Author: James Williams

Devere’s Graduated Rulers

Devere realized this was a tedious way of drafting. Remember, they didn’t have computers or spreadsheets back then. Instead, Devere devised a set of rulers, called Graduated Rulers. The graduated rulers are, “a series of measures, which are successively graduated larger and smaller than the common inch measure, and are used to draft patterns for larger or smaller sizes than the 18 3/4 breast.” What does this mean? Instead of doing those calculations above, you simply choose a correct sized ruler and then draft the pattern as it is in the book.

For example, you are measuring someone and they have a 48 inch chest. You would then go to your set of rulers and choose the one marked size 48 (for a 24 inch breast). If you compared this to a normal inch ruler, you would see that it is a lot larger, yet it still has 12 inches to it.

Where can you get these rulers? In Devere’s time, Devere sold these rulers, for which you can find advertisements in his manual. They came on paper, tapes, or on wooden rulers. Devere has sadly long gone out of business, but luckily, the rulers are not too difficult to make yourself. I’ve saved you that trouble, though.

I have created a set of graduated rulers, sized 34 through 50, for your convenience. They are on 11 x 17 inch paper, so you’ll need to find a print shop to print these. They can usually be printed for a few dollars on nice card stock at stores with print shops such as Staples. They are in Adobe pdf format. When printing from Adobe Acrobat Reader or other readers, be absolutely sure to set Page Scaling to None. If this is not done, your whole set of rulers will be off. After they are printed, I would take a normal inch ruler and compare it to the size 37 1/2 graduated ruler. They should be exactly the same. If they are off, it was printed incorrectly, and you’ll need to check your settings and try again.

The nice thing about these rulers is that you perform absolutely no mathematical calculations, unlike the spreadsheet option. Just pick the ruler that corresponds to your chest size, and use that when drafting.

Since these will be printed on relatively flimsy paper, you should use a regular ruler or tailor’s square to draw your straight lines, and then measure off the distance with the graduated ruler.

Be mindful that not every step calls for a graduated ruler. If you used a graduated ruler for everything, you’ll simply end up with that proportionate draft that we want to avoid. Instead, when a Common Inch is called for, use a normal ruler. When the graduated inch is called for, use the graduated ruler in the size corresponding to your chest.

If you don’t find your sized ruler included, please let me know and I will make one up for you. If you are between sizes, round up to the nearest inch.

Devere’s Formula

One of the more difficult concepts to understand is how Devere varied the size of a pattern. He used a size 18 3/4 breast as the basis for all of his patterns (half of your chest measurement equals the breast measurement), which is equivalent to a 37 1/2 chest. This is called the proportionate model. If you are lucky enough to have a 37 1/2 chest (and the other corresponding measurements are the same), you can draft the patterns as they are straight from the book, with a normal ruler . Unfortunately, very few people fit these measurements, so adjustments have to be made.

Let us suppose we have a gentleman with a 42 inch chest, and want to find the correct balance. On a 37 1/2 inch proportionate model, the balance is 2 1/2. But a 42 inch chest would make that larger. First, you need to find the correct ratio between the 42 inch chest, and the proportionate chest. That would look like this:

42 / 37.5 = 1.12

This number is called the scale factor.

After getting this number, 1.12, we multiply that by the balance measurement (or whichever measurement we need to get):

1.12 * 2.5 = 2.8

Then, it’s a matter of converting that 2.8 decimal into inches. This comes out to somewhere between 2 3/4 and 2 7/8. A combined formula for finding these measurements is as follows:

x = the proportionate measure for which you wish to find the scaled measure.

M = Your whole chest measurement.

x * (M / 37.5) = scaled measurement

While possible to work out these calculations for each measurement in the draft, it is extremely time consuming and prone to error.

One tool to making this easier, is a spreadsheet, which you saw when you wrote down your measurements. On it, you’ll find a chart that’s automatically filled out with numbers as you type in your measurements. What is happening behind the scenes is that the spreadsheet program is calculating all of those measures to your breast size, automatically. To use this spreadsheet for drafting, simply plug in the numbers for each step as called for.

For example, if you are a chest size 40, when asked to draw the line from A to D, you would find that in the spreadsheet, and measure out 25 inches.

As you can see, all of the calculations are done for you and updated as you type in the measurements. If you wish to use the spreadsheet, I advise printing it out after you fill it in, so as not to accidentally change numbers while using it.

Devere’s System of Drafting

We will begin our draft for a frock coat by first drafting a close-fitting wrapper, out of muslin. This is simply a generic frock body, containing the front, side, and back pieces, and is used to work out major fitting issues before you cut out your expensive materials. This close-fitting wrapper is drafted without any fashion features, and is strictly for testing the fit of your coat.

The drafting techniques and wrapper you construct will be applicable to nearly any Civilian frock coat of the period. I advise you save your original pattern after the corrections have been made, as you will find it very useful if you wish to create other coats in the future.

Preparing your Workspace

You will find pattern drafting much more enjoyable if you have a comfortable space to work in. The most important issue is having enough space. You don’t want to have the edges of your pattern crammed up against a counter, or falling off a table, for example. Assuming you do not have a proper drafting table (even I don’t have one), a dining room table makes a perfect drafting surface. Just be careful of the cracks between the table leaves, as the pencil is prone to poking holes in the paper.

Also try to find a good chair. You’ll be sitting in one place for at least an hour, and you do not want to get a sore back. A computer chair can be quite comfortable, and you can swivel to get the best angle for drawing lines.

Lighting is also very important. If you can draft in an area with good sunlight, all the better. The worst situation for drafting is when shadows start forming on the draft, obscuring parts of your draft. Dining room lights are usually fairly bright, making this another good reason to draft at the dining room table.

Devere’s System of Drafting

Louis Devere created a wonderful drafting system, in that it’s fairly simple and accurate to use. In his drafting book, The Handbook of Practical Cutting on the Centre Point System, he laid out a system based on the size of your chest. And as you saw, many measurements started from the centre point on the waist, hence the name Centre Point System.

In the manual, you are instructed to create a proportionate draft, using a system of graduated rulers. For every person, the drafted numbers remain the same, you just change the size of the ruler. A larger person uses a larger ruler, a smaller person uses a smaller ruler.

There is just one problem with this, however. Very few people fit that ‘proportionate’ description. Here is how Devere describes the proportionate man.

“The Well Proportioned Man has his body of medium length, neither long nor short: he is neither thin nor stout at waist: his attitude is upright, neither stooping nor standing extra erect: his shoulders are of moderate size, and are neither high nor low.”

Louis Devere

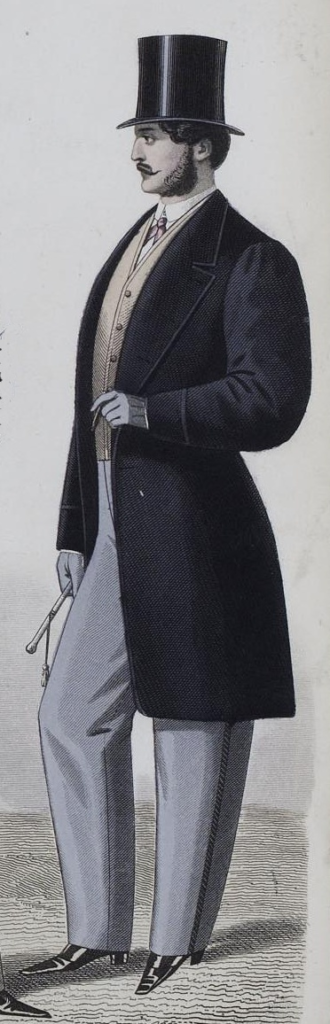

In actual terms of measurement, Devere’s proportionate figure had a 37.5 inch chest, a 31.5 inch waist, and although not actually stated, probably around a height of 5 feet 8 inches. Think of a young man in his early 20s, with an athletic build, at the pinnacle of physical fitness. This is what Devere’s proportionate man would have looked like.

Let’s assume we are drafting a coat for a large figure, with a 52 inch chest. If we were to use Devere’s proportionate draft, we would end up drafting a coat for someone that’s over 6 1⁄2 feet tall. It’s very rare to find someone that tall with a 52 inch chest.

As you can see, drafting by proportions alone is prone to issues. What is the solution? We use a combination of proportionate measurements, and direct measurements. For example, you’ll find the depth of the armscye with a proportion of the breast, while drafting the side measurement with your direct measurement. This will be made more clear when following the draft.

Measuring for a Coat

Before the first stitch is made, and before the drafting pencil ever touches the paper, measurements must be taken. When measuring, the goal is to obtain as much information about the client’s figure as possible. Since most of my work involves Devere’s Handbook of Practical Cutting, 1866, I’m using his methods of measuring.

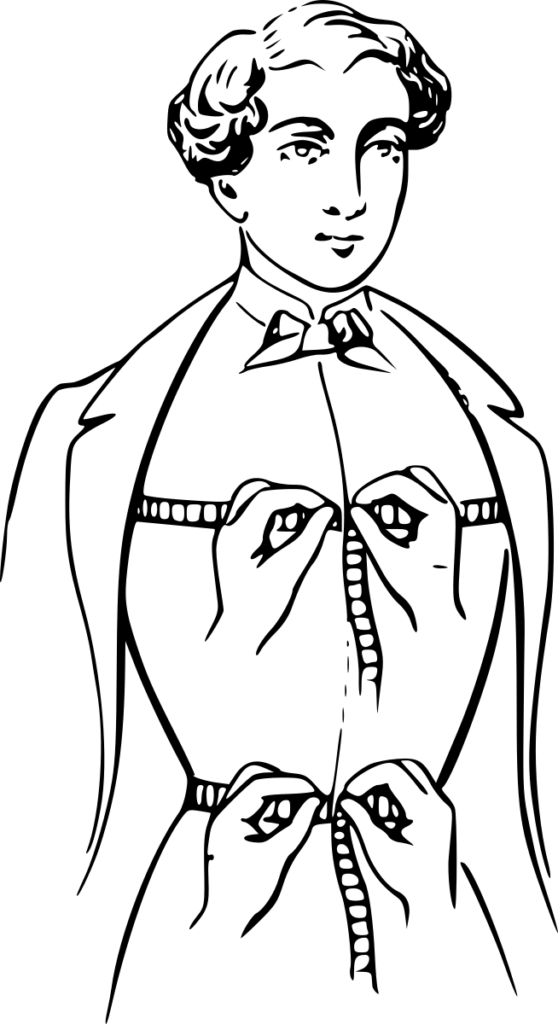

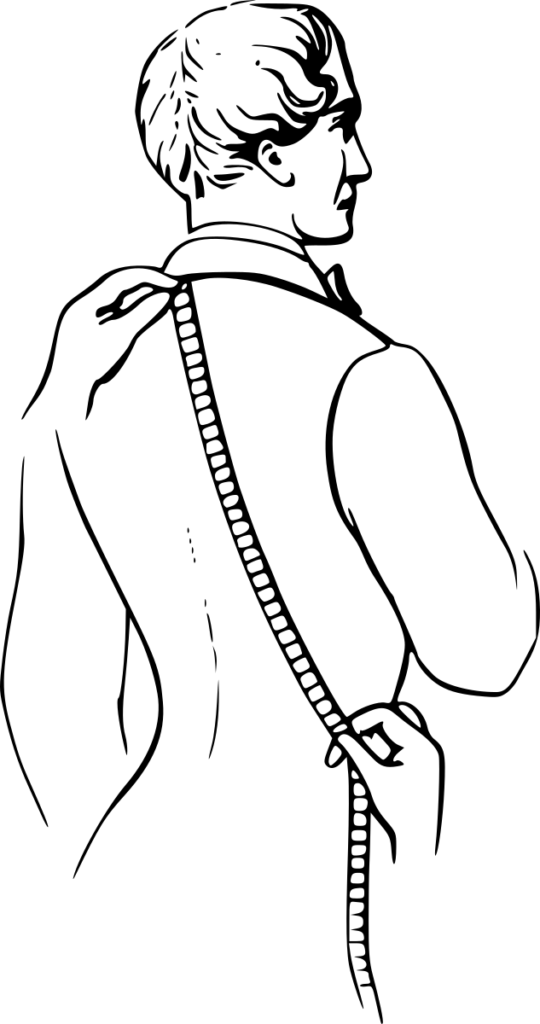

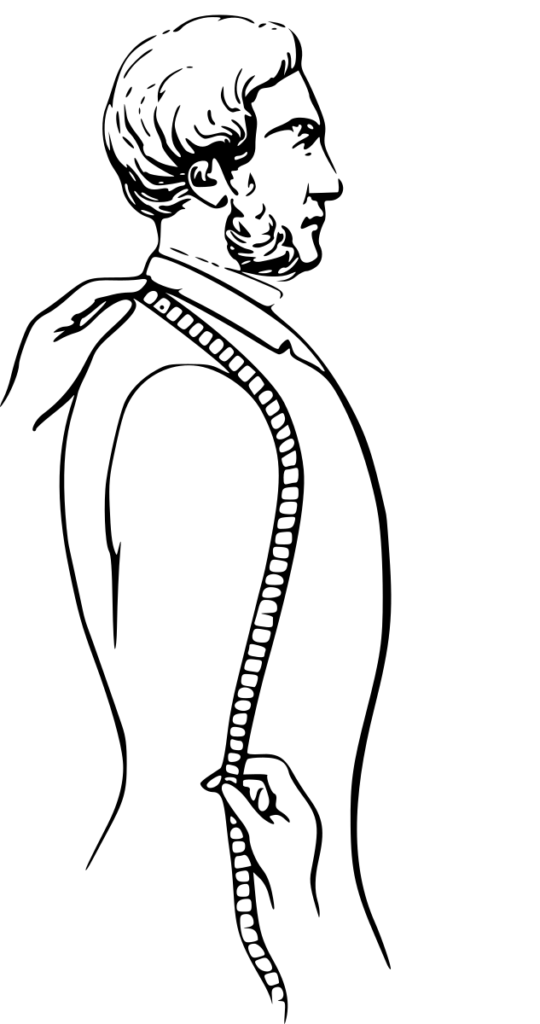

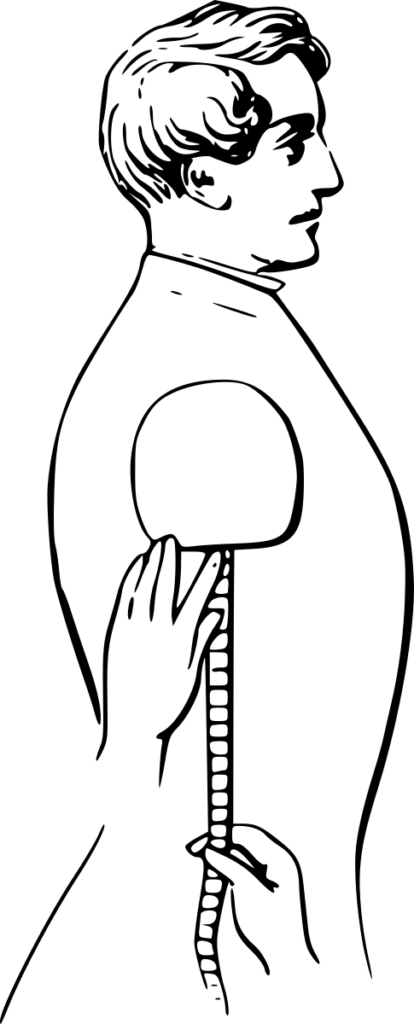

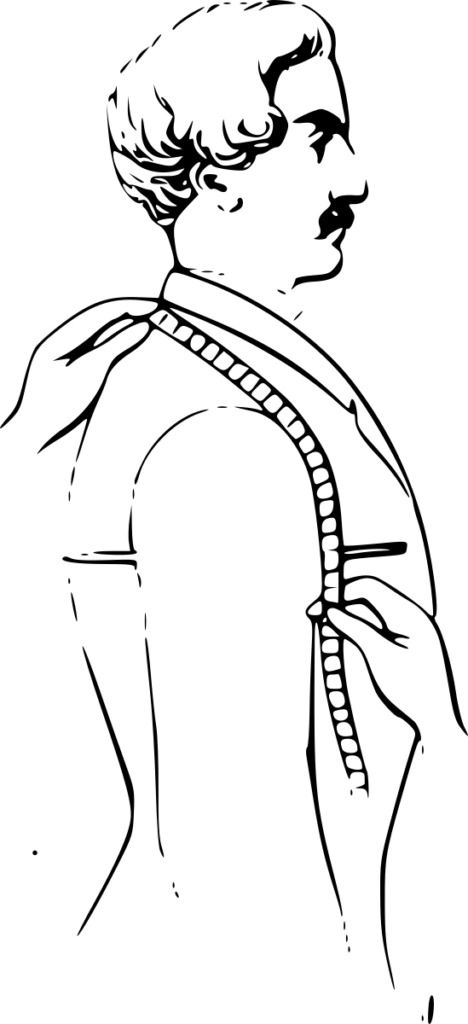

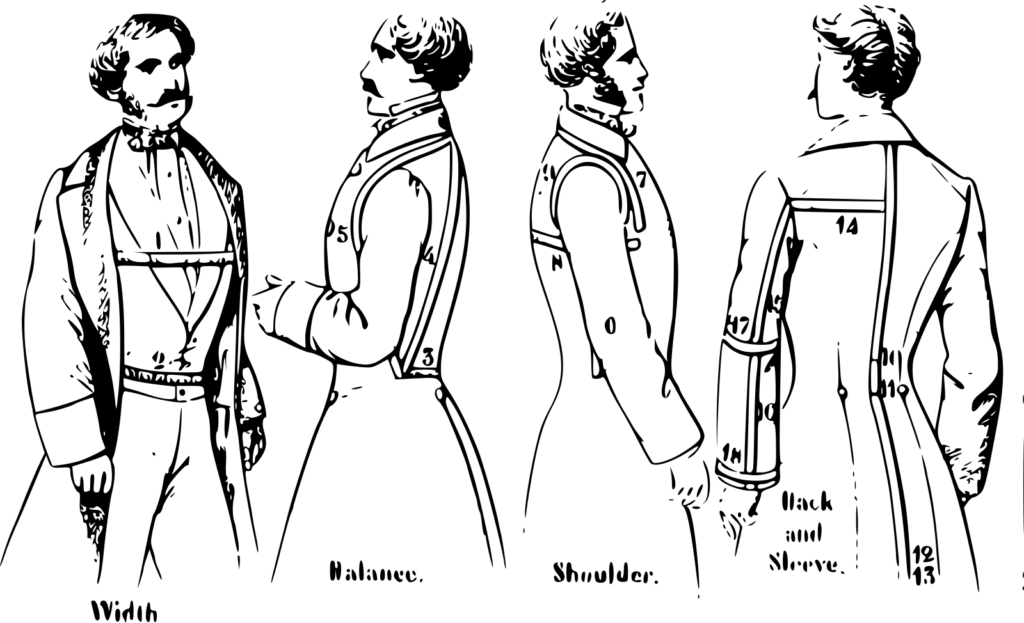

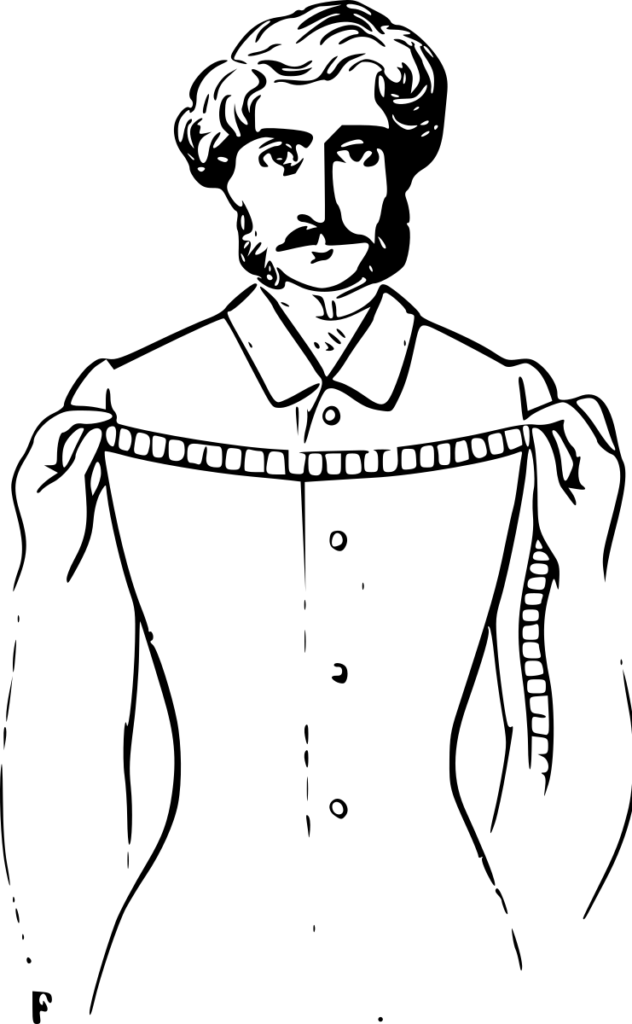

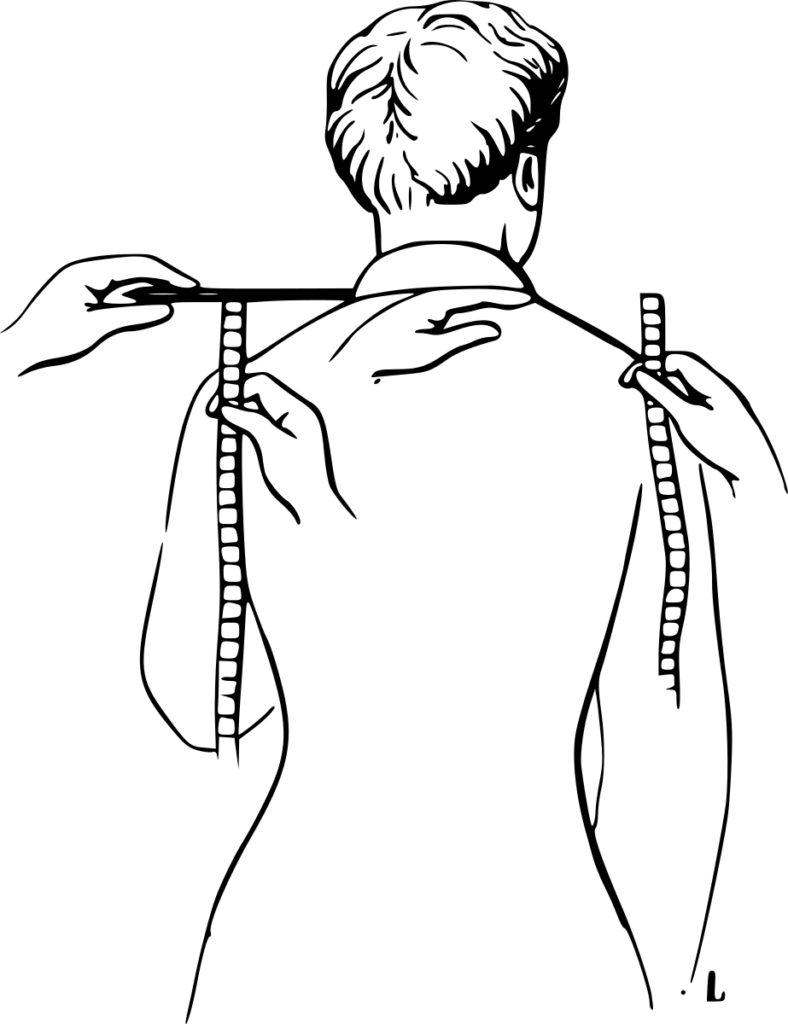

Devere’s book is very descriptive in the measurements taken, but in the 1866 version, is lacking in illustrations. It took me a good while to figure out exactly what each measurement involved, and where it was supposed to be taken. Then, a couple of months ago, I came across some illustrations from Journal des Tailleurs, a French tailoring magazine published by Devere in 1858. It contained some beautiful illustrations of how the measurements were to be taken, but of course, had no accompanying text. So what I’ve done is take the text from Devere’s 1866 manual, and combine it with the images from 1858, as well as some diagrams from his 1856 edition. Hopefully that will make it easier for those of you trying to learn how to draft from his book.

The First Series

Devere broke the measurements into three groups, or series, of six measurements each. The First Series comprises the sizes and lengths, and shows at once whether the man is Long or Short-Bodied, Stooping or Extra-Erect, Thin or Stout Waisted.

No. 1, Breast

This measure is taken on the Waistcoat, under the coat, as shown on figure blank. Place the tape horizontally, raising it up as high as possible under the arms, without raising it at the chest, and hold the tape with the thumb and forefinger of each hand. The tape must first be drawn very tight, and afterwards be loosened as the client breathes, so as to obtain the size of this part with the greatest accuracy. In writing it down we must only put the half; for instance, 18 ¾ inches for 37 ½ &c.

This measure indicates the graduated measure, to use in the draft. It is 18 ¾ in proportionate men.

No. 2, Waist

This measure is also taken under the coat: it goes round the body on a level with the hollow above the hips, see figure blank, and it should be taken rather easy. Like the breast measure, it is only written down as half the length taken; say 15 ¾ for 31 ½ inches.

This measure, by comparison with the breast, shows if the waist is thin or stout. In the proportionate man it is 15 ¾ or 3 less than the breast.

To mark the Centre Point

First button the coat, and press the body with the side of hand, just above the hips, to find the level of the hollow of waist, which is usually about 1 inch above the top of hip bone; make a short chalk mark horizontally at this level. Next place the brass end of the tape at the middle of back, on the same level as the chalk mark, and measure by the scale on the tape, the distance of the Centre Point from the middle of back, according to the size of waist; making a short chalk mark downwards at this distance, which with the first chalk mark will form a cross. The middle of this Cross is the Centre Point.

N.B. – If the client is wearing a loose-fitting coat, such as the paletot or a jacket, the fronts must be drawn together, or laid over, and fastened by pins or by a tape tied round the waist, so as to have the garment perfectly tight-fitting at the back, and over the hips. This being done, the Centre Point can be marked with as much accuracy as if the customer was wearing a dresscoat, and this is one great advantage of our especial System of Measurement.

Sadly, we don’t have access to Devere’s special rulers to find the Centre Point. So we have to use the formula of taking 2/5 of the Breast or 1/5 of the full chest and using that number to find the centre point. For example, a 35 inch chest measured all the way around would be 7 inches to the centre point. So find the center of the back at the waist level and measure 7 inches around to find the Centre Point.

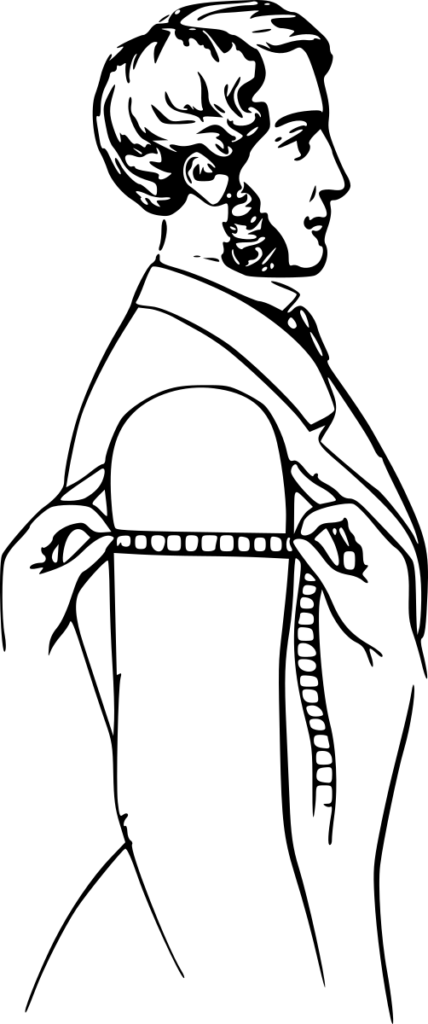

No. 3, Curve

Take the Bust and Curve part of the Tape, slip the eyelet-hole at the end of it over the head of the pin, and hold it there; the eyelet-hole must be exactly at the top of the back seam: then with the other hand carry the tape perfectly straight to the Centre Point, crossing the side seam near the middle, and not letting the tape be either very tight or too slack.

No. 4, Bust

Continue to hold the end of the tape at the top of back seam, and with the other hand pass the tape over the shoulder in front of the arm, close to the front of the scye, letting the clients arm hang down in its natural position; draw the tape very tight, to flatten any creases there may be at the front of arm, and carry it direct to the Centre Point.

Now as the Curve and Bust measures both start from the top of back (a point which is always fixed and certain), and proceed to the Centre Point which is also fixed and certain for all sizes and structures; the difference between these two measures must, it is evident, show the exact difference that there ought to be, between the lengths of back and forepart.

In a Proportionate man, the difference between these measures is 2 ½: it is less than this for stooping men, and more for Extra-erect men.

No. 5, Side

Pass a pencil or penholder through the loop at the end of tape, and hold it tight under the arm (the arm must not be raised up, but should lay close to the body). Then measure the length to the Centre Point, so as to ascertain exactly, the distance between this point and the bottom of scye.

This measure serves to rule the depth of the bottom of scye, and shows the degree in which it must be hollowed out below the side point. In proportionate men it is 8 ½, and is usuallyabout half the length of back to natural waist. It is longer for extra erect men, and for small or high shoulders; and less for stooping men, and for large or low shoulders.

No. 6, Depth of Scye

This measure, shown on figure blank, starts from the same place as Bust, but instead of proceeding to the centre point, it stops at the level of the bottom of scye. To ascertain this level exactly, place a pencil or a penholder horizontally under the arm of the client, and measure down to the top of pencil. This measure must be taken very tight. The only use of this measure is to control or prove the accuracy of the two last measure. The depth of scye and side are really only the bust measure, taken in two parts, and if added together should produce the same quantity: for example in the proporionate structure:

The depth of Scye is 12 ¾ And the side is 8 ½ Which is equal to the Bust 21 ¼

When these measures do not agree in this manner, there is evidently an error in one of them, and they must be measured over again.

Second Series

The Second Series, gives the measurement of all the parts which vary according to Fashion, or the taste of the client; such as the place of the hip buttons, the length of skirt, the size of sleeve, etc.

Unfortunately, I was unable to find such clear images for the secondary series. These will have to be drawn out by hand or edited from existing examples like the image above.

No. 7, Length of Back to Hip Buttons

Taken from the back neck, to the level of the top of back plaits. This measure is of course variable according to Fashion.

No. 8, Length to Bottom of Skirt

This is merely a continuation of the preceding measure, which is carried on from the notch to the bottom of skirt: its length is variable according to Fashion, taste, or the height of the client.

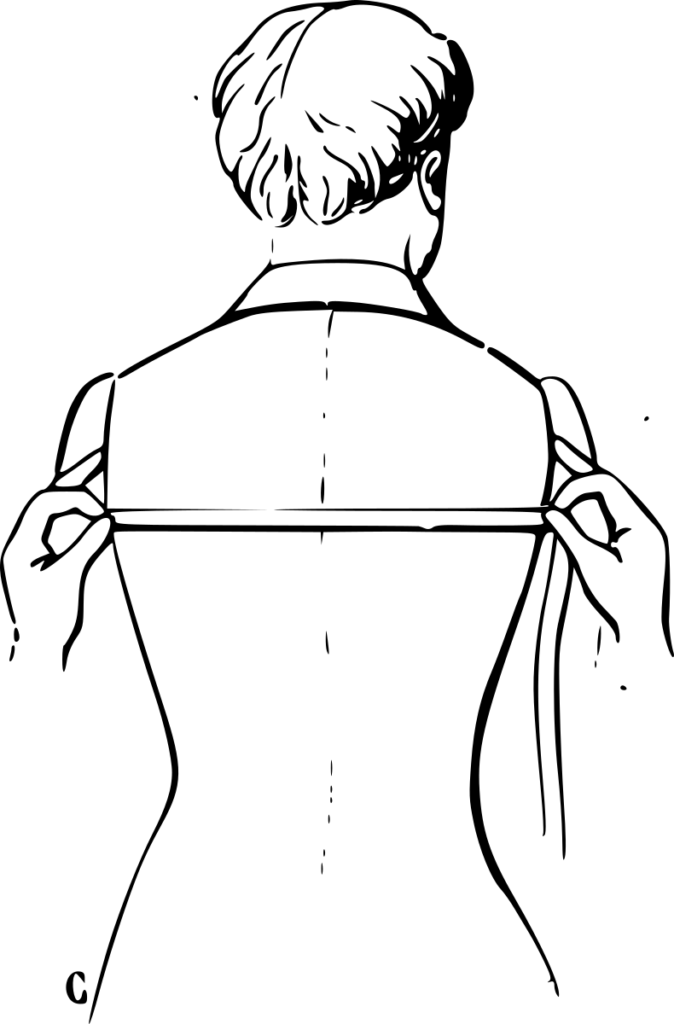

Nos. 9 and 10, Width of Back, and Length of Sleeve

These measures are taken in the usual way; first raising the arm square with the body and bending it at the elbow. Then take the tape and place the end in the middle of back, opposite the hind arm seam; measure first the width of back, according to fashion or the style of coat required; and then continue the measure along the seam of the sleeve to the wrist. By deducting the width of back from the whole length, we obtain the true length of sleeve with great exactness.

The width of back is usually about 7 ½ graduated inches, for all sizes and structures, and the length to wrist is 32 ½ inches in the proportionate man; which, deducting the back 7 ½, leaves 25 for the real length of the sleeve. The length of arm is subject to great variation: it will however as a general rule, be found in proportion to the height of the man.

No. 11, Elbow Width

Taken according to Fashion, or the wishes of the customer.

No. 12, Wrist

Measured tight, medium, or loose, as required. This measure, as well as the Elbow, should be written down as half, because it is only the half-measure that is used in drafting.

Supplementary Series

The supplementary Series is always to be taken, whenever there is much deviation from the proportionate structure. This Series of measures gives the exact form and position of the arm-hole: it shows whether the chest is round or flat, and the shoulder blades flat or prominent; whether the shoulder is high or low, large or small.

No. 13, Back Stretch

Taken across the back, at the level of the bottom of back scye. When we are taking this measure as part of the Supplementary Series, its accuracy becomes of great importance, and we have first to notice whether the coat the client is wearing, has the seam of the scye at its proper place. If it is a Paletot or Paletot Jacket, the back stretch will probably be too wide; if he has on a close-fitting coat of the old fashioned English cut, (in which the armhole is very large), it will be too narrow. The true width of back stretch, should be two-fifths of the breast measure, and this proportion should but rarely be deviated from. It may however, be 3/8 more than this, for very stooping men, and 3/8 less for extremely erect ones.

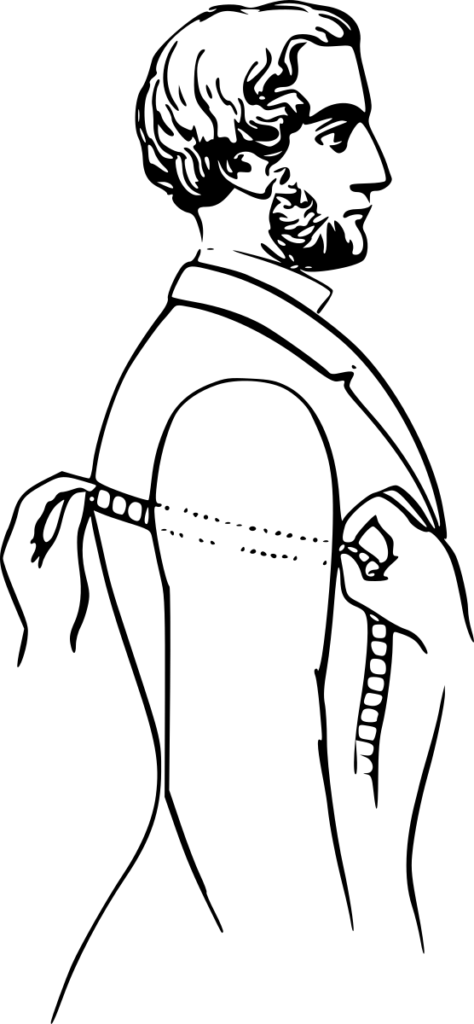

No. 14, Diameter of Arm

This measure gives the distance between the side point and the front of scye, and we obtain it by taking the tape between the thumb and forefing of each hand: then extend the other fingers square, those of one hand touching the front arm, those of the other hand touching the back of arm, and with the eye make the length of tape equal to the real diameter of arm.

This measure is 5 ¼ in the proportionate structure. It may be ½ inch more or less, according as the shoulders are large or small, forward or backward, but never exceeds this limit of variation.

No. 15, Front of Scye

To take this measure we pass a pencil through the loop and hold it against the front of arm with the thumb and forefinger of one hand; then pass the Tape under the arm, and carry it on with the right hand, as to touch the middle seam of the back at the level of the bottom of back stretch.

In the proportionate man, the front of scye is 12 ¾, or equal to the back stretch 7 ½. And diameter 5 ¼, added together.

It is important that the three last-named measures, Nos. 13, 14 and 15, should be taken with the greatest care and accuracy; and the student should practice taking them on the same man for some little time, and observe if the measures taken at different times are always alike. We generally find that there is at first, a tendency to take the diameter too small, and the front of scye too long.

By the examination and comparison of these three measures, we can see at once what is the degree of round required to be given to the side seam. In most cases, perhaps 70 out of very 100, the degree of roundness required is that indicated on plate 4, fig. 1. But there are men whose structures vary in this point: some have the back round and the shoulder blades very prominent, while others have the back very flat and the blade bones h ardly indicated.

Now in the proportionate man, we have seen that;

The back stretch 7 ½ Added to the diameter 5 ¼ Is equal to the front of Scye 12 ¾

But if the man had a very round back, we should not find this calculation correct, because, while neither the back stretch nor the diameter would at all vary, the l ength of the front of scye would increase, because this measure passes over the prominence of the shoulder blades: we should then find:

The Back Stretch 7 ½ The Diameter 5 ¼ And the Front of Scye 13 ¼, instead of 12 ¾

Showing that half inch more round than usual, is required on the side seam of forepart.

For a flat back, for an inverse reason, the front of scye will be found less, than the back stretch and diameter added together, and less round must be given to the side seam.

No. 16, Chest

To take this measure well, hold the tape with the thumb and forefinger of each hand, and place the ends of the fingers against the front of each arm. We thus obtain the whole width of chest, which must be halved before writing it down. This measure is 8 ½ in the proportionate structure, or 1 more than the width of back stretch. It will be shorter or longer, according as the shoulder is forward or backward, or the chest flat or prominent.

No. 17, Slope

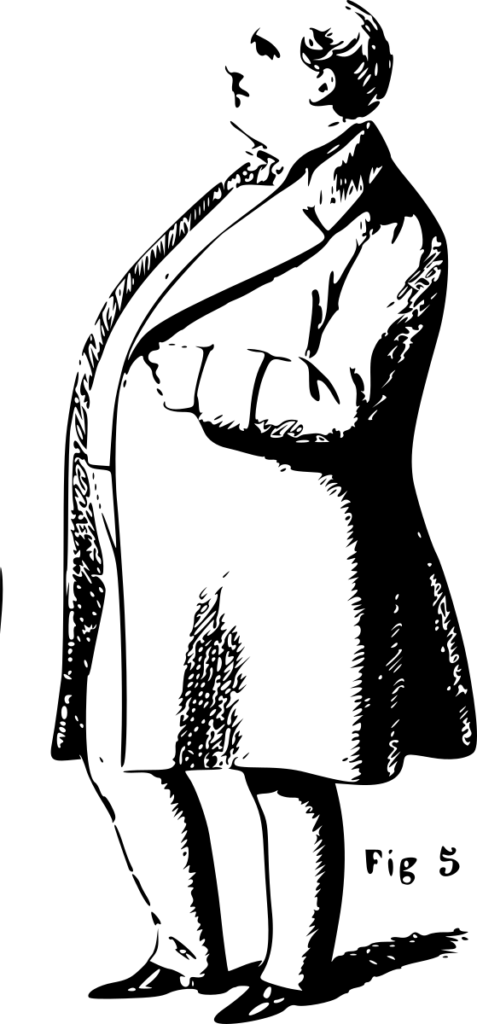

The use of this measure, is to show the degree of slope required to be given to the top of shoulder. The manner of taking it is shown by fig. 5 S. Pass the pencil through the loop at the end of tape; place one end against the side of neck, and hold the pencil horizontally with one hand; then with the other hand measure the distance between the pencil and the top of shoulder.

The slope is 2 in the proportionate structure, but it may vary to 2 ¾ for very low or sloping shoulders, or decrease to 1 ½, 1, or even ½ an inch, for very high shoulders. We hardly ever find shoulders more sloping than 2 ¾, and even this degree is not often met with. High shoulders are more frequently found, though they never have less slope than ½ an inch, except in cases of deformity. Some men have one shoulder higher than the other, and for these the measures of both shoulders must be taken.

No. 18, Round of Scye

Measured round the armhole in the usual way, and serving to show whether the shoulders are large or small: it is therefore useful in some cases, as a guide for the slope of shoulder. It also may be used in the draft of sleeve. It is usually about 2 ¼ less than the breast measure in the proportionate structure: if there is a greater difference than this, the shoulder is small, if a less it is large.

In applying this measure to the pattern to prove the size of the armhole, care must be taken to deduct about ¾ of an inch for the stretching in front of the scye.

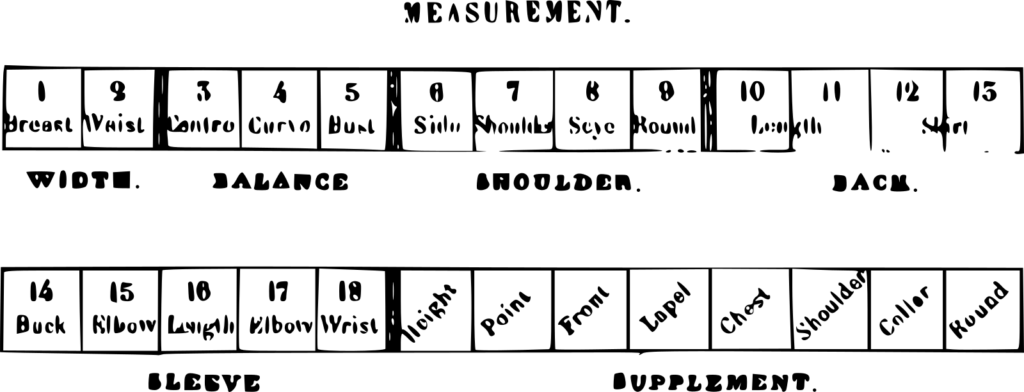

How to Write Down the Measures (Traditional Method)

We have now described the complete series of measures which we consider necessary, and we have, at the bottom of plate 4 shown on fig. 7 the manner in which, when taking these measures, we write them down in three distinct lines, each containing one series.

In the first line we put first the Breast and Waist; then Curve, Bust, Side, and Depth of Scye.

In the Second line. Length to the hip buttons, ditto to the bottom of skirt, then Width of back, Length of wrist, Width of Elbow and Wrist.

In the Third line (when this series is taken), we put Back stretch, Diameter, Front of Scye, Chest, Slope and Round of Scye.

The first series must always be taken in every case. The second series may be taken or not, as preferred. The Third series should always be taken, whenever it is seen that there is any great deviation from the proportionate structure.

Be aware that that diagram above is from the 1856 edition, while I’m using the 1866 edition for my measurements. That’s why the numbers are not aligned with my measurement numbers.

A More Modern Method

Provided with the files you downloaded is an OpenOffice or Mircosoft Excel Spreadsheet file. Your task now is to take the measurements, and record them into that spreadsheet.

As you fill in the numbers, you’ll find the bottom half of the spreadsheet fills in with numbers. This will be extremely useful inthe next section of the class, drafting your custom pattern.

If you have any errors, or have trouble figuring out a measurement, please let me know!

Bagging the Waistcoat

We will now begin the process of bagging the waistcoat, which is a process used to assemble the waistcoat pieces into one unit.

Begin by sewing the two halves of the back lining together, if you have not done so already. Press open.

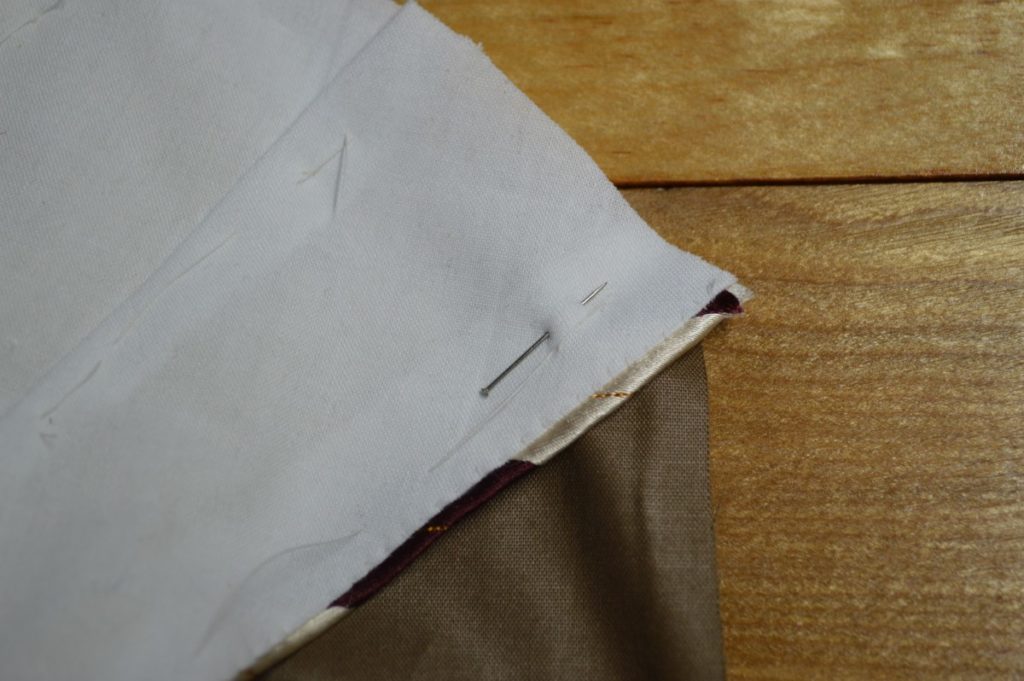

Lay the lining and back pieces right side together and baste along the bottom waist edge. Fold the seam allowance to one side on both top and bottom. The end of the center back seam should line up precisely between back and lining.

Using a quarter inch seam allowance, sew from the side seam, along the bottom waist, stopping at that point in the center back. Remember that it is very important that the seam allowances are folded out of the way and not caught in the stitching.

Repeat from the other side. Here is the result from the back side.

Remove the basting stitches along the waist and open up the back assembly, press open the curved areas (not shown for some reason), placing the back facing away from you, right sides up, as shown.

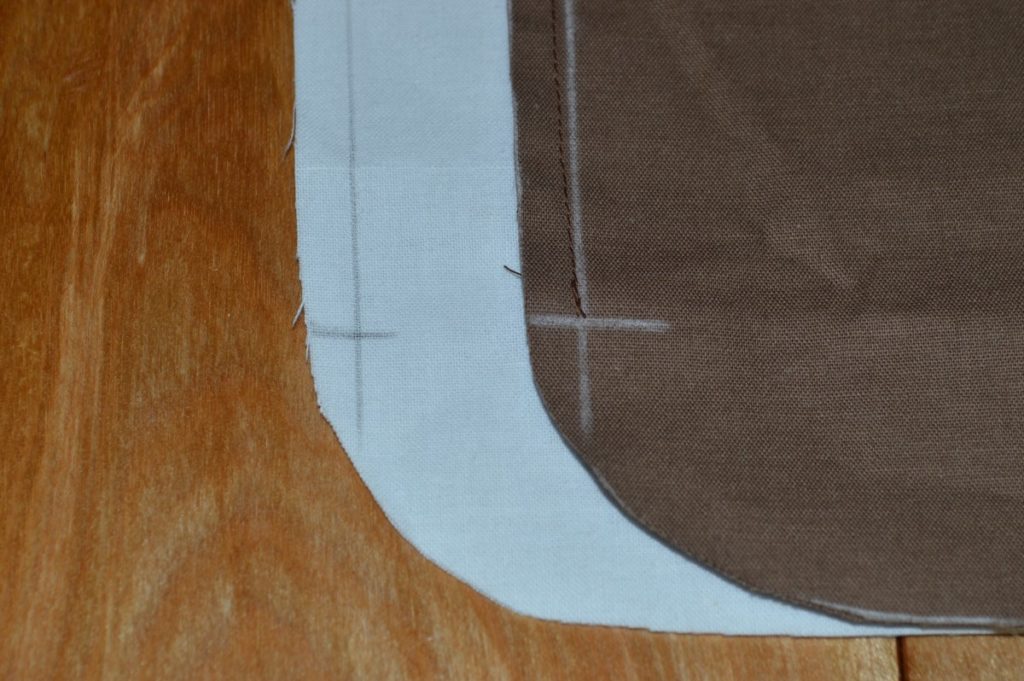

Lay the appropriate half of the forepart on to the back piece, right sides together.

I thought I had taken a clear photo of this, but there should be 1/4″ to 3/8″ of the back appearing beyond the top of the side seam. And at the bottom of the side seam, you can just see a small triangle of the brown fabric peaking through. Try to leave at least 1/8″ there so that the back lining can roll around to the inside of the finished vest at the waist seam.

Baste the forepart to the back along the side seam.

At the top of the shoulder seam on the back, mark a quarter inch, indicating the seam allowance of the neck and shoulder seam.

This corresponds to the point where the forepart meets the collar.

Pin the corner of the forepart at the top of the armscye to the corresponding point on the back. I rarely use pins, but this is one place where they are useful. Note how the forepart seems to extend beyond the edge of the back — this is so that the seam lines will match up properly.

Now match the other end of the shoulder seam on the forepart with the mark you made on the back. This is kind of confusing, especially if this is your first time trying this method, but just think things through and it should work out. Pin in place.

Here’s the same point from the right sides, with the mark lining up with the edge of the forepart and collar seam.

Now baste across the top of the shoulder seam, distributing the fullness as you go. Remove the two pins.

Repeat the process for the other forepart.

It is likely that the forepart extends below the waist seam. If this is the case, simply fold the bottom points upward and out of the way so that you are free to work on the next steps.

Fold the lining up over the forepart, sandwiching the forepart between the lining and the back. Baste along the side seam.

I don’t usually do this, but for clarity, you can mark the top of the side seam, precisely at the edge of the forepart underneath.

Now baste the armscye of the lining and back together, making sure not to catch the forepart underneath.

At the top of the armscye, you can again mark the edge of the forepart, indicating where the stitch line should turn. The edge of the forepart should ideally meet the 1/4″ seam allowance of both back and lining at the same point.

Baste along the top of the shoulder seam.

The neck edge of the lining should extend 1/2″ beyond the collar and neck seam.

Then mark a quarter inch away from the collar and neck seam of the forepart, indicating the end of the stitching.

Repeat for the other side. Believe it or not, this will actually turn into a waistcoat!

Now stitch from the bottom of the side seam, to the top of the side seam where you made the mark . . .

Along the armscye to the next mark . . .

And across the shoulder seam to the final mark. You need to be careful here, because it is very easy for the lining fabric to stretch slightly, hence why I did not go all the way to the mark.

Repeat for the other side of the waistcoat.

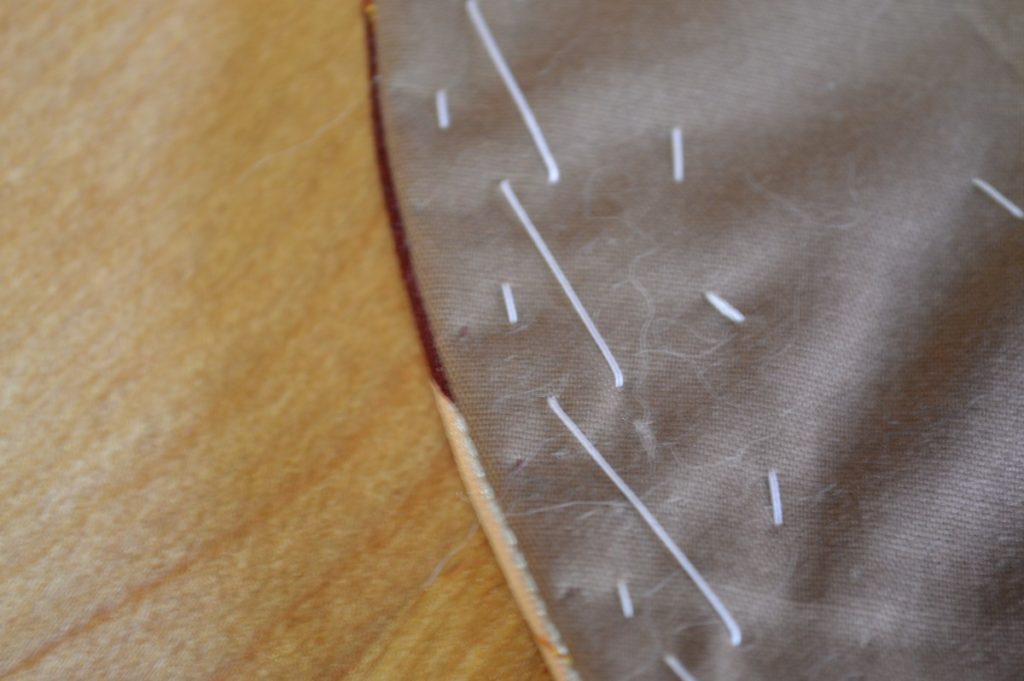

Before moving on, you must remove all of the basting stitches you just put in. Some of them are hidden from the lining side, so I like to work from the back side. Make sure to get them all, I always seem to miss a few.

This is sadly not pictured, I couldn’t figure out the best way to photograph it, but after removing the basting stitches, carefully pull the forepart out through the neck opening. Make sure not to stretch the fabric in the neck area — be gentle!

Then smooth out the bottom of the back pieces, and press the back waist, side seam, armscye, and shoulder seams.

If everything has gone according to plan, you should have a similar result. All that is left is to close up the neck.

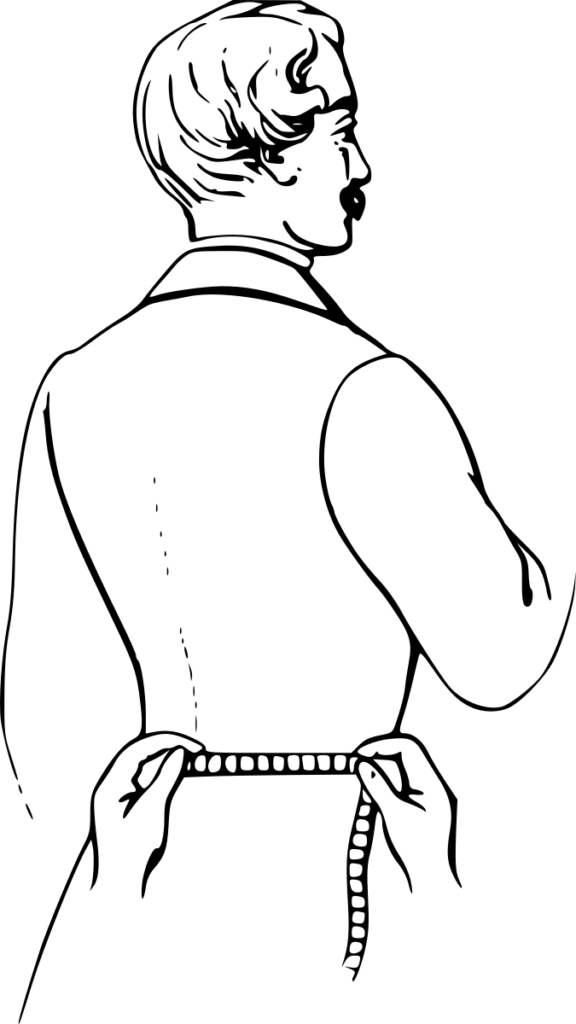

The Back Belt

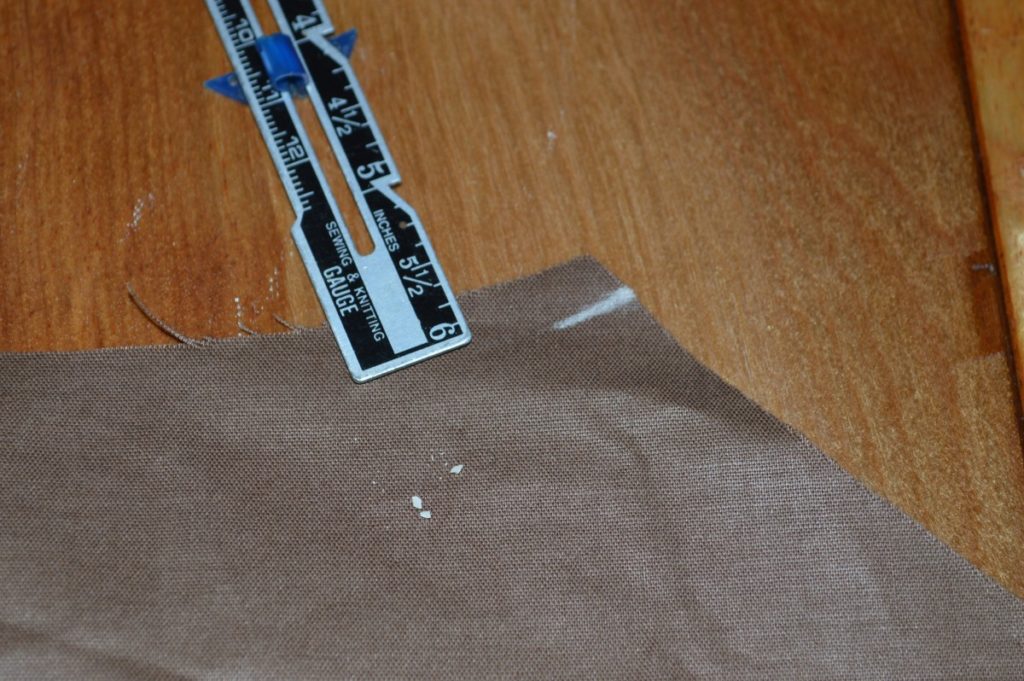

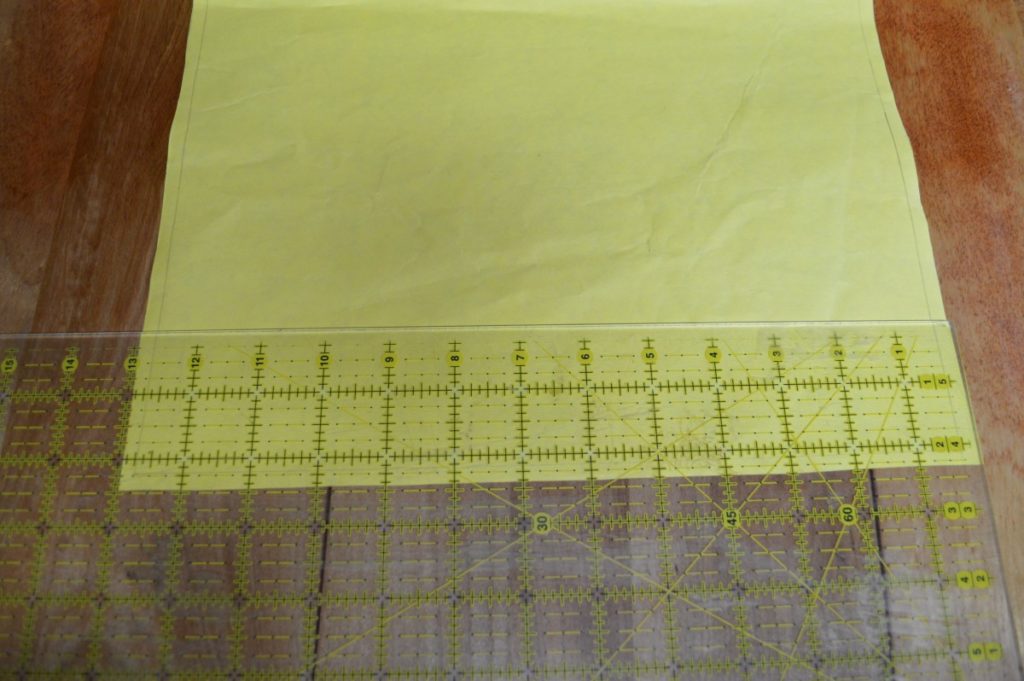

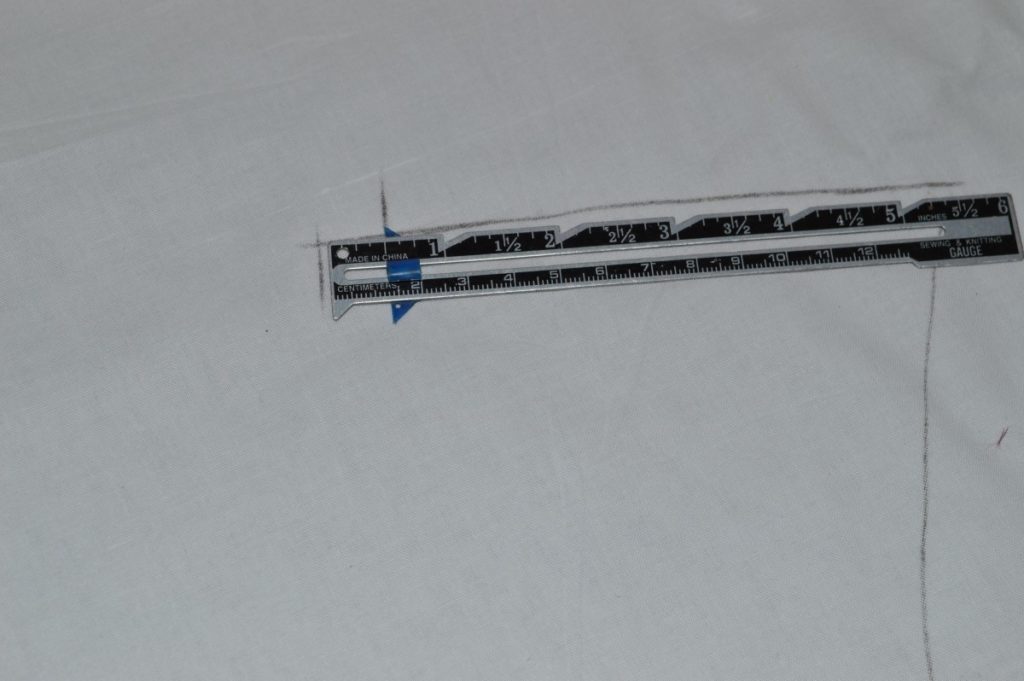

Onto the back belt! This is a fun little bit that I’ve always enjoyed doing, as it means the vest is nearing completion. Begin by measuring the width of the vest back, at about 3 inches above the waist. My pattern is pretty much parallel, hence putting the ruler at only 2 1/2″.

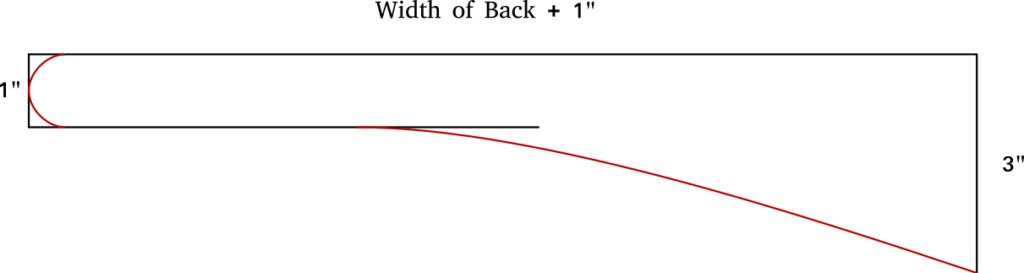

To draw the pattern, make a horizontal line equal to the length of the back plus 1″. The extra inch gives us a bit of extra room for adjustment, if necessary.

On one end, make a perpendicular line 3″ in length, and on the other, a line 1″ in length. The narrow end should be equal to the width of your vest buckle.

Draw a parallel line along the bottom edge, 1″ from the top. Complete the curves as shown in red.

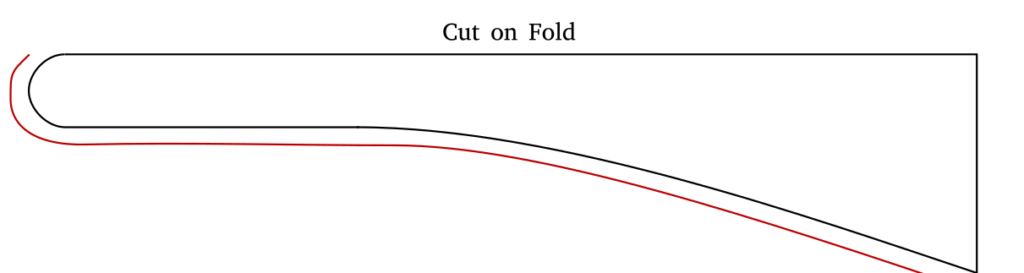

Complete the pattern by adding a 1/4″ seam allowance along the rounded end and bottom of the buckle. The top edge is cut on the fold.

Place your pattern on the fabric, matching the top edge of the pattern to the fold in the fabric, and trace.

Cut out two belts, as shown.

Baste the belts along the center, right sides together, and sew along the rounded corner and bottom edge using a 1/4″ seam allowance.

Trim the rounded edge to about 1/8″, as shown. Down get any closer, as it will have a tendency to fray.

Remove the basting stitches, and turn right side out. I usually use a pair of blunt scissors to aid in this step. Press so that the underside of the seam is not visible from the visible side.

The pattern for the back as drafted gives us a straight edge across the bottom. If you wish to have the center back curve upward slightly, the following instructions can be followed.

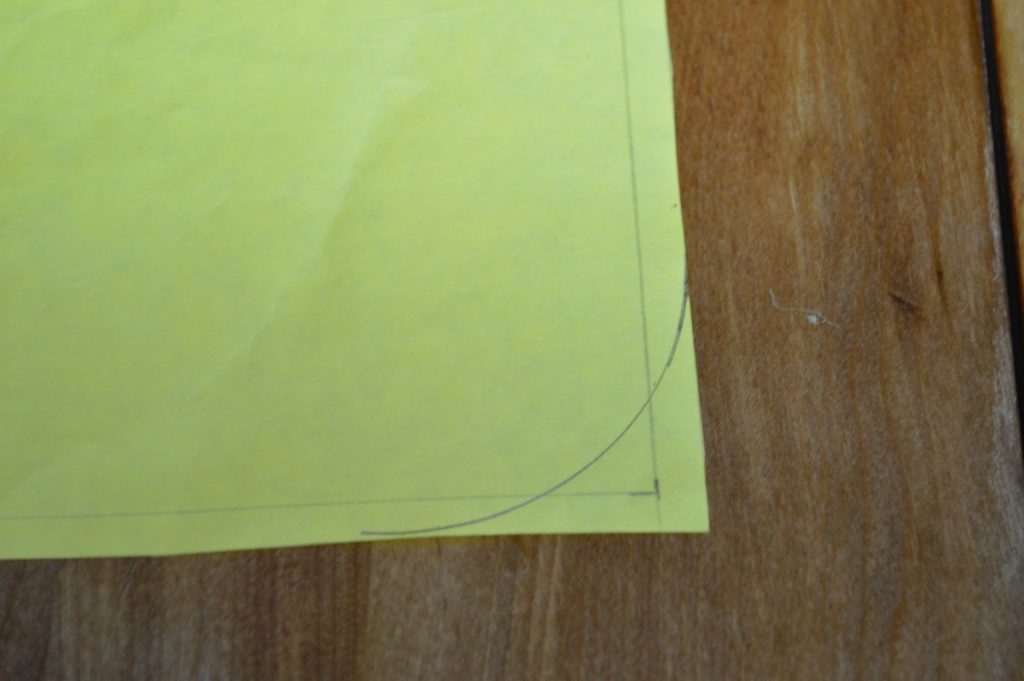

Draw a curve along the center and waist seam intersection of the back. This can be done freehanded, or you can use a tin can or some other round object, like I did.

Trim the altered pattern.

This next step is extremely important in terms of accuracy, and affect how the center back will lay when completed. First, draw a line parallel to the center back, 1/4″ from the edge, indicating the seam allowance. Draw another shorter line intersecting the first line, at the precise location where the curve begins. Do this to both pieces of both the lining and back.

Sew the center back seam together, from the neck to the intersection of the two lines. You can baste the pieces first but I find the natural tension of the fabrics is enough to hold things together.

You can see how the marks where transferred to the lining as well.

Press the center back seam open, and then lay the belts into position on the backs. The position of the top edge will vary, but it should be at the position of your natural waist. In my case, it was about 5″ from the bottom. Make sure the top edge is square all the way across.

Baste the buckle in place across the width of the back.

About four or five inches from the side seam, mark a vertical line across the height of the belt, indicating the stitch line.

Top stitch, either by hand or machine, along the top edge, down the chalk line, and along the bottom edge, staying about 1/16″ away from the edge of the belt.

This completes construction of the belt. All basting stitches remain in place until the vest is finished.

Installing the Lining

Now we are ready to install the lining. Lay the lining into place onto the inside of the forepart, wrong sides together, ensuring there is enough overlap on the edges to turn under and cover the facing edges.

Baste from the top of the shoulder, slightly off center, down to the waist.

Turn under the raw edges 1/4″ (feel free to adjust that if necessary), and baste in place along the waist and front edge of the lining.

To the side of the basting stitches in the shoulder, form a small pleat, about 1 inch in total width (1/2″ on each side), and about 5 inches long. This gives some extra room for movement in the lining, both for comfort and to avoid the lining pulling on the forepart.

Baste the pleat and press lightly.

Along the armscye, again turn under the lining fabric and baste it in place, the folded edge being about 1/8 from the edge. You may have to stretch the lining with your fingers around the tight curve of the armscye.

Fell down the folded edge of the lining along the armscye, waist, and front edge.

On the side seam and shoulder seam, trim off any excess fabric and facing, and cleaning up the edges if they are fraying.

The Armscye

Just after attaching the facings, I like to finish off the armscye before adding the lining in.

First, mark around the canvas on the armscye at a distance of 3/8″.

Now, carefully trim away the canvas around the outside, making sure not to catch the fabric underneath.

Now, fold up the fashion fabric over to the wrong side of the canvas and baste. Then press flat.

Now using a cross stitch, working left to right (or the other way if you’re left handed), stitch the folded edge of the armscye to the canvas below. Try not to let your stitches show through on the right side.

Repeat for the opposite armscye.

The Facings

To begin construction of the facing, first lay out your parts as shown. It’s easy to get the waist facing facing the wrong way, leading to a misalignment when attaching it to the forepart.

With right sides together, baste the facing pieces together along the inner edge of each.

Sew with a 1/4″ seam allowance. While we originally added a 1/2″ seam allowance, that extra 1/4″ is taken up by the front facing.

Press over the waist facing. The seam is not opened up, rather, the front facing lays completely flat.

Lay the facing into position on the forepart. Remember that you added an extra 1/2″ around the front and bottom edges, so they should extend off the edge of the forepart. Baste everything in place along the waist, center front, and collar.

As you get to the roll line area of the collar, hold the facing slightly loose as you baste, to give some ease when everything is turned right side out. This will help the collar lay flat. I give about 1/4″ of ease, spread out about 1/2″ on either side of the roll line. You can just make it out in the photo, with the two ripples that are showing in the facing.

Continue basting up to the top of the collar.

After the basting is complete and you are happy with everything, turn the forepart over and trim off the extra bit of facing along the collar, center front, and waist.

Sew along the collar, center front, and waist with a 1/4″ seam allowance.

By sewing with the facing on the underside, you will help ensure the fullness near the roll line is distributed evenly. By machine, the feed dog will aid you. By hand, use your fingers to fine tune the distribution for each stitch.

When you get to the center front and waist corner, take two stitches on a diagonal, instead of making a sharp turn. This will give the seam allowance more room when you turn everything right side out.

Trim the seam allowance at the corner to about 1/8″. It’s not a good idea to trim further, as the material has a tendency to fray through to the other side of the stitching, shortening the life of the waistcoat.

After removing the basting stitches you just put in, carefully turn the facing right side out, smoothing with your fingers. You want the facing to stop about 1/16″ to 1/8″ from the underside, so that it will not be visible on the right side. Baste about 1/2″ from the edge as you work along. At the bottom corner, you might have to use something to help you get a crisp corner, such as an unsharpened pencil or pen, closed scissors, etc.

Keep up with the basting. When you get to the roll line, you’ll want the facing to now extend 1/16″ to 1/8″ beyond the forepart, as when it is folded over, it will hide the seam underneath.

Here’s a closeup of how the facing is extending beyond the forepart, above the roll line. Below the roll line, down the center front and across the waist, it is the opposite.

Continue basting up to the top of the collar, keeping the facing extended beyond the collar.

Now, we need to ensure that the collar rolls (or in the case of a waistcoat, folds) properly over the forepart. Since the facing is on the outside, the distance around the roll line is longer than that of the forepart.

Holding the collar in its finished position, begin basting at the fullest section of the collar, about 1/2″ from the edge, towards the roll line, and finishing 1/2″ beyond the roll line.

You’ll have to open up the collar as shown to get the last stitch in beyond the roll line.

With the collar still in its final position, baste along the roll line on the collar side, 1/2″ from the roll line.

Finish the basting about 1″ from the end of the collar. I basted too far and had to unpick a few stitches when I went to finish the collar in the next module.

Open the collar and with the front of the forepart facing down, baste 1/2″ from the roll line on the facing side in a similar manner as above. The previous row of basting stitches holds the facing in place along the collar, at the right tension.

Now baste the inner edge of the waist facing down as shown. Distribute any fullness near the front corner with your fingers.

Continue basting along the inside edge of the front facing, through all layers, about 1/2″ from the edge.

Continue basting to the shoulder seam, stopping about 1″ from the end.

Here is the result so far. The collar should almost feel like it wants to pull itself into position atop the forepart, thanks to all of the work we did basting and distributing the tension properly.

With either a machine stitch, which was very common, or a side stitch by hand, top stitch along the waist, center front, and collar, 1/8″ from the edge. This firms up the edge and makes it much more durable, as well as helps to prevent it from rolling one way or the other.

When you get to the collar, the right side will be underneath, so it’s important to keep an accurate distance from the edge for a good appearance.

End your top stitching 1″ from the end of the collar, unless you wish to join me in picking out stitches later on.

With the basting and top stitching complete, we’ll now permanently baste the inner edge of the facing in place, with smaller stitches and matching silk thread. The stitches go through the facing and canvas only (and the padding, when you get to it). Be sure not to let the stitches show through to the right side.

Baste along the entire inner edge. The stitches should be within 1/4″ from the edge.

This completes the installation of the facings.

Cutting the Facing and Lining

It is now time to cut out the facings and lining pieces for the waistcoat. While one could use a paper pattern derived from their original draft, I find it is often easier, especially for one-off projects, to simply take the pattern from the forepart itself. In addition, facings were usually constructed without and darts or seam lines between the collar and forepart sections, so as to give a more continuous look to the finished vest, which makes using a paper pattern slightly problematic.

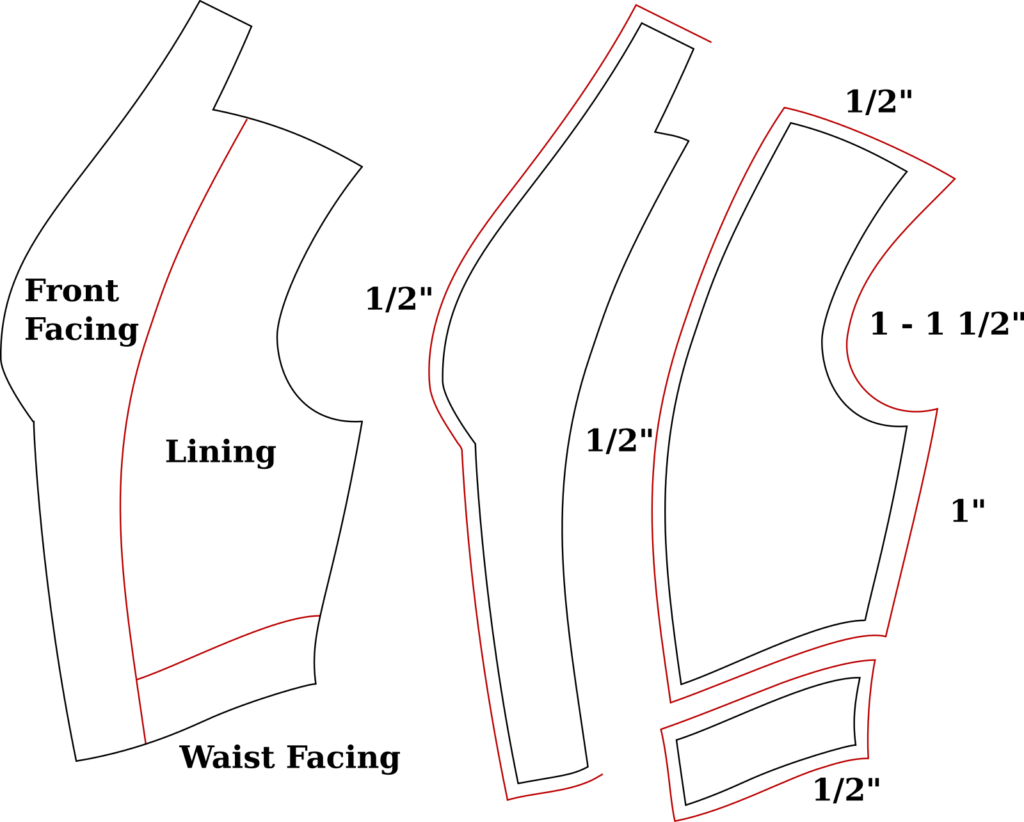

Here are two diagrams showing the result we are looking for. The first shows the exact seam line of the facing and lining. The second shows the seam allowances added. We need to add extra allowance to allow the facing to drape properly over the darted forepart and give us some extra ease to work with.

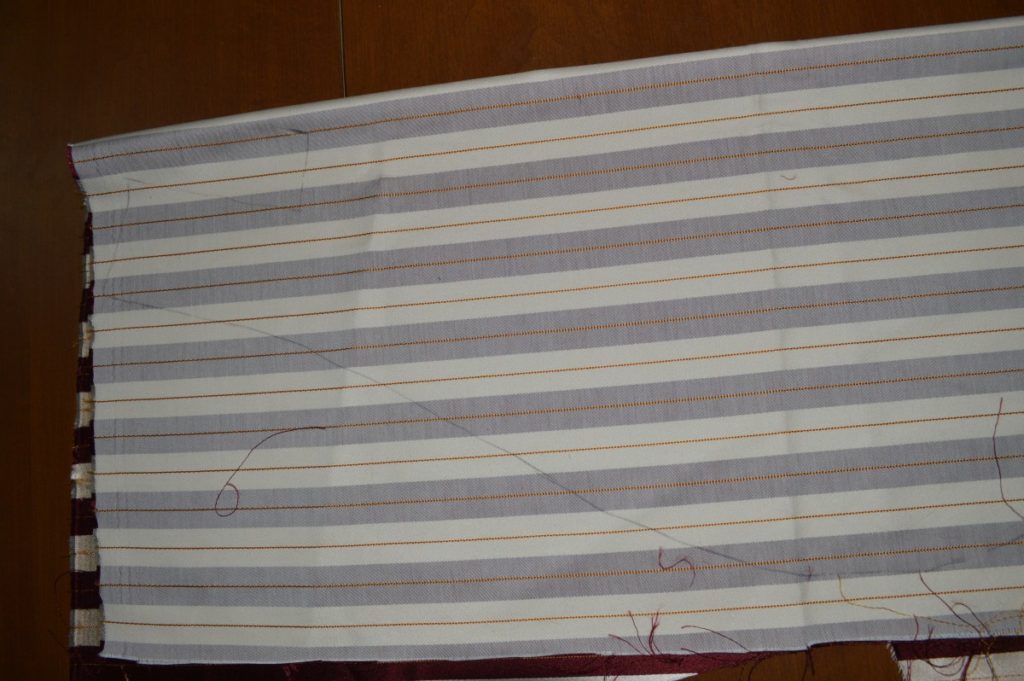

To begin, align your fabric fabric on the table, right sides together, and place the forepart on top, as shown. Along the center front, try to have the seam line, which is 1/4″ from the center, fall in the middle of a stripe, for a better visual appearance.

Along the shoulder line, at a distance about 1 1/2″ from the collar, make a chalk mark. This denotes the width of the facing. Note that this measurement can vary depending upon preference, originals you are copying, etc.

Along the bottom waist, about 3″ from the front edge, make another mark for the bottom of the facing. Again this can vary.

Now trace around the forepart, from the shoulder mark, around the collar, and down the center front to the lower mark. I removed the forepart here for more clarity in the photo.

Now connect the two dots with a graceful curve, completing the inner edge of the facing. Refer to the diagrams above for more clarity.

The lower end of the facing should be pretty much parallel with the front edge of the forepart.

Along the top edge and front of the collar section, and the bottom of the facing, add a 1/2″ allowance (or more if you feel nervous about it), to give us some ease when putting everything together later.

When you are satisfied with the shape and allowances, cut out the front facing.

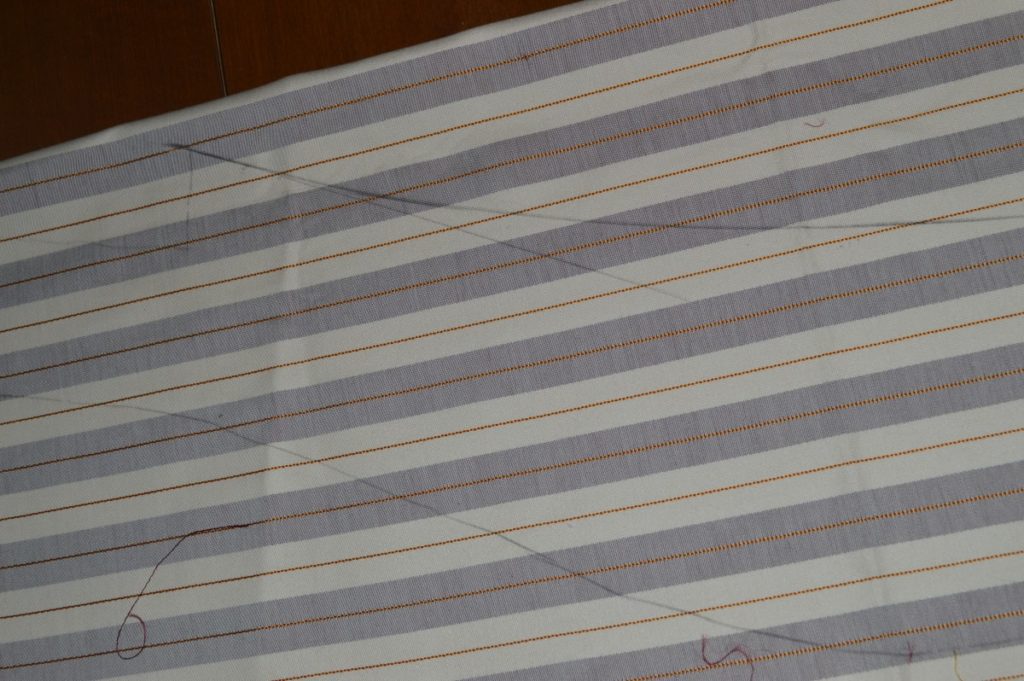

The waist facing piece is now cut out in a similar manner. Lay your fabric out as before, and place the bottom of the forepart on top. While you could align the stripes between the facings, it is not necessary. I chose not to match the stripes so as to save fabric.

Transfer the mark you made for the bottom of the facing onto the cloth.

About two or three inches from the bottom of the side seam, make another mark, denoting the top of the waist facing. Trace around the bottom of the forepart, from this mark, along the waist, and partway up the center front.

Now lay the front facing in position on top of the outline you just drew. Remember you added an allowance to the center front, so make sure to offset it the same distance.

Trace along the inner edge of the front facing, as shown.

Add a seam allowance equal to twice the seam allowance you are planning on using, which would be a total of 1/2″ in this case. This allowance extends towards the front of the forepart. Also add a 1/2″ allowance along the bottom and side seam (not shown).

Now draw a line for the top of the waist facing, following the general curves of the waist. I have two lines here only because I was not happy with my first try.

Cut out the waist facing. Note that I added an extra 1/2″ allowance along the bottom and side seam.

Cutting the Lining

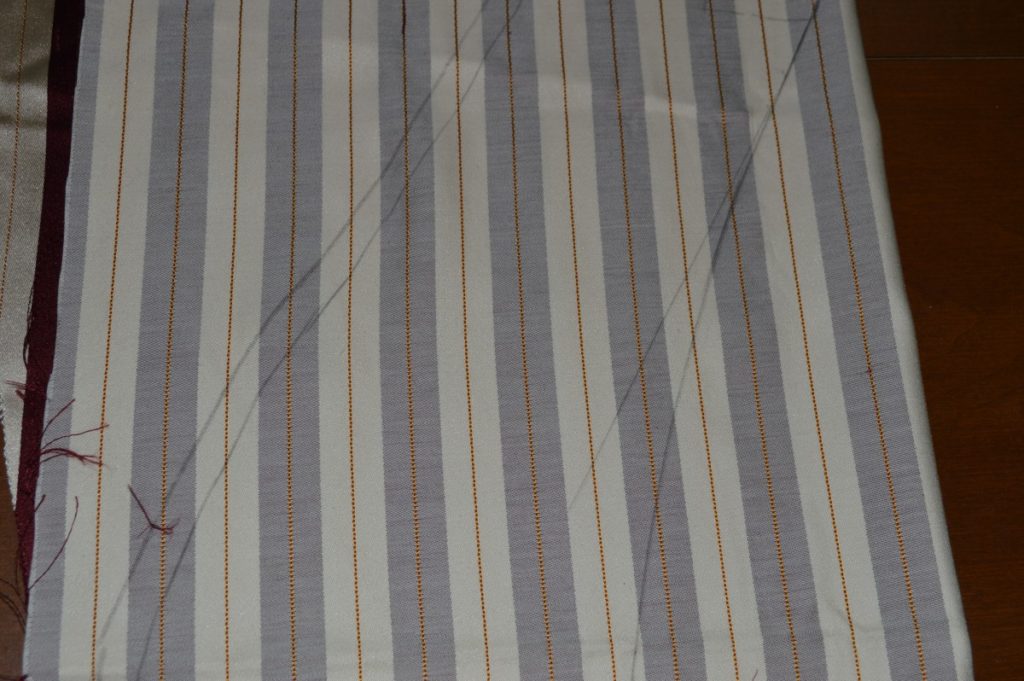

Lay the forepart on top of your doubled lining fabric – in this case I am using a cotton muslin.

Transfer the mark you made on the forepart shoulder to the lining fabric and begin tracing around the shoulder, armscye, and side seam.

Transfer the mark on the side seam indicating the top of the waist facing to the lining fabric.

Continue along the bottom of the waist, ending at the mark you made on the forepart for the front facing. Transfer that mark.

Here is the result so far. Note how the three marks are clearly indicated.

At the shoulder mark, add an additional 1/2″ to give yourself a seam allowance. This 1/2″ is twice our normal seam allowance of 1/4″.

Add a similar amount along the bottom waist.

Now lay the cut out front facing on top of the lining fabric, lining up the inner edge of the facing with the two marks you just made. Trace along this edge, giving you the front edge of the lining.

Now we must determine the position of the bottom seam of the lining. Along the side seam, lower the mark 1/2″, giving us a seam allowance. Lay the waist facing in position, and trace along the top of the facing, giving us the lower edge of the lining.

Here is my progress so far.

Before cutting, add at least 1″ allowance to the side and armscye, enlarging that allowance to 1 1/2″ at the top of the armscye. I also added 1/2″ along the shoulder seam. These give us some room for error, and can be trimmed after the lining has been installed. Cut out the lining.