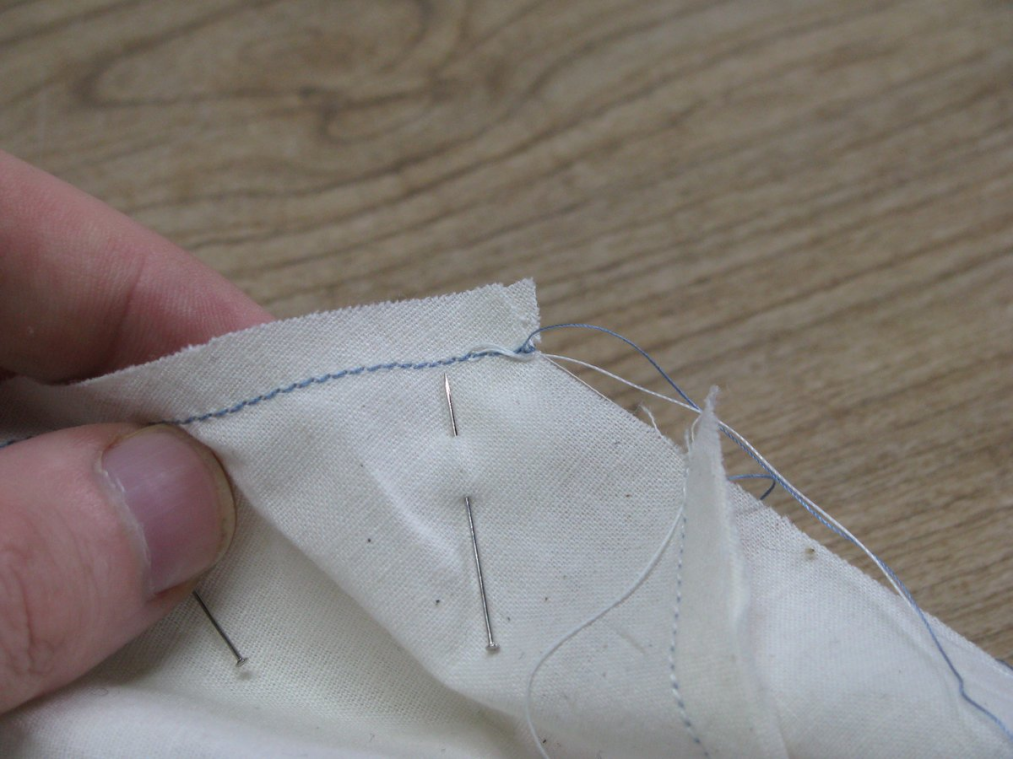

Constructing the Toile

Take up the side pieces, and lay them on top of the fronts, lining up the side seams as shown. About the only time I use pins is in constructing the toile, so you may pin these pieces together as shown.

Make sure right sides are together. The X’s should be on the outside. Sew the seam, and press open afterwards.

Next, with right sides together, line up the side piece with the back piece. This is a complicated seam to line up properly. At the points where G and Q are from the draft, the side piece should extend the length of the seam allowance, 1⁄4 inch. At the bottom, the side piece should be 1⁄4 to 1⁄2 inches below the end of the curved back seam. Pin these two points together. Then starting from the top, ease the two layers together, pinning as you go.

It’s a little tricky at first, but that’s why we’re practicing. Then carefully sew this seam, with the side seam down. When sewing, the fullest side of the fabric should always be facing down. Carefully arrange the curved seam over a tailor’s ham, and lightly press. When that’s done, line up the shoulder seams, again, right sides together. You’ll notice that the back is a little wider than the front. This gives a little ease for the shoulder blades. You should pin the ends, then pin the middle, and then add two more pins in between, for a total of five pins. Ease the fabric in as you go, then carefully sew the pieces together.

Note in the close up photo how the edge of the fabric is offset. This is so the seam allowances meet at the appropriate spot, 1⁄4 inch in from both.

Finally, take both halves of the wrapper and pin them along the center back seam, right sides together, and sew.

You have now completed your toile. Please try it on and take photos from the front, back, and side, and post them on the forum for a critique of the fit.

Ironwork

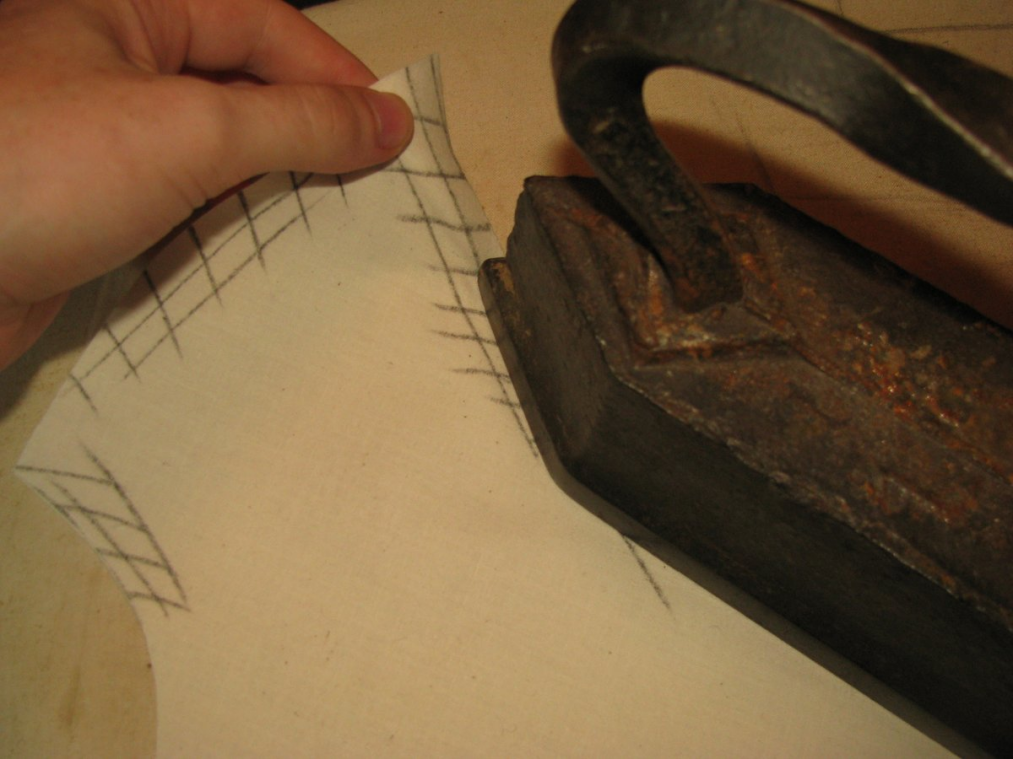

Before you do any sewing, you must do a little ironwork. Ironwork involves stretching or fulling (shrinking) the fabric in certain areas, and is part of what sets tailoring apart from other methods of sewing, such as dress making. We will go into more detail of this when we do the ironwork on the actual wool, but for now, just follow along.

The areas to stretch are marked in the photo with hash marks. We will refrain from any fulling for now, as cotton does not shrink well with the iron. When stretching, both pieces of fabric should be together, so as to ensure the pieces are stretched the same amount. When stretching the cotton muslin, don’t pull too hard. A very slight pressure is all that is necessary.

Begin with stretching the armscye, about 3⁄4 of an inch. Hold the fabric by the shoulder point and pull the fabric with the iron. Next, give a good stretch to the top of the shoulder seam, about 1⁄2 inch total. Finally, carefully stretch the neck starting just at the hollow near the top.

The results are shown in the following photograph. You can see a convex shape has been formed over the shoulder and scye.

This ironwork has the effect of helping impart shape into your garment, as well as helping to provide a better fit. Linen and cotton are not workable with the iron, however, so we will be learning how to take that into account.

Striking the Pattern

After the pieces are cut out, it’s time to lay them out on your muslin fabric.

Make sure the fabric is smooth and free of wrinkles, and that the selvage edges are aligned, or at least parallel. The fabric should be doubled, not in a single layer. You will cut through two layers at once. Place each pattern piece on the fabric, being sure to align the plumb lines on each with the warp, or lengthwise grain. This helps the garment to hang properly.

Instead of using pins to hold the pattern pieces in place, you should use pattern weights of some kind. While these are available for sale, I find it easier to use what I have around. Rulers, scissors, books and other heavy items are perfect for this. Then take your black tailors chalk, making sure it is sharp (a pair of old scissors is good), carefully trace around the pattern with a think chalk line. Mark an X on each piece of fabric, so you can figure out which is the right side later on.

When every piece has been traced, it is time to cut. When cutting, you should cut on the inside of the chalk mark, as the chalk adds a bit of width, which would throw off the fit. Do not snip the scissors entirely closed as you cut, rather cut until the scissors are only near the end. This helps you to cut a nice clean line.

After cutting, mark the other side with an X as well.

Seam Allowances

There are several schools of thought about Devere and seam allowances. Some add 1⁄2 an inch around every seam, except 1⁄4 for the armscye. The issue with this method is that it makes the coat much less fitted.

The other extreme is adding no seam allowances at all. I’ve tried this several times and have found that major adjustments were then needed for the pattern, as it had become too small.

Devere gives clues to his preferences on seam allowances. From his 1866 manual, he states:

“In cutting out the garments in the cloth, it must be borne in mind that the seams are not to be allowed for. All the allowances requisite for the various seams, are given to the pattern by our systems of drafting, without any calculation.”

However, in his 1856 manual, he has this to say about seam allowances:

“When using the measures to draft any pattern whatever, there are certain differences to be made in the measures according as the parts of the coat corresponding to each of them are stretched hard or taken in, and also if these parts must fit tight or loose. As a general rule, for woolen cloths we allow for the seams in the length of the cloth and not in the width, because cloth is nearly always elastic in the way of the woof, and often stretches more than is required for the seams.”

I generally follow his suggestions from the 1856 manual. I add seam allowances to the side seam, the curved seams, and the center back. I do not add a seam allowance at the shoulder seam, which I’ll explain in much greater detail in a later module.

To add the seam allowances, you’ll need your seam gauge. I like to line the seam up along the length of the ruler, using the slit in the middle for alignment. I then use the centimeter side to draw a seam allowance. It’s slightly less than 1⁄4 inch, but when you trace out the fabric with fabric, it ends up being just right.

Add 1/4 inch seam allowances to the following:

- Side Seam of Front

- Side Seam of Side Body

- Curved Seam of Side Side Body

- Curved Seam of Back

- Center Back

After you’ve added the seam allowances, you ma•y cut out each piece carefully, using paper scissors. Don’t use your good scissors or you will dull them!

Note that the seam allowance method given here is applicable to all types of frock coats, including those made of wool. By creating a base pattern like this, properly fitted, you will not be as limited in the future.

Transferring the Pattern

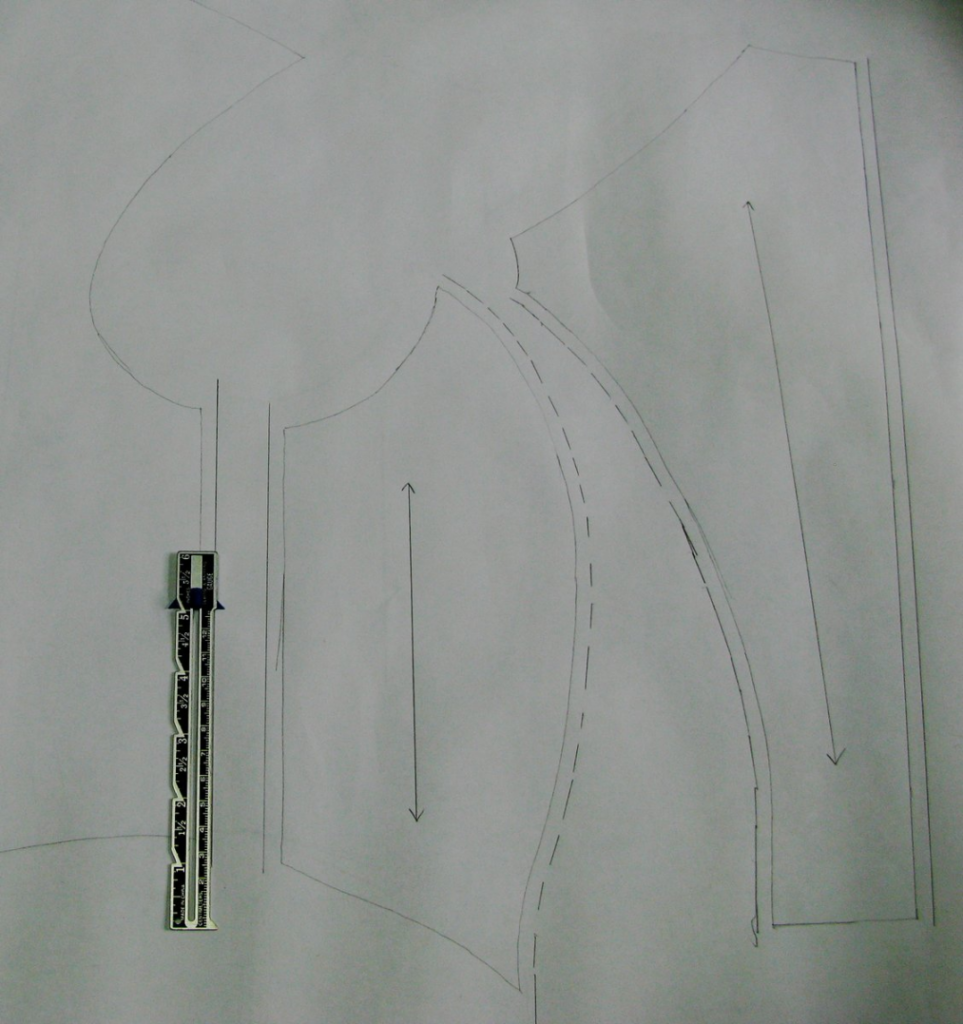

Going from a draft to a usable pattern is a relatively straightforward process. Notice there are three pieces to the pattern. The front and side pieces are separated by the line X – V, and of course the back. It is highly recommended to preserve this original draft, and make a copy to cut out for use in sewing.

There are two methods I’ve used for transferring the pattern to new paper. The first is to lay the draft onto a new sheet of pattern paper, and carefully run over the seams with a pattern tracing wheel. The spokes on the wheel will poke through to the new sheet of paper. At this point, you then connect the dots and you have your new pattern pieces.

Make sure that you separate the side and front pieces when you trace. Simply move the draft over a few inches after you’ve traced one piece, then trace the other. This is to give you space to draw in seam allowances.

Another method is to put the draft on the bottom, and the new sheet of paper on top. If your paper is on the thinner side, you can see through to the bottom, and simply trace the pattern out. You can also use a light table if you have one. This is actually my preferred method, but do what you are more comfortable with. Again, make sure the side and front pieces are separated before tracing.

Finalizing the Pattern

It is now time to begin the process of turning your draft into a wearable garment. In this module, you will learn how to add seam allowances, cut the pattern pieces, and cut out and construct the a toile for the upper body of the coat. This toile has two purposes: one is to check the pattern for fit before using your expensive fabrics; and two, to familiarize yourself with the proper frock coat body construction techniques.

Marking Up and Truing the Pattern

Before you transfer your pattern, there are several things you should do beforehand. The first is to mark the plumb line on each piece of the pattern. Simply draw a line parallel to your construction lines as shown. It may be helpful to add an arrows as a reminder to pay attention to them.

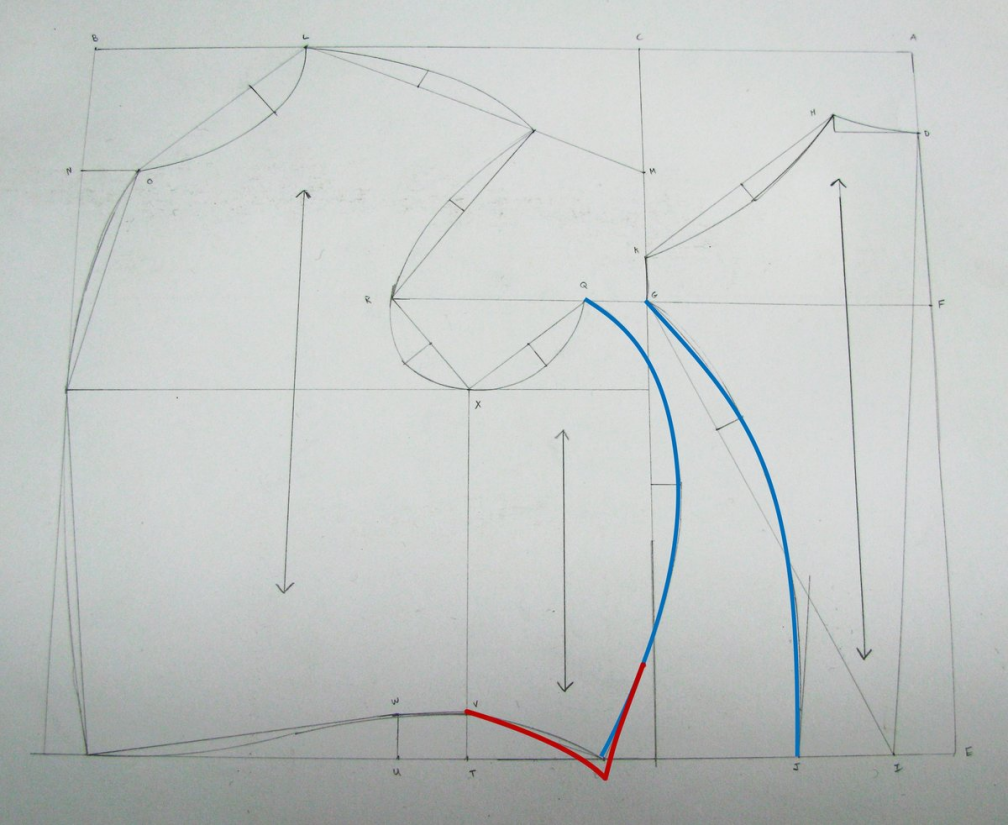

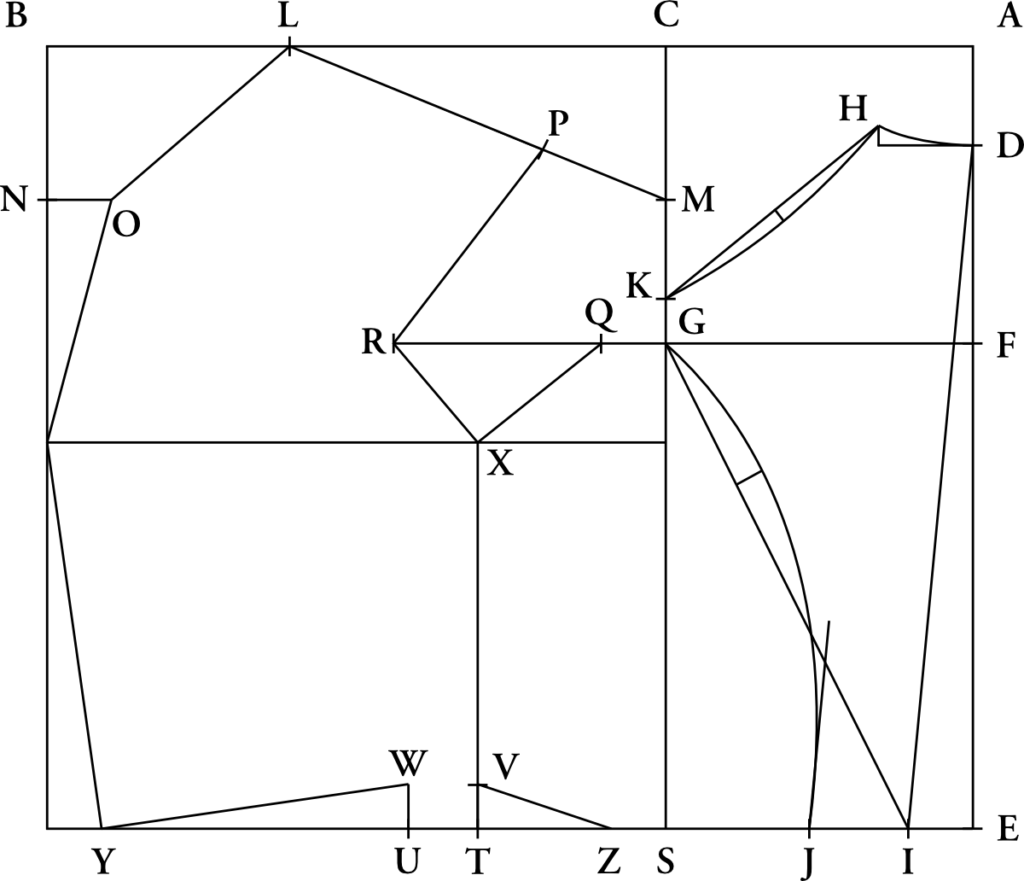

Next, you must measure the side seam of the back, and compare it to the curved seam of the side body,both shown in blue. The side piece should be about 1⁄4 to 1⁄2 inches longer than the back piece, for aid in construction. If you don’t ensure this, you will have problems putting the coat together later.

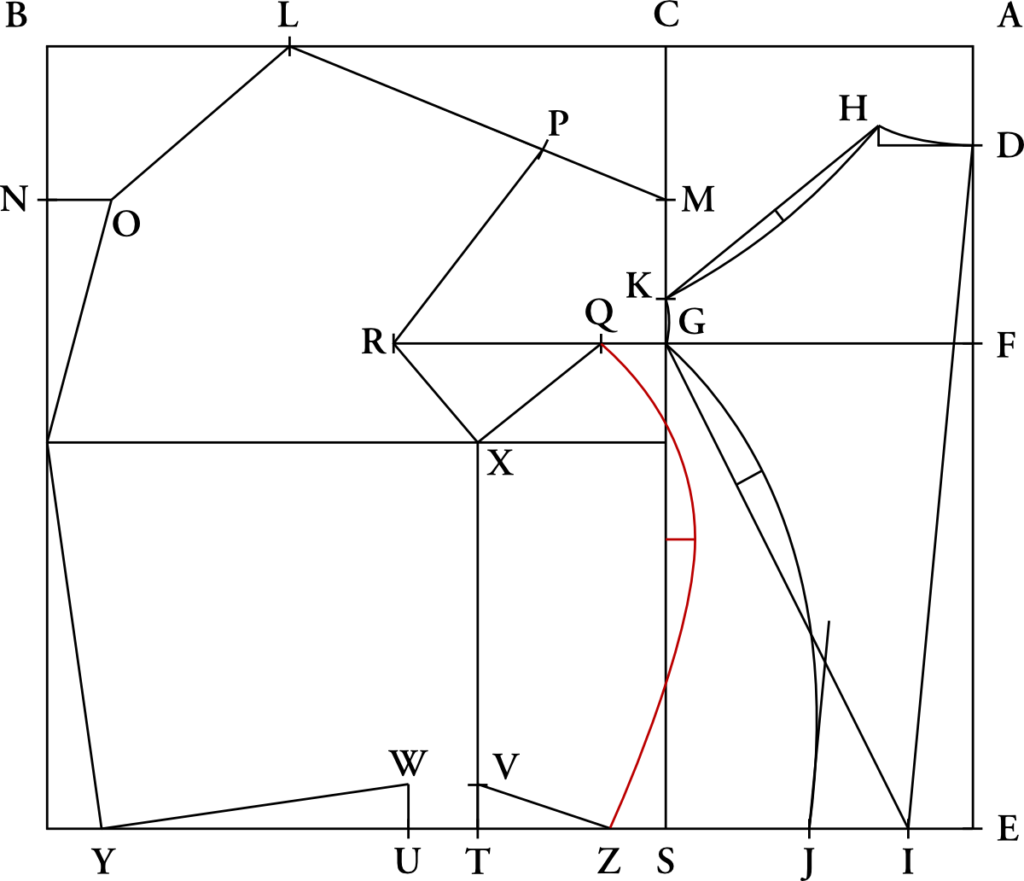

To do this, simply move the point Z down the specified amount, square with the bottom construction line, as shown in the red. Then redraw the bottom and curved seams of the side piece, as shown.

Now is also a good time to check the other seams for issues, for example comparing the width of the shoulder seams, or comparing various widths and lengths to your own measurements.

Adding the Curves

We’re almost done – it’s now time to draw the curves. I strongly advising using French curves for these, as you’ll get a more accurate and flowing line.

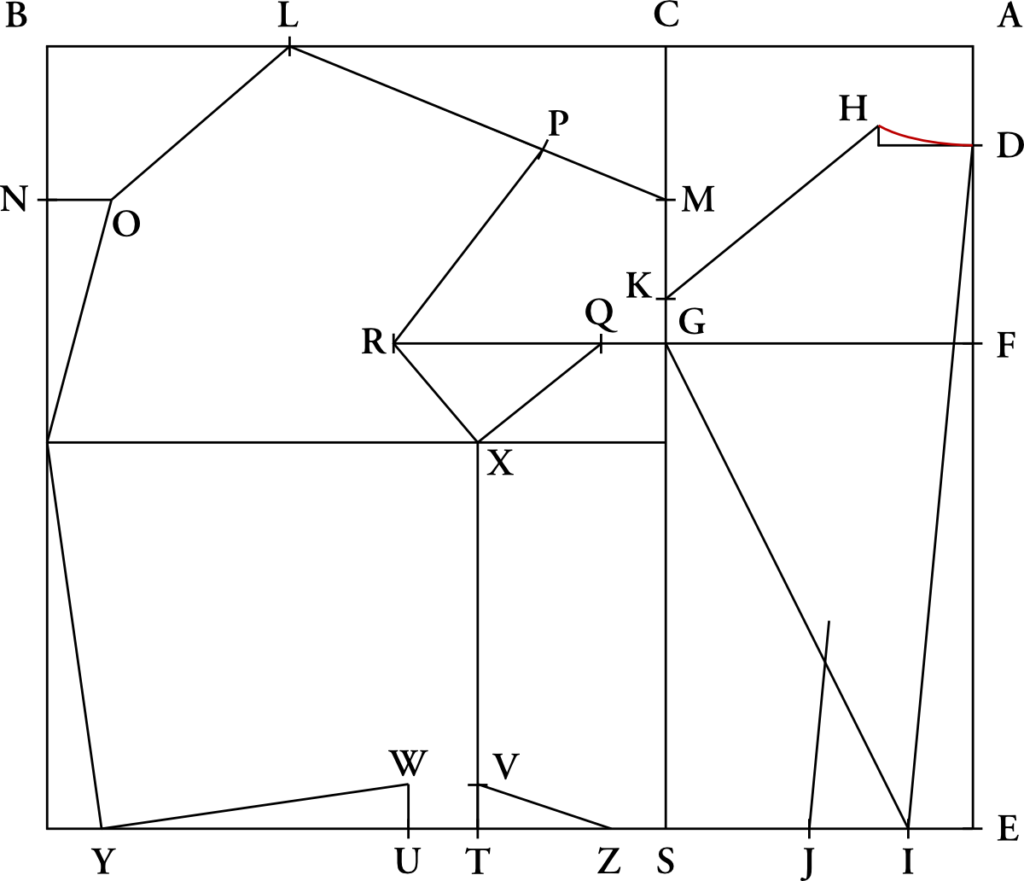

Back Neck

Draw a smooth curve connecting point H to Point D.

Shoulder Seam Hollow

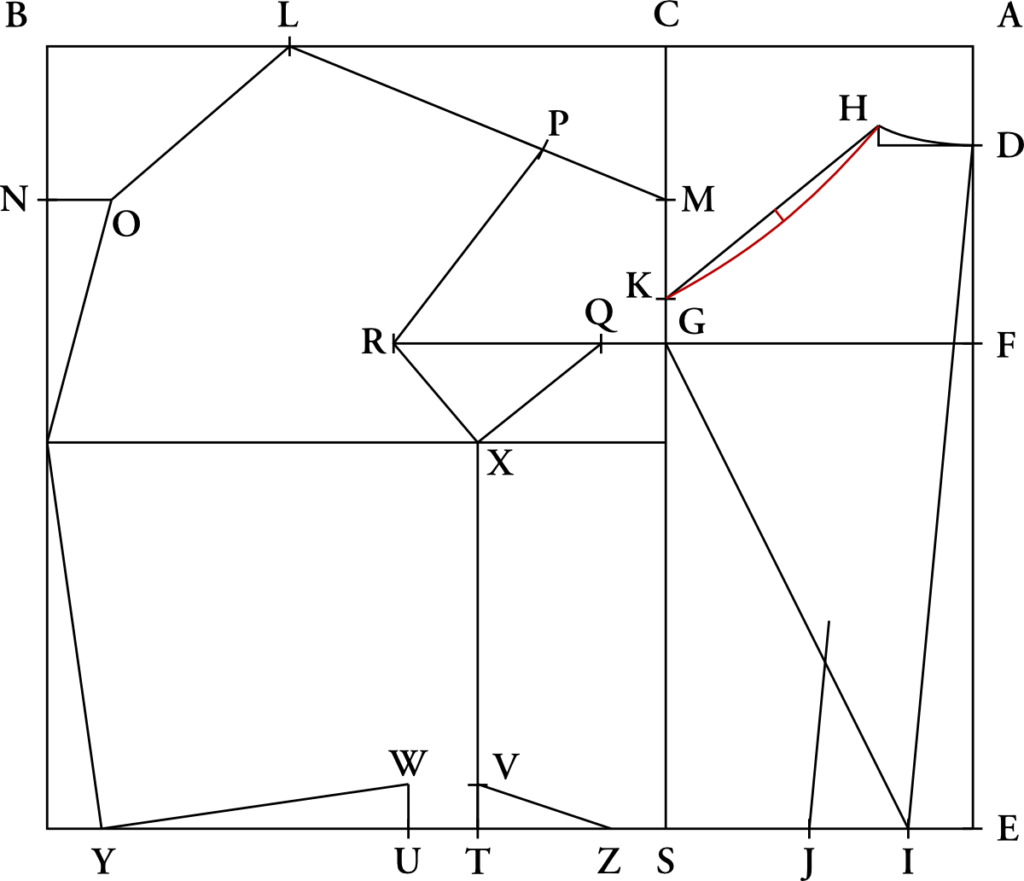

The following method is used to find most of the following curves. Start by measuring line H – K, and finding the center point. Next, square down 3/8 graduated inches. Finally, draw a nice curve connecting K to the point we just found, ending at point H.

Side Seam Hollowing

To find this curve, we must first measure 4 graduated inches on the oblique line from point G. At this point, square up 3/4 graduated inch. This is where the curve will have the greatest hollow.Draw a curve from point G, through the point you just found, to point J. The short construction line you made will aid in drawing the bottom half of the curve. The curved line should stay to the left of this line.

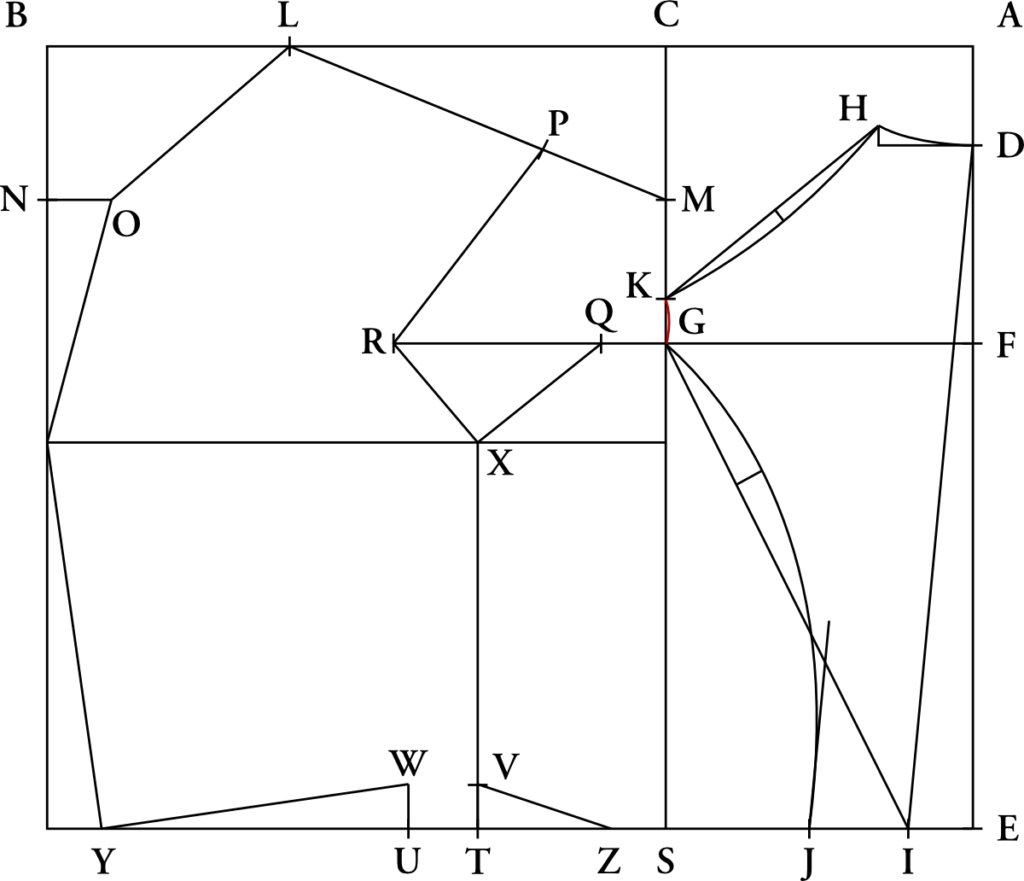

Back Armscye

From G to K, draw a slight curve. There are no straight lines on the human body, so adding the curve here makes this seam a little more harmonious.

Side Body Seam

I generally find this seam the trickiest to draw. Devere is vague about the exact placement. To begin, I measure down 5 graduated inches from point G, towards S, and square out 3/4 of a graduated inch.Draw the curve from point Q, through the point you just made, almost straightening out until you arrive at point Z. This curve should pass a little above the construction line from point X.Remember that a lot of these curves depend on your artistic sense, as well. They will not look exactly like this draft, as everyone has different measurements.

Shoulder Seam Roundness

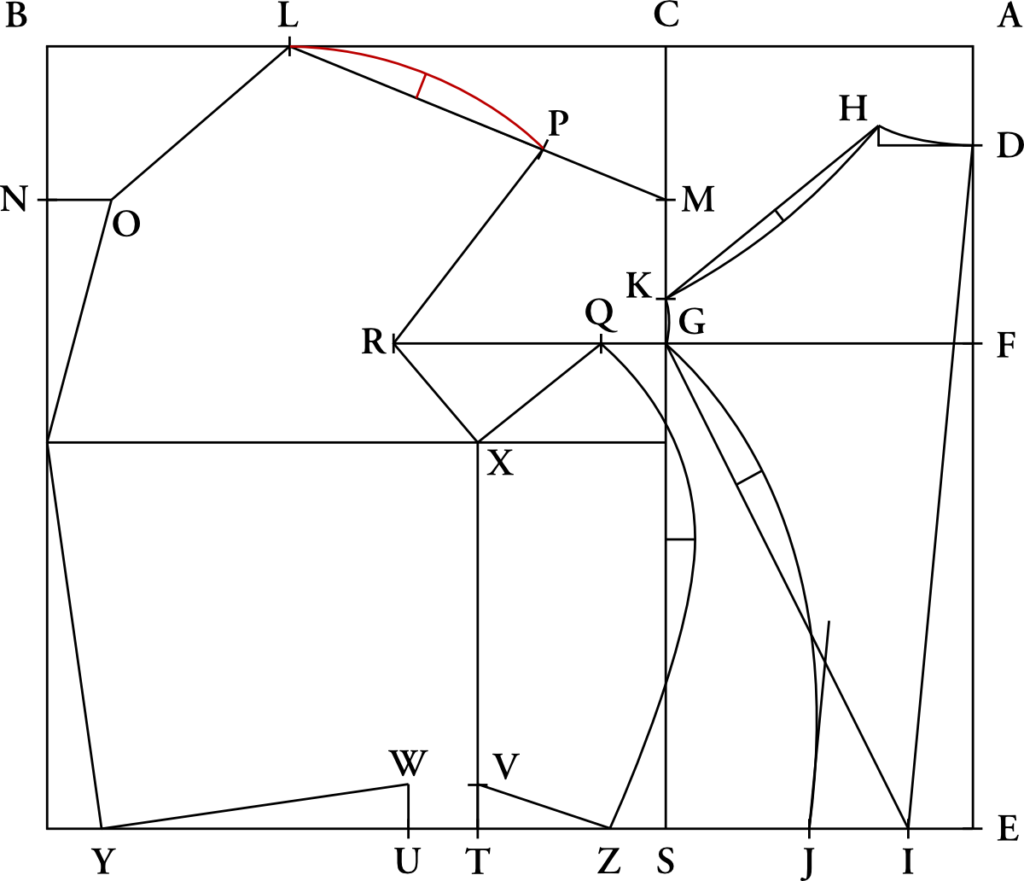

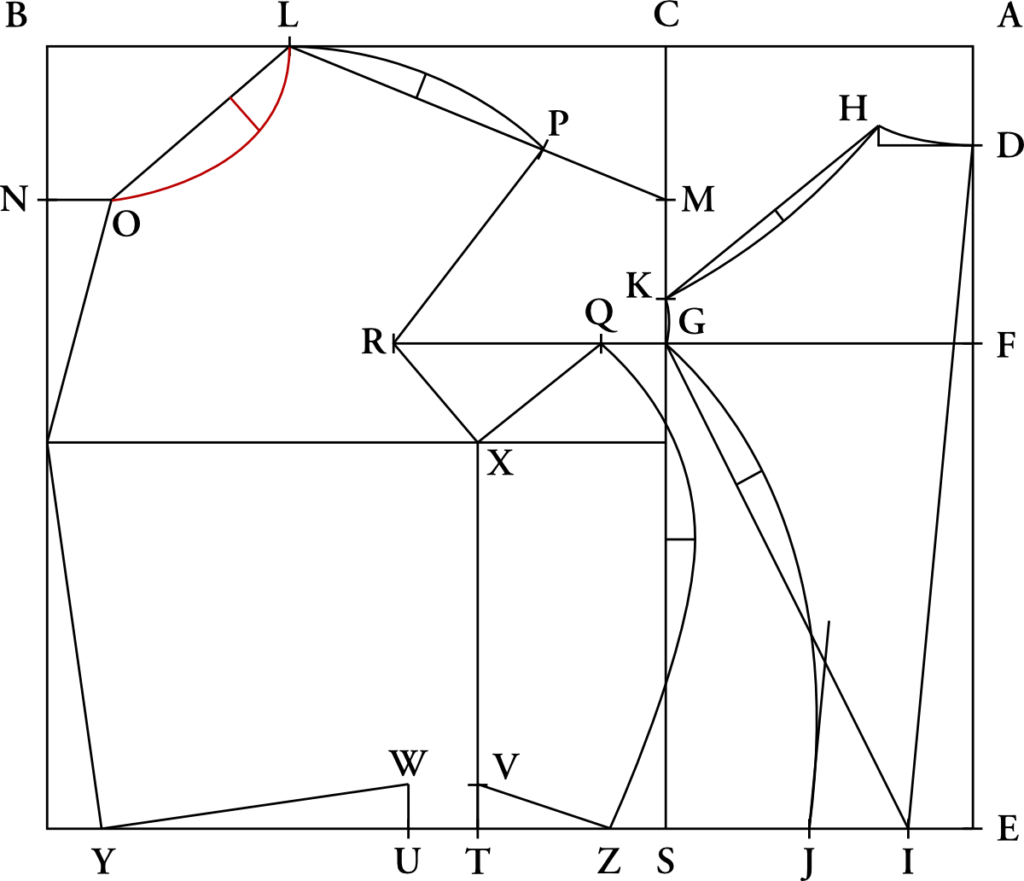

Find the center between points L and P, and square up 5/8 of a graduated inch.Draw the curve, connecting points L, the point you just drew, and point P.

Neck Curve

For the neck seam, divide the line from L to O into three parts (here is where the tailor’s square comes in handy). Starting from the shoulder, mark one third in, and square a line off from this point measuring 1 1/8 graduated inches in length. Draw the curve from point L, through this point, ending at point O.

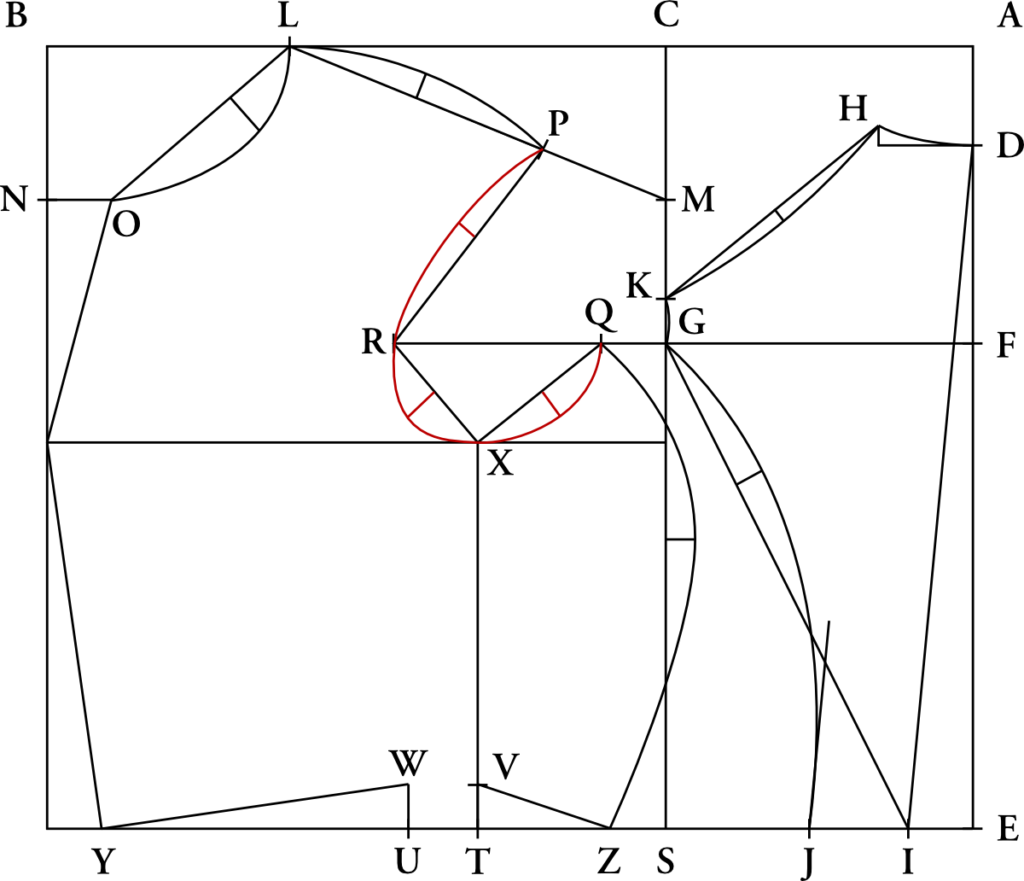

Armscye

We’ll combine the following three steps into one since you are hopefully catching on by now. At the Center of P – R, hollow in 1/2 graduated inch for the front of scye.

At the center of line R – X, hollow in 7/8 graduated inch for the bottom of scye.

At the center of line X – Q, hollow in 3/4 graduated inch for the rear bottom of scye. These curves should all flow harmoniously into each other, with nice smooth intersections.

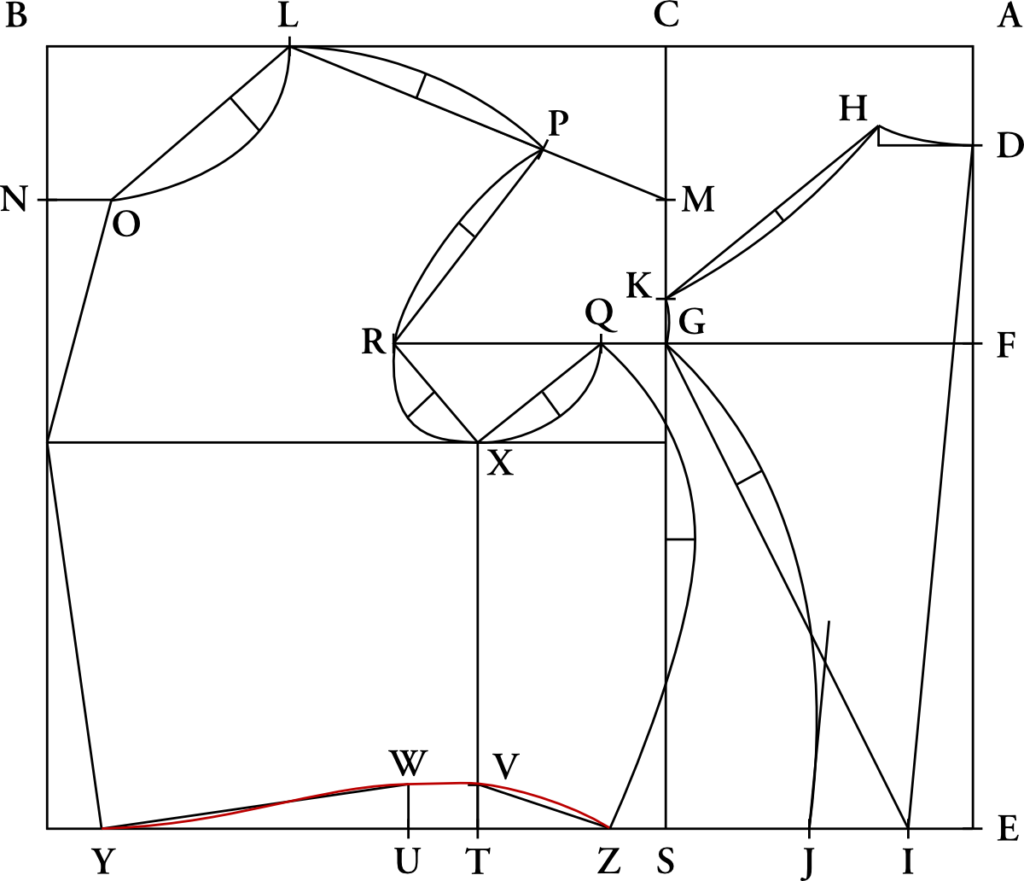

Waist Seam

At the bottom of the waist seam, connect points Y, W, V, and Z in a nice curve as shown. Study the larger size draft at the end for a clearer view. Note the hollowing of the waist at the side piece.

Center Front

Finally, draw a single curve connecting point O to the chest line from X, to Y at the waist line. A hip curve is very useful for this.

Congratulations, you have completed the draft for a close-fitting wrapper. Below is a diagram of the pattern edges. Seam allowances will be dealt with in the next module.

At this time, please post your draft on the forum, so we can discuss and figure out any problems you may be having. Next, we will begin constructing the muslin wrapper, and discussing the many fitting issues that can occur.