Author: James Williams

Securing the Lining

There are just a few odds and ends left on the coat to finish. First

baste the remaining unfinished lining down to the collar piping,

using a basting diagonal stitch. Use black silk for this so that it will

be invisible if the collar ends up not completely covering it. The

stitches should be about 1⁄4 inch in length.

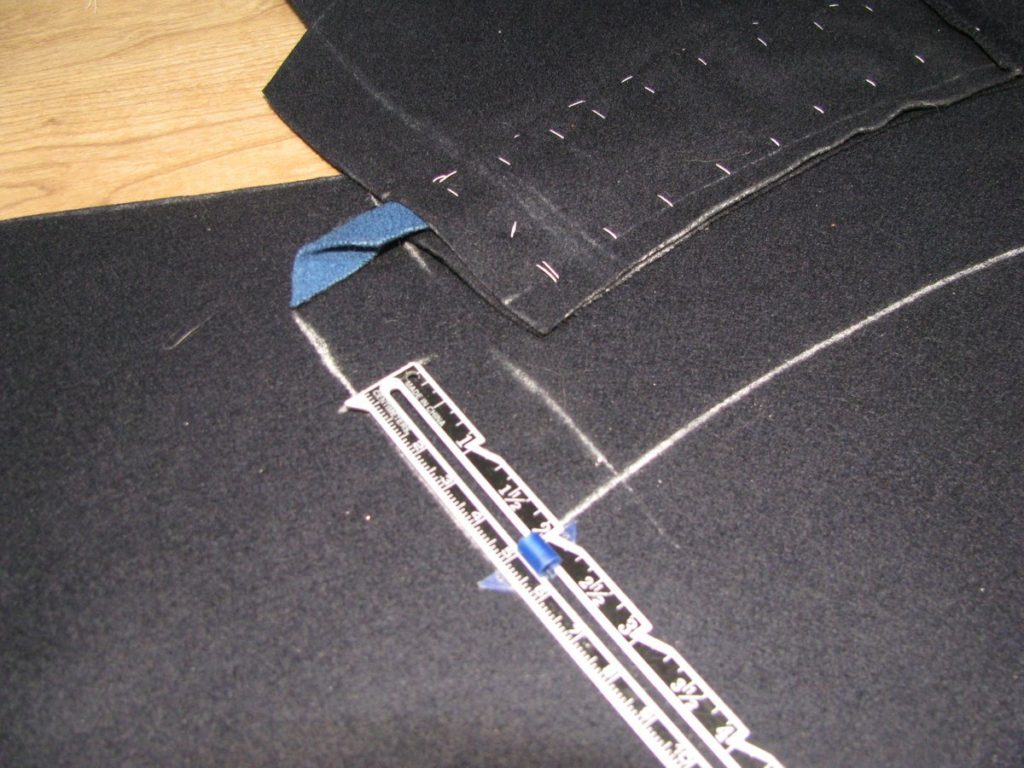

Button Stay Stitching

Along the right side of the coat, from the waist seam, to half an inch below the collar, and half an inch from the edge, chalk a line using black chalk. Top stitch with a machine, or by side stitching if sewing by hand, along this line. This will help bind the layers together, making a sturdier coat, and preventing strain on the buttons.

I prefer to stop 1/2″ from the top of the coat, but I’ve seen some originals where the stay stitching goes all the way to the top.

Setting the Lining

Press the top edge of the sleeve lining over to the wrong side, using a 1⁄4 inch seam. Place shirring stitches along the top of the sleeve head. I only did one row, but feel free to do all three rows if you need more control.

Baste the bottom edge of the lining to the coat body, just covering the stitches holding the sleeve onto the coat.

When you get to the upper sleeve, gather the stitches as you did before, distributing the fullness. Baste in place. Because the lining cannot be shrunk away, you will naturally get a slightly messier looking lining. Try to smooth things out as best you can.

Fell down the sleeve lining to the body, using 10 to 12 stitches per inch. Congratulations, the sleeves are finally done, and we can move on to something more exciting!

Setting the Sleeves

Setting the sleeves can be tricky at first, but there are a couple of steps we can take to make things easier. Due to the amount of ease put in Devere’s sleeves, and the weight of the fabric used, it is difficult to ease in the fabric nicely without some help.

Begin by making three rows of shirring stitches across the inner edge of the sleeve head. These stitches are 1/8 in length, and the rows are 1/8 inch apart. You must keep the stitches aligned between each row for proper gathering. Three rows may seem excessive, but the third row helps lock the gathering in place, making things easier for you. The ends of the stitching should be left free with about 5 inches of extra thread on each end, to ensure it doesn’t slip through at the ends.

At the edge of the center back, mark an ‘X’ in the middle of the small strip near the armscye. Do the same to the back seam of the sleeve. Place these two together and hold them in place with your fingers.

Turn the coat to the inside, still holding these layers together. Make sure the edges of the armscye and sleeve head are even, and then baste the ‘X’s together with a couple of basting stitches.

Holding the layers together with your left hand, ensure that the edges are lined up, and baste down the bottom edge of the sleeve, using a 1⁄4 inch running stitch. You want to baste the bottom half of the sleeve first, so that you know how much to gather for the top sleeve.

Directly at the bottom of the armscye, gather in a very slight amount of sleeve as you baste, about 1⁄4 inch total.

Continue basting until you get to the other seam, where the shirring stitches began.

Now pull each end of the shirring stitches, grasping all three threads at the same time, gathering the sleeve until it fits nicely into the coat. Distribute the fullness so that there are no large folds in the fabric. This step can be fiddly and take a while, but have patience and you will get it. It’s worth the extra time.

When you are happy with the distribution, baste across the top of the sleevehead, fine tuning the fullness as you go. When you reach the other side, where you began basting, stop for a moment, but

don’t cut the thread. Turn the coat to the right side, and check the hang of the sleeve, and that the fullness is distributed nicely. Also check that the rear sleeve seam is centered on the little section of the back piece. This is the time to make any changes necessary.

When satisfied, go back to the inside, and baste around the armscye again, this time alternating your stitches with the previous stitches. This will lock the sleeve in place, while at the same time making the basting stitches easier to remove later.

Place the top of the sleeve head onto a pressing surface so that the

gathered section is visible, and gently shrink away the fullness from the gathering stitches. Press no more than 3⁄4 inch into the sleeve, or you’ll end up shrinking all of the fullness away, and your work will be for nothing.

After pressing you should have a fairly smooth sleevehead, with some fullness visible below the top edge.

Place the sleeve onto the sewing machine, with the coat inside out, and sew the sleeve on with a quarter inch seam allowance. This can be done with a backstitch if preferred, of course.

After sewing, remove all basting stitches from the sleeve area. Some of them may get caught in the stitching, but by picking at them carefully, they’ll all come out eventually. Turn the coat to the right side and check your work. The sleeve should be smooth on top, and slightly raised above the level of the shoulder.

The Sleeve Lining

We’ll now begin constructing and inserting the sleeve linings. These are cut from the same pattern as the sleeve, however some additional allowances need to be made on the seams. On the front and rear seams, add 1/8 of an inch to the seam allowance. At the very top at the sleevehead on both pieces, add 1 inch extra allowance. This is so the sleeve has room for movement, preventing the lining from tearing. It also prevents the lining from pulling on the outer sleeves, producing unsightly folds.

Construct the sleeve just as you did for the muslin sleeve. Make sure you add the inlay at the bottom cuff as per the wool sleeves. Press well. At the cuff end, trim off a half inch from the bottom, then turn under another half inch seam allowance. This will line the bottom of the lining up with the upper edge of the cuff facing, just covering the cross stitches.

Turn the wool sleeve inside out, and the sleeve lining right side out. Insert the sleeve lining onto the wool sleeve, wrong sides together, and pin the two together at the bottom of the rear seam, just above the inlay area. This will help you align the rest of the sleeve sections together.

Make sure the lining is falling smoothly over the entire sleeve. You may pick up the sleeve and lining by the cuff and shake slightly to help distribute the fabric properly.

Starting at the side with the inlay, baste from the bottom of the sleeve lining, up along the edge of the inlay, and along the top edge of the inlay, folding the fabric under neatly as you go.

Now baste across the bottom edge, which should have already been pressed under. The lining should just cover the cross stitching by about 1⁄4 inch.

Continue basting across the bottom until you get to the area where the extension on the facing begins. At a location about 1⁄2 inch below the top of this extension, make a cut in the lining at right angles to the edge of the lining, and about 1 3⁄4 inch wide. The cut should be a bit shorter than the width of the facing extension.

Now fold under this section of lining, exposing the buttonholes underneath, and baste down, stopping at the end of the cut you made.

The lining is now felled down with white cotton thread at this point, using 10 to 12 stitches per inch. Using the white thread will help hide the stitches, making them almost invisible. Begin sewing at the end of the cut lining, down to the bottom of the cuff, across the bottom, and up the sides and top of the inlay area. When sewing the section near the inlay, be careful not to let the stitches show through to the right side, as it is only one layer.

Now we are able to finish off the sleeve vent area. Align the inlay area of the sleeve over the buttonhole section with about a 1 inch overlap. Baste in place to keep in from moving.

Stitch the top of the inlay down to the vent extension area on the other half of the sleeve. This is done using a back stitch. I use black silk thread for this for a little extra strength. Again, don’t let the stitches show through to the right side. Sew from the edge of the inlay, diagonally up towards the seam area. It’s okay if the stitches go through the lining a little. These will be covered up.

Fold the unfinished flap of lining under, and baste it in place. This should cover the stitches you just made, and provide a nice finished look to the sleeve lining. Fell this down with white thread as before.

The section where the inlay meets the lining is potentially weak, and could tear the lining after extended use. To help prevent this, make a simple bar tack by making 5 or 6 stitches in place, just below the level of the lining. This should catch the edge of the inlay on the top, and the top layer of the sleeve facing below. I like to use buttonhole twist for extra strength here.

At this point, the sleeve vents are completely done, save attaching the buttons. Remove all basting stitches and turn the sleeve to the right side.

Again, shake the sleeve gently to make sure the lining is laying correctly on the inside. Based through the outer sleeve, catching the lining underneath to hold it in place.

Finishing the Sleeves

Turn the sleeves so they are laying wrong side up on the table. Trim the seam allowance from the seam that is holding the facing to the sleeve as shown. This will allow the facing to turn with as little bulk as possible.

Baste in a piece of linen about 5 inches long by 2 inches wide. This should be inserted next to the strip of vent piping, and will give additional strength to the buttonhole area.

Turn and baste the sleeve facing over, basting along the front edge, and up along the extension on the side. Press well.

Trim a very slight amount – no more than a quarter inch – away from the edge of the facing directly above the vent piping. Fell down the vent to the piping, making sure the machine stitching holding the piping down is completely covered in the process.

On the other end, the edge is trimmed if necessary to make everything flush, and then stitched closed through all layers using buttonhole twist and and a buttonhole stitch for strength.

Turning to the wrong side of the sleeve again, cross stitch the inner edge of the facing to the sleeves, being sure to not pull the stitches too tightly. If you do, a fold of fabric will be visible on the right side of the finished sleeve – something that you want to avoid.

Now is the time to add two buttonholes to each cuff, on the piped side of the sleeve. Both buttonholes should be a half inch from the edge. The lower buttonhole is centered between the piping and the bottom of the sleeve, while the upper buttonhole is placed just high enough to avoid running into the piping of the chevron by about half an inch. Work the buttonholes as described in the buttonhole module. The lower buttonhole can be tricky a first, as it has to go through three layers of wool plus the linen layer. If you have to, pass the needle all the way through the hole first to make things slightly easier. With experience, you’ll find this is not necessary though.

After all that work, the sleeve cuff is finally done.

Line up the rear seams of each sleeve, right sides together. Baste and sew from the top of the seam, to just 1⁄4 inch beyond the edge of the sleeve inlay, as shown. Press well, using a sleeve roll or tailors ham inserted into the sleeve. This is sometimes tricky to press correctly due to the nature of the curved sleeves.

Vent Piping

Now we come to one of the trickiest places to sew on the entire coat. First chalk a line 3/8 inches away from the edge of the sleeve, on the chevron side.

Baste a 5 inch long piece of piping onto the sleeve at this point, lining the folded edge up flush with the chalk line.

Sew a 1⁄4 inch seam, counting from the edge of the sleeve, not the piping. It’s very difficult to sew over the point where the two pipings meet, being about 7 layers thick. Be sure you are using a size 100 needle for this. Once you get over that spot, it gets easier again.

On the wrong side, trim back the sleeve over the piping a little, tapering back out to it’s original width at the end of the piping. Do the same with the middle layer of piping.

This small strip of piping needs to be pressed to the underside of the sleeve now. Due to all the layers, this can take a few tries. Press from both sides to set the stitches well, then fold the piping under, and press well with a heavy weight if you have one. You’ll still end up with a slight bump no matter how well you press, but these are present on originals as well.

Cuff Facings

Place the sleeve face down on the cloth, making sure the grain is aligned. Draw a construction line if necessary to get a good alignment. Trace around the bottom, and the sides to just where the piping stitch line is.

For me, this happens to be two inches high. Draw a line indicating the top of the facing at this level, all the way across. When you get to the right side, strike upwards for 3 inches, two inches from the edge. Then close the top of the facing. Make the corners round, as shown. The height of this side extension piece should be equal to the inlay on the other side.

Cut out both facings, and check for fit if desired.

Turn the sleeve wrong side up. At the bottom of the cuff, mark a line 3/8” from the edge, all the way across.

Trim only the top layer, which is the sleeve layer itself. The cuff beneath is untouched by the scissors.

Place the cuff piece, right sides together, onto the sleeve, being sure that the side with the extension is on the same side as the chevron. Baste together along the bottom edge.

Sew a quarter inch seam, sewing the facing to the cuff piece. The sleeve itself should just miss these stitches by 1/8 of an inch.

Assembling the Cuffs

Place the cuff on top of the sleeve, with right sides of both facing up. The chevron should be on the opposite side as the inlay on the sleeve. Baste along the bottom, keeping 1⁄2 inch away from the edge.

Continue basting along the top edge of the cuff, just behind the piping. Try to get as close to the edge as you can without actually catching the strip of piping that’s showing.

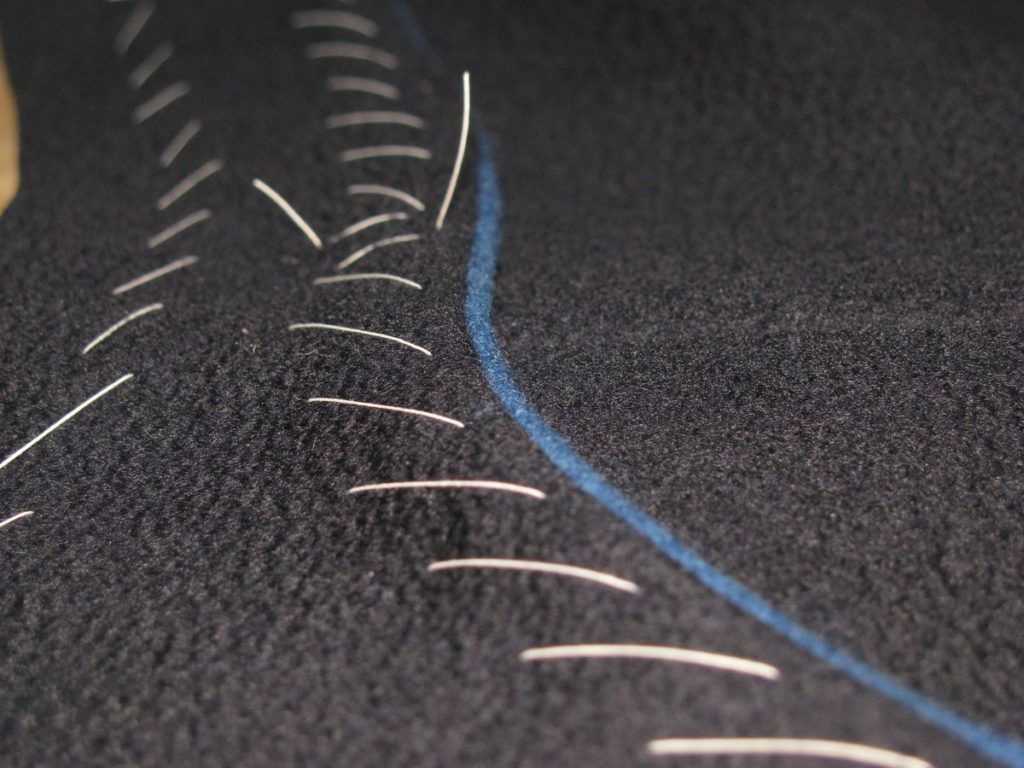

Here comes the tedious part, more side stitching! Using 10 – 12 stitches per inch, side stitch the piping to the sleeve, using the same method as the collar. If you need to save time, you can use a machine and zipper foot, but I find the side stitching gives superior results.

Here’s a photo of the underside after the side stitching. All you see are little pinpricks from the stitches, securely holding the piping in place.

Cuff Piping

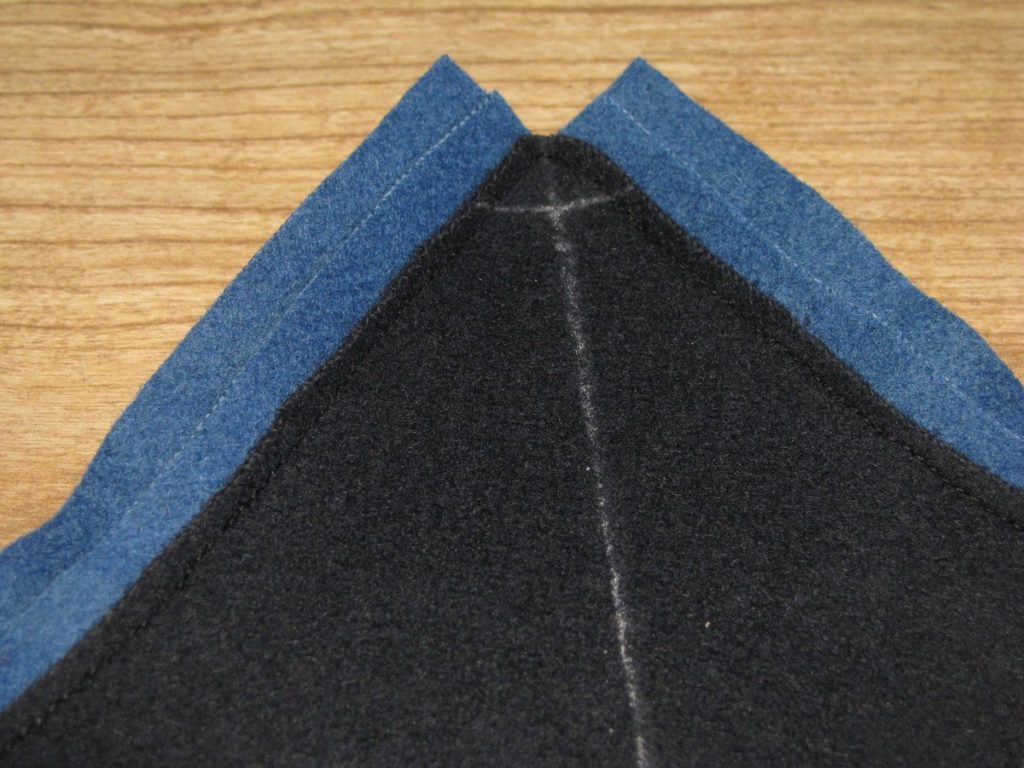

Dealing with the point of the chevron needs some special consideration. First, you must trim off the piping, using an angled cut. The narrow end near the tip should be about 1/8 inch away from the stitching.

Press the cuff well from each side to set the stitches. I then like to press the piping over on both sides of the tip, saving the tip for last. The process is the same as for the collar.

To press the point, I like to turn the cuff over so that the right side is up, and roll the piping at the tip under with a finger. This is followed directly behind by the iron, keeping the tension so that the piping stays underneath. Don’t worry if it takes a few tries, you’ll get it soon enough.