Month: March 2020

Drafting the Collar

On to drafting the collar! I recommend not even starting this step until you have made a successfully-fitted toile, as it will only add more complexity to figure out the collar in addition to the usual fitting issues.

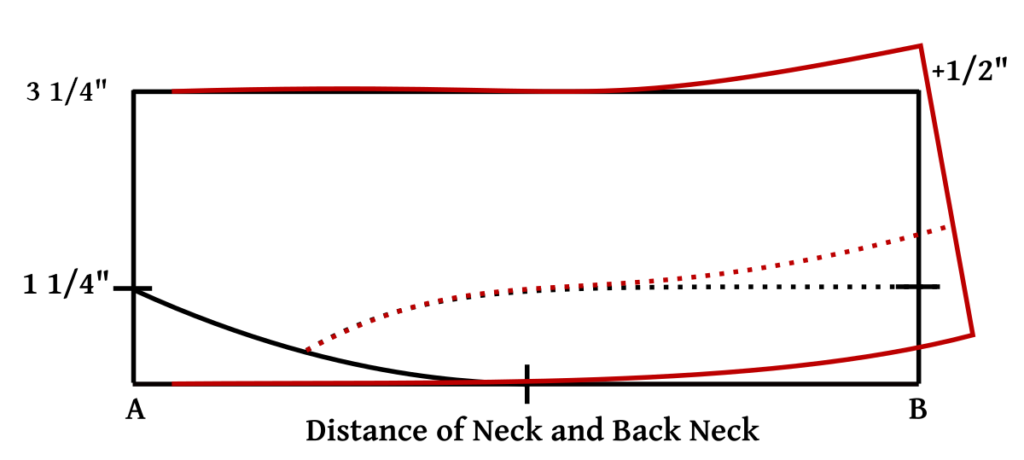

Before drafting, you need to measure the neck of your paletot pattern carefully – I usually stand the tape measure on its side so I can get around the curves more accurately. Measure from the point you made two graduated inches from the front of the coat, along the neck, and the back neck, not including seam allowances.

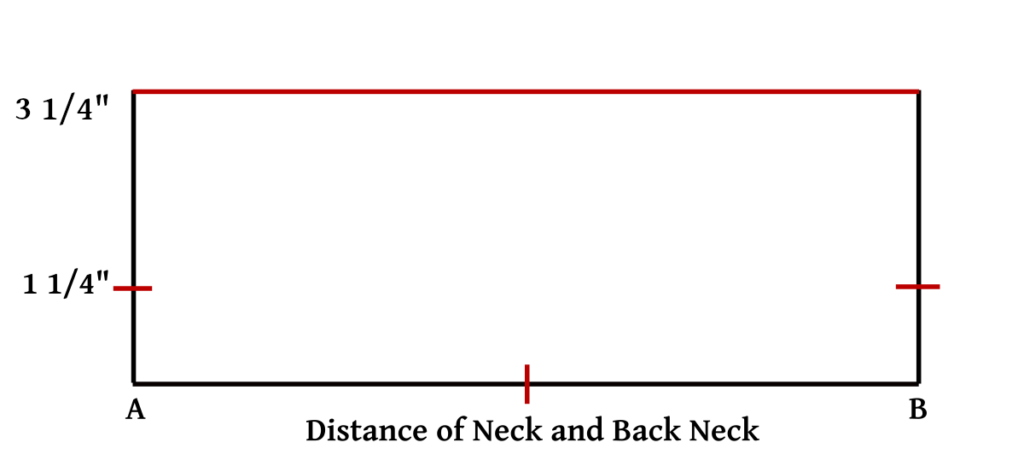

To begin drafting, draw a horizontal line and mark two points on either end equal to the neck measurement you just took.

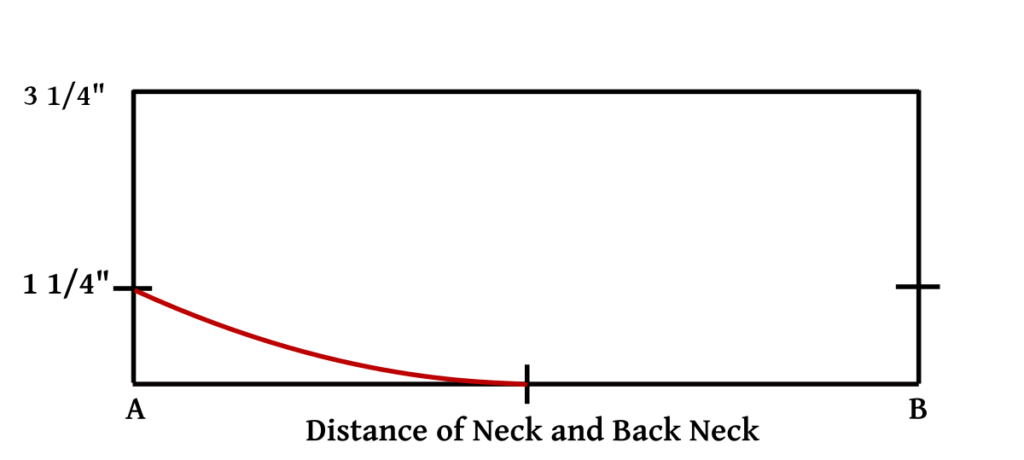

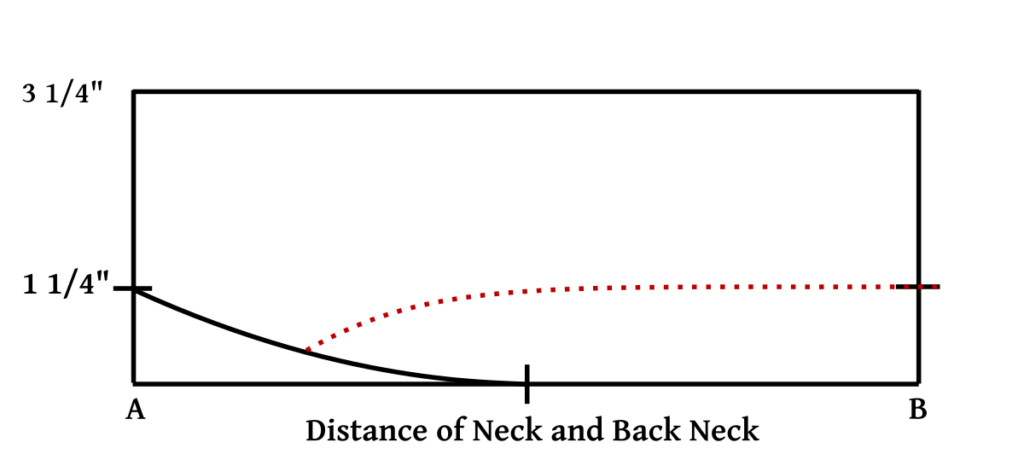

square up at either end and mark the distances 1 1/4″ and 3 1/4″ on each side. You can use graduated inches here, but if you’re making a larger coat size, then I’d advise sticking to normal inches.

Draw a nice curve from the center bottom to the 1 1/4″ mark.

Draw the roll line next, at first parallel to the bottom of the collar, then curving downwards to intersect about halfway between the bottom curve of the collar. Note, I’m just using the dotted line for clarity, use a solid line for your own.

This next step is optional, but I find it gives a better fit to the linen collar, since we won’t be doing any pad stitching for shape as in a normal coat.

First, raise the point on the right from 3 3/4″ to 4 1/4″. Then redraw the top seam of the collar with a curve gradually straightening out near the center.

Next, square down from 4 1/4″ to get the new center line of the collar. We need to square down here in order to prevent getting an ugly ‘v’ shape to the back of the collar. This line should be equal in width to the left line, 3 3/4″.

Finally, redraw the bottom of the collar with another curve.

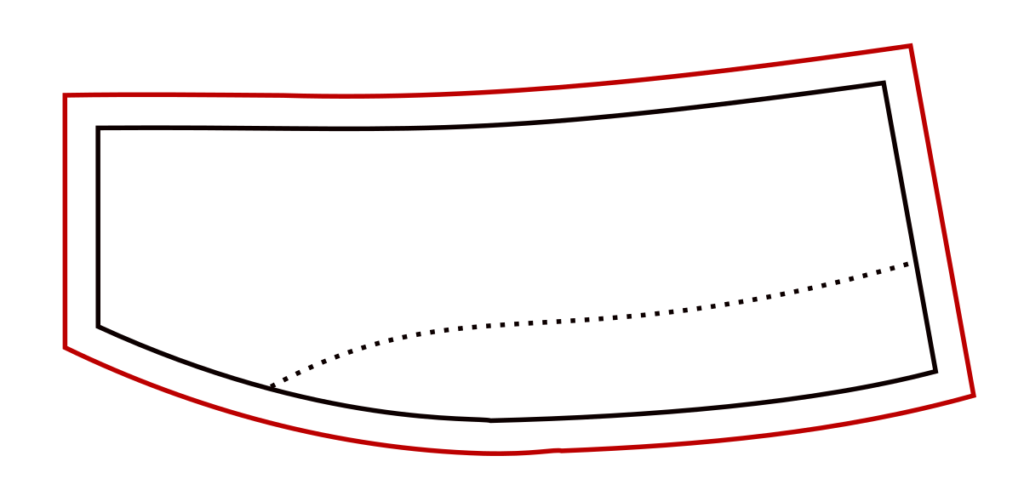

When you are happy with the shape of your collar, add 1/2″ seam allowance all around and cut it out.

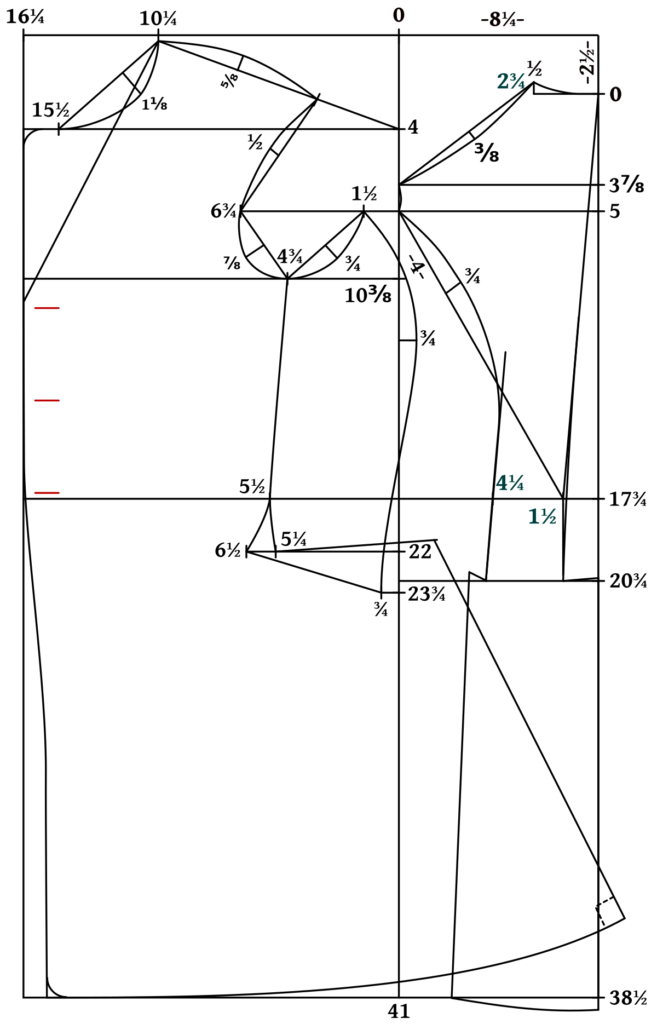

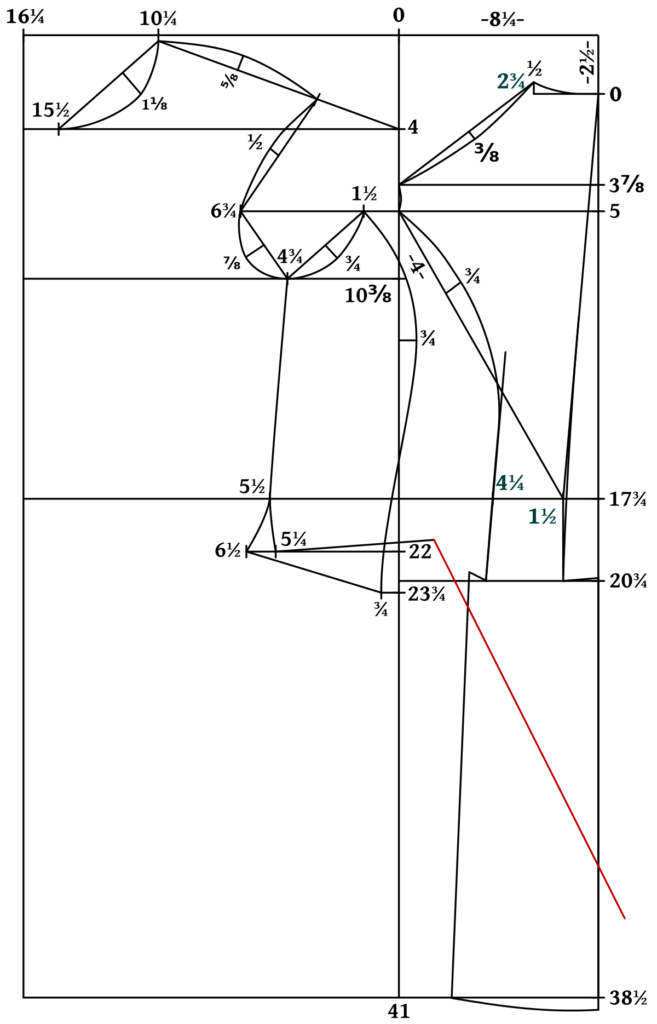

Drafting the Sleeves

I highly recommend not drafting the sleeves until you are happy with the fit of the coat and collar.

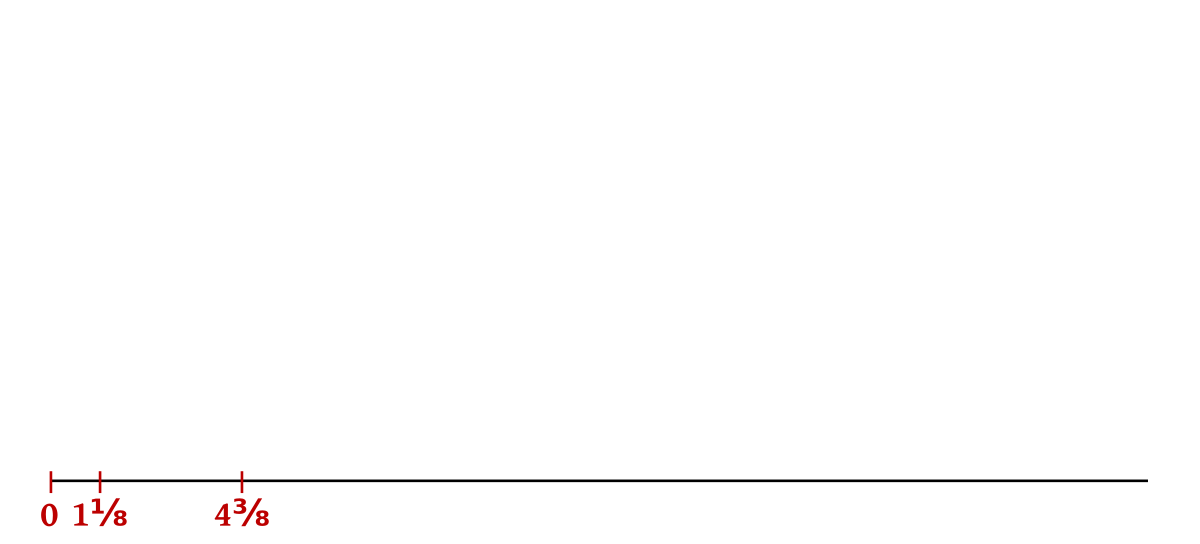

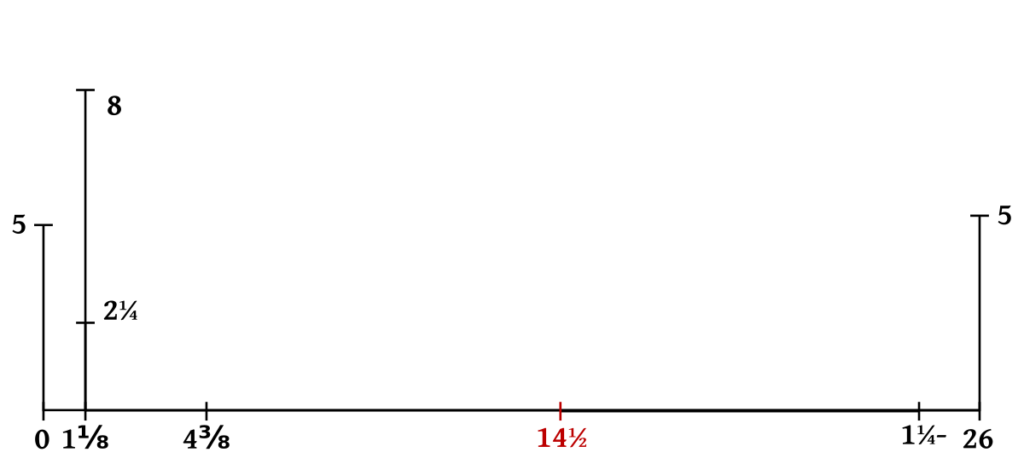

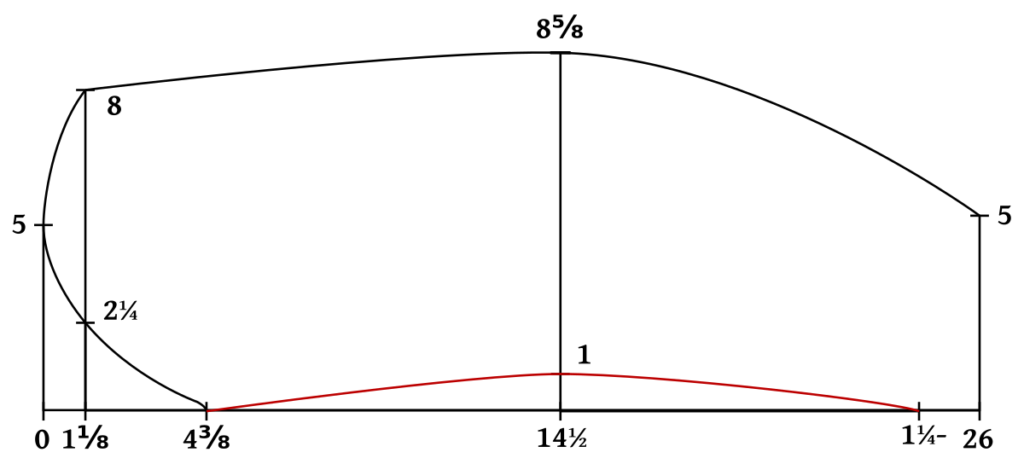

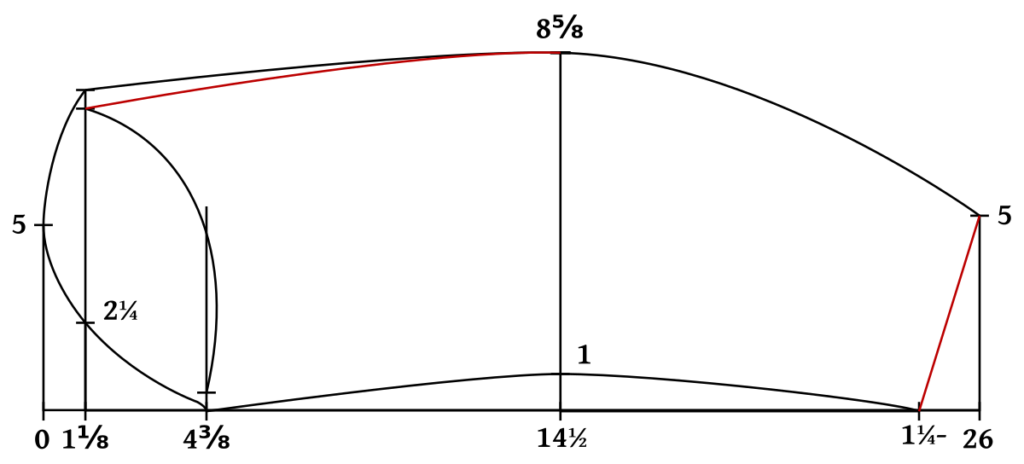

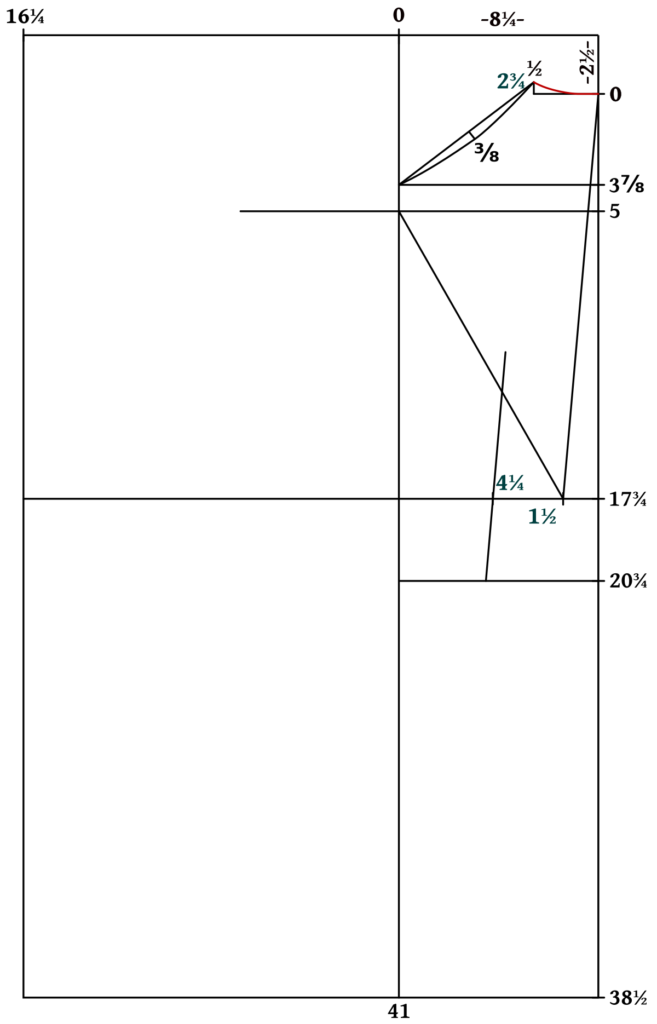

To begin, draw a horizontal line and mark out the following points from 0 with your graduated ruler (according to your breast size still).

Square up from point 5 graduated inches from point 0. This gives the top of the sleeve head.

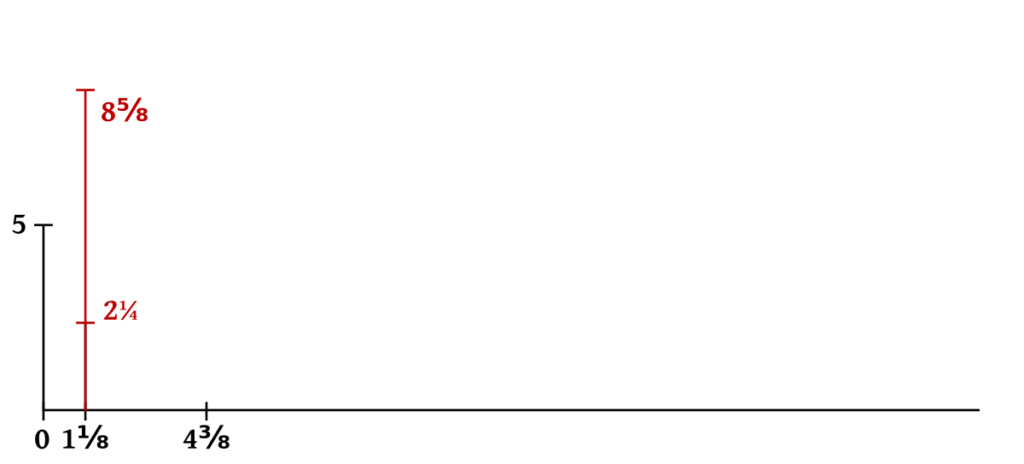

Square up from 1 1/8 and mark the points at 2 1/4 and 8 5/8. This latter number really dictates the width of the sleeve head, so if it ends up too big later, this is the area you’d want to adjust.

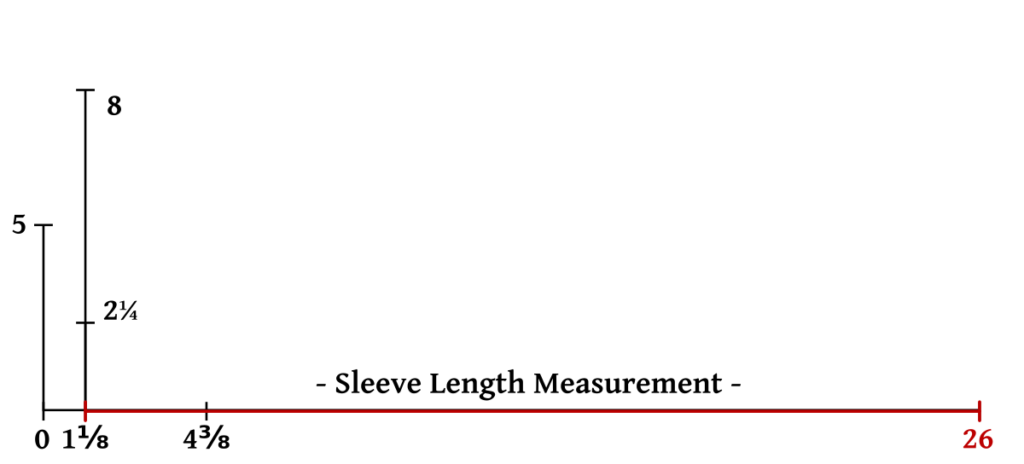

Now mark 26 graduated inches, measuring from the 1 1/8 mark, indicating the length of the sleeve. Definitely compare it to the sleeve measurement you took, and if there is a discrepancy, go with your actual measurement, not the graduated one.

N.B. I made a mistake with the draft and you’ll see point 8 listed in most of the following diagrams. It should indeed be 8 5/8.

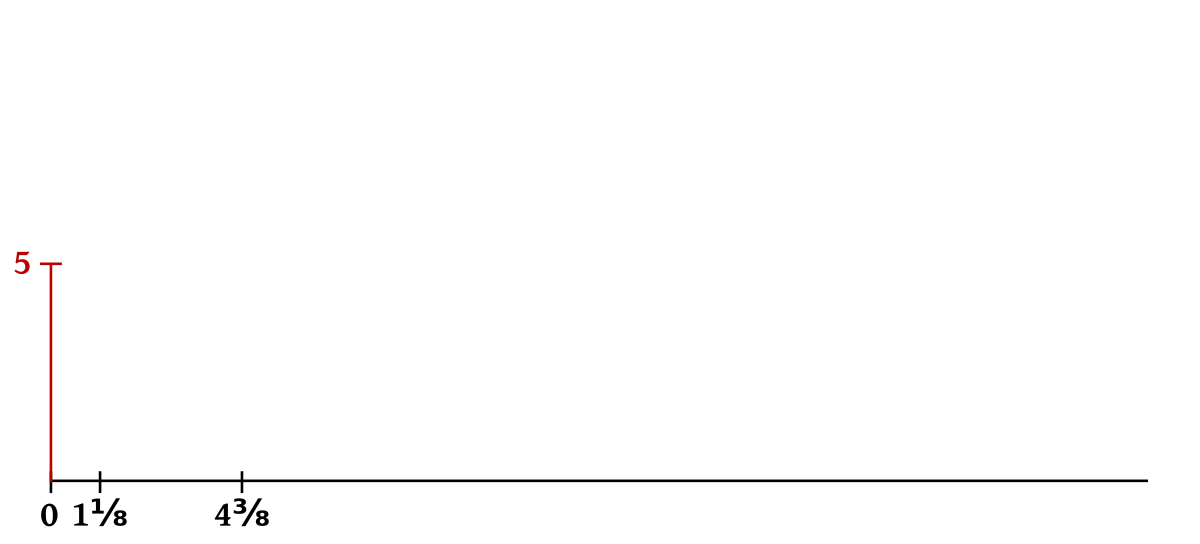

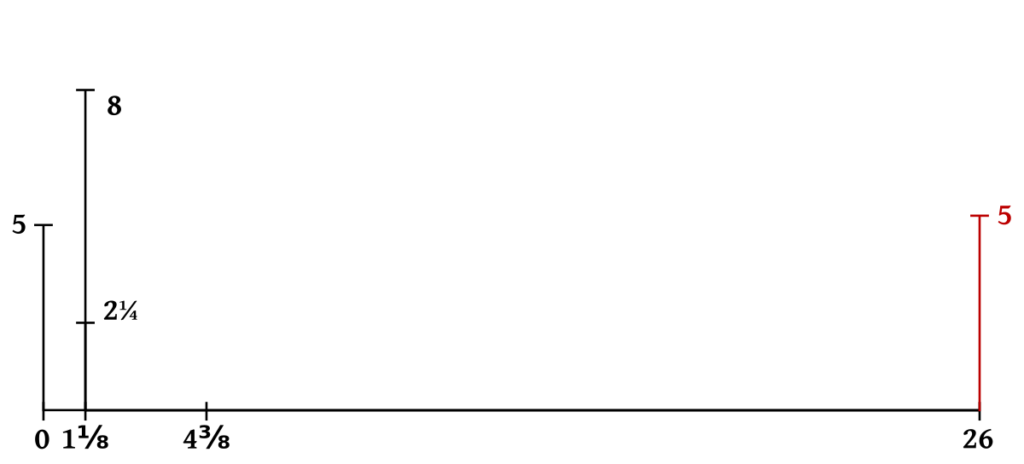

At the cuff end of the sleeve, square up 5 graduated inches for the width of the cuff. Generally, I wouldn’t go more than 5 1/2 regular inches except for the thickest of wrists.

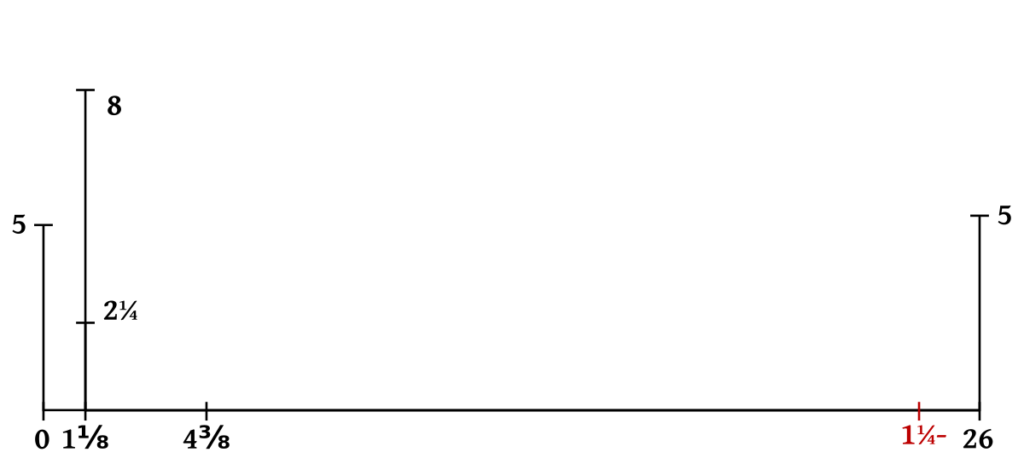

Measuring from the cuff, mark a point at 1 1/4 graduated inches.

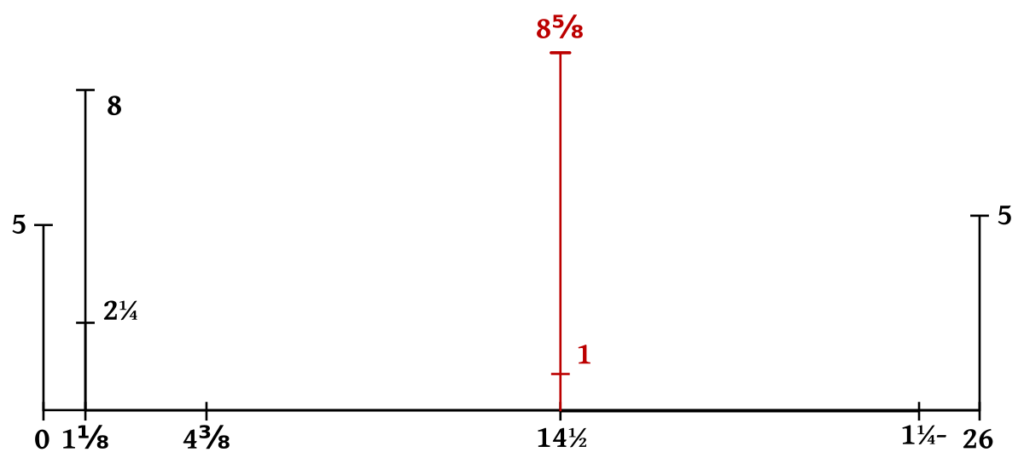

Now for this step, the graduated measure at 14 1/2 is often incorrect, especially if you have used your own sleeve length measurement. Basically, find the center between 1 1/8 and 26 and mark that point.

Square up and mark 1 graduated inch for the curve of the sleeve, and while 8 5/8 is recommend, I’d actually go with more of a 9 5/8 for the 1860s period, to give more of that ‘ballooned’ sleeve look. It may take some experimentation on your part to get just the right curve.

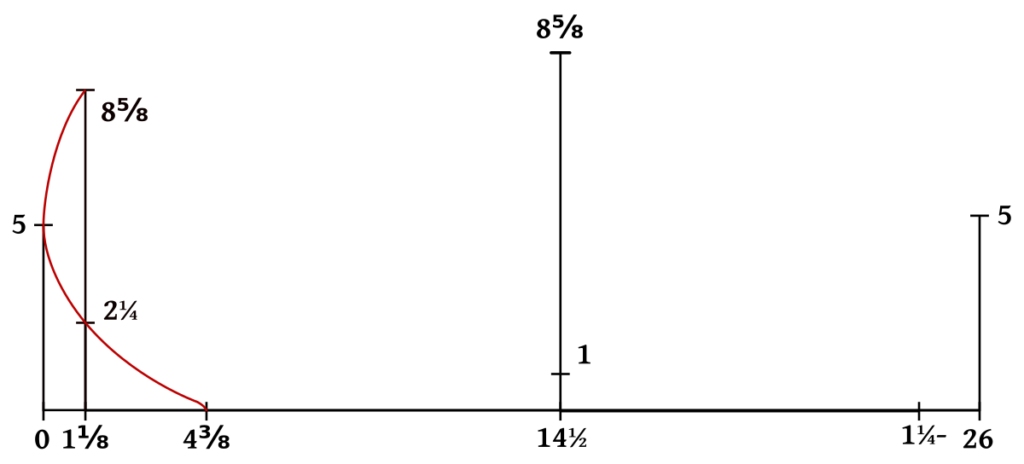

Now it’s time to draw in the curves and outlines. Start with the top of the sleeve heard, drawing a nice curve connecting 8 5/8, 5, 2 1/4 to 4 3/8. As your line is approaching 4 3/8, aim a little high and then curve in the opposite direction, kind of like an ‘S’, to make forming the seams later on a bit easier.

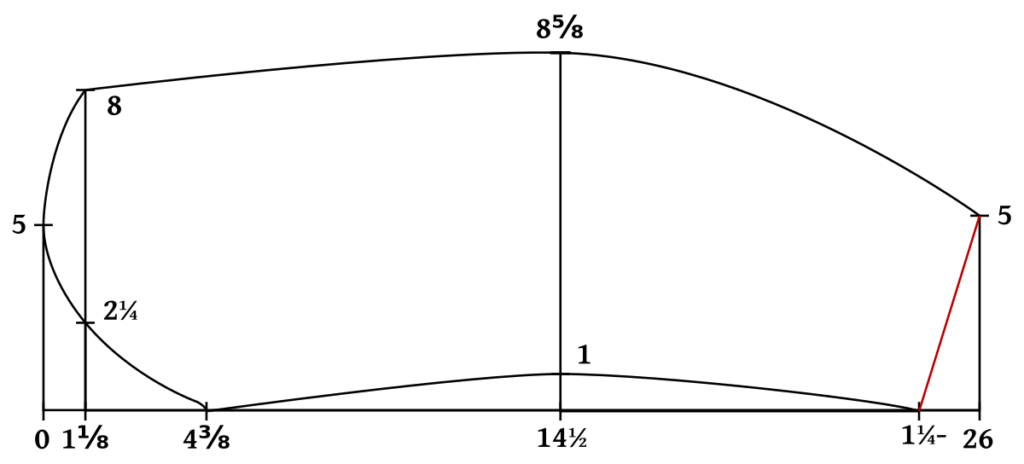

Draw the rear seam for the top sleeve. Again, you may need to adjust the curve at 8 5/8 to make it a little fuller.

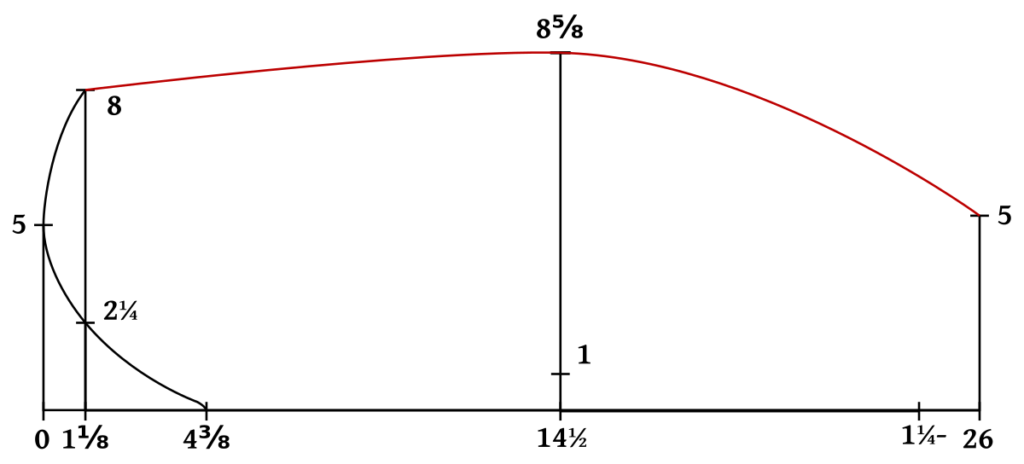

Draw the front sleeve curve from 4 3/8, through 1, to 1 1/4.

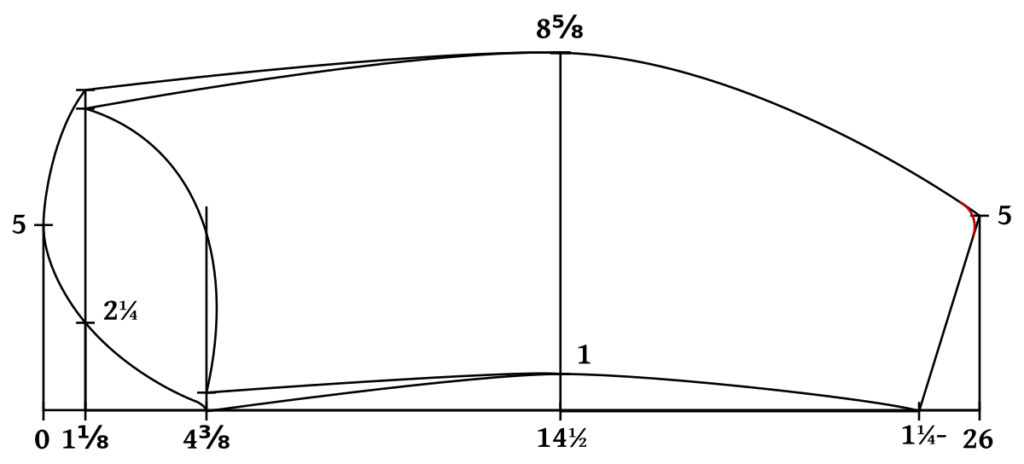

Draw the cuff with a diagonal line from 1 1/4 to 5. This completes the top sleeve.

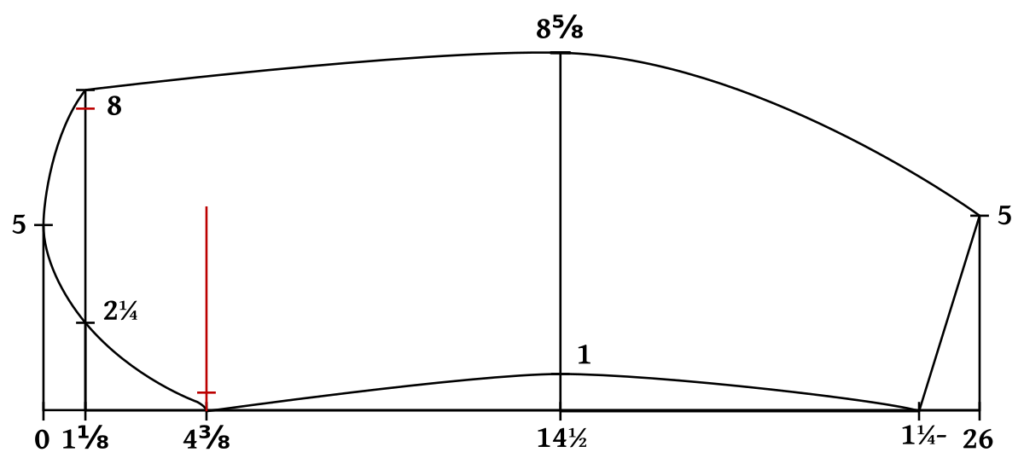

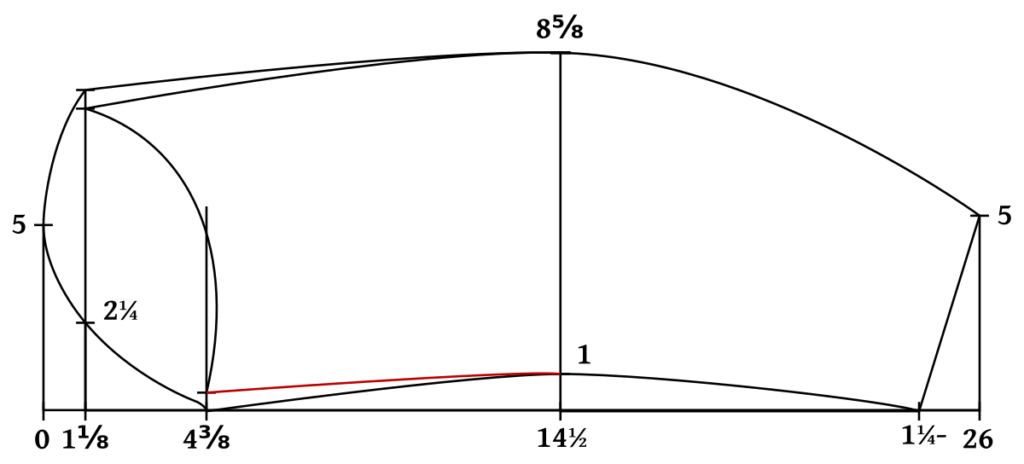

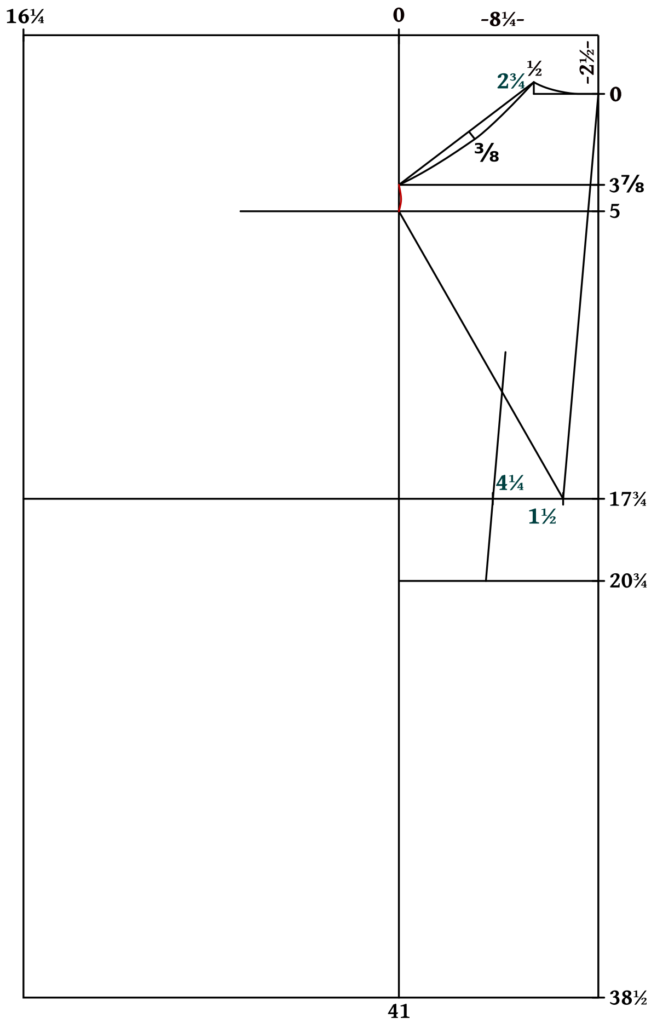

Square up a line from 4 3/8, the length doesn’t really matter much. Mark 5/8 inch down from the point at 8 5/8 (8), and then 3/8 up along this new line from 4 3/8.

Draw a curve for the undersleeve from 8 to 4 3/8, passing by the construction line to a depth of roughly 1/4″, as shown.

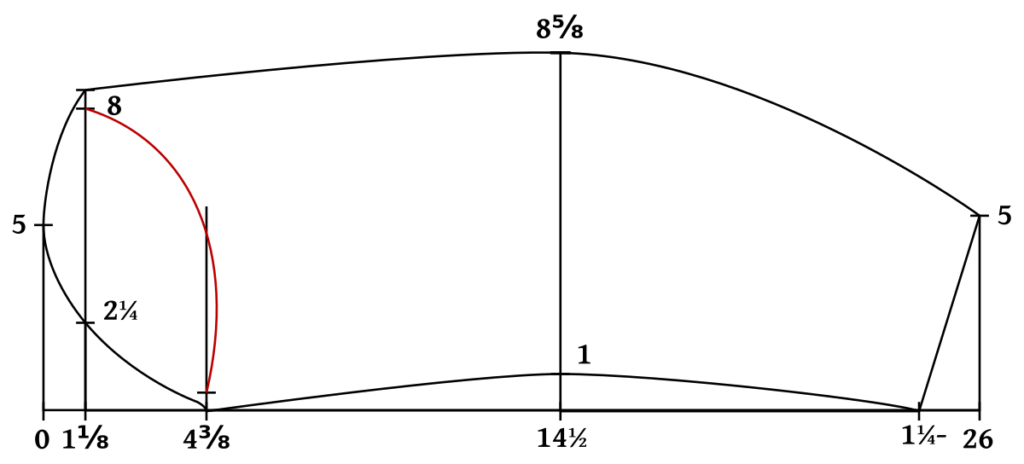

Draw a line from point point 8 tapering into 8 and 5/8 to finish the rear undersleeve seam.

Do the same for the front seam.

Before completing the draft, curve the rear seam at the sleeve cuff at 5 with the same curve you did on the coat neck and hem.

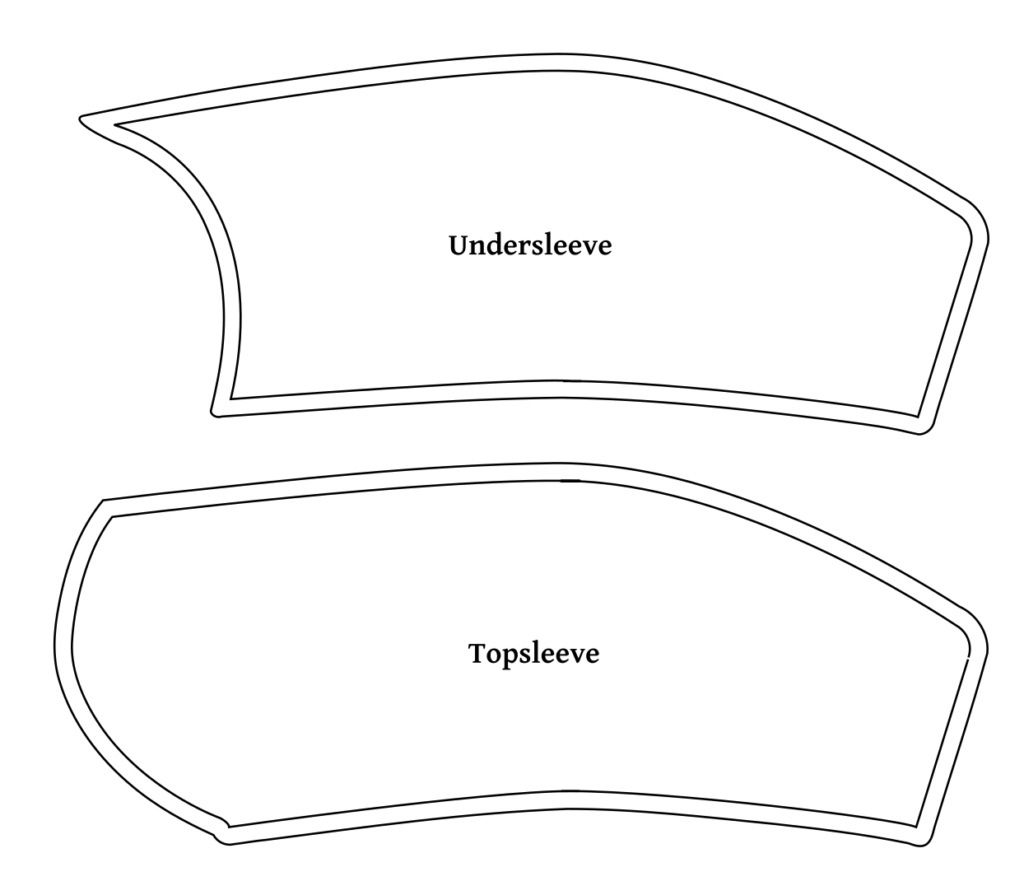

Finally, trace each piece on to a fresh sheet of paper to separate the patterns, and add a 1/2″ seam allowance all the way around.

Draft Details

There are just a few details left on the draft before we are ready to cut out a pattern.

The first is adding a roll line to indicate where the lapel begins. On the original coat, this seemed to start about one inch below the chest line or armscye. Connect it to the top of the shoulder point as shown.

Next, add the buttonholes to make finding their position much easier later on. There were three buttonholes on the original. The first should be located 1/2″ below the bottom of the lapel. The bottom should be on the waistline (I put mine a 1/4″ above just so you could see it more clearly. And finally, the third and middle buttonhole should be spaced equidistantly between them. All of the buttonholes should be 1/2″ from the edge.

This is not in the original draft, but makes sense and also makes life a lot easier. At the top of the skirt near the back, raise the back point up 3/8″ to match the pleat on the back piece, redrawing the lines as necessary. The total width of this is 7/8 graduated inches like the back.

Another little detail to add is a mark two graduated inches from the center front along the neck line. This indicates the end of the collar, which you’ll measure from later. Transfer this to your fabric pieces when the time comes.

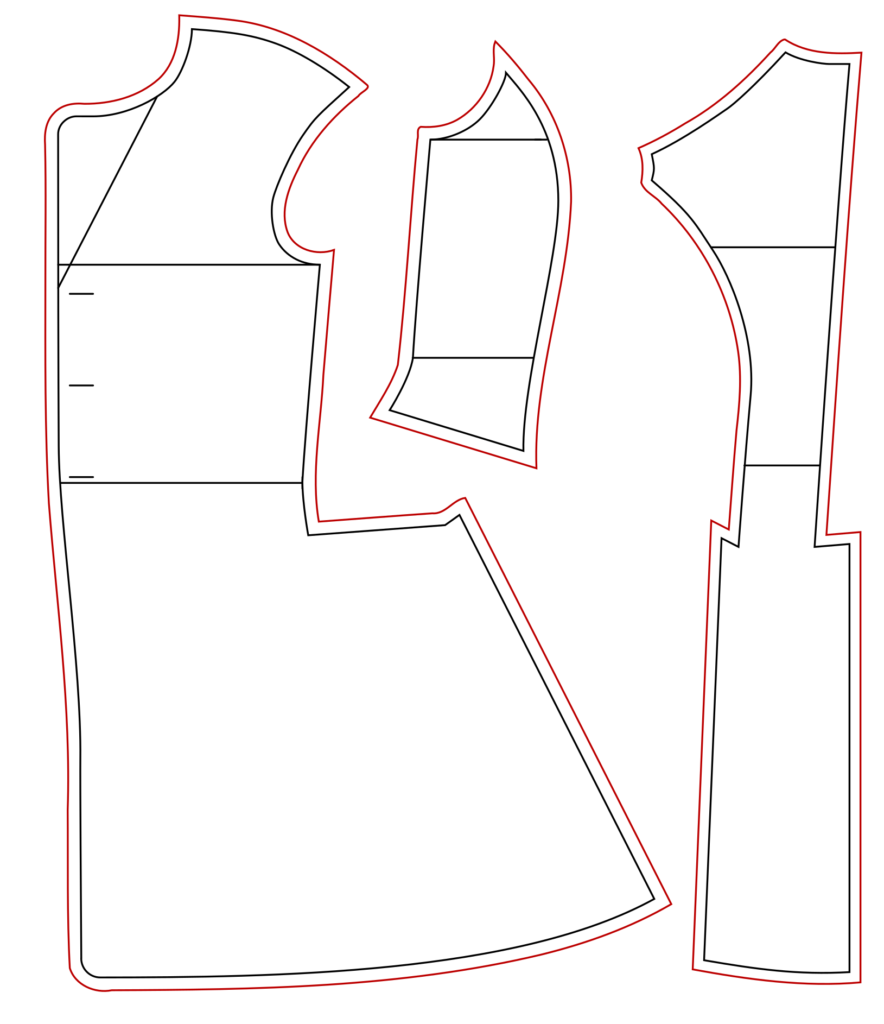

Finally, you may have noticed that all of the pieces are overlapping each other. You’ll need to separate them in order to make them usable. I like to trace out the back and side body onto separate pieces of paper, but you might transfer the front as well in order to preserve the original pattern draft in its entirety for potential alterations later on.

Typically I can see through the paper so I just trace it that way. They also make pattern tracing wheels you could use, or perhaps a light table. Just do what works for you.

After the patterns are traced out, using a quilting ruler, add a 1/2″ seam allowance all the way around each pattern piece. This is necessary for the type of seams we will be using to piece the paletot together.

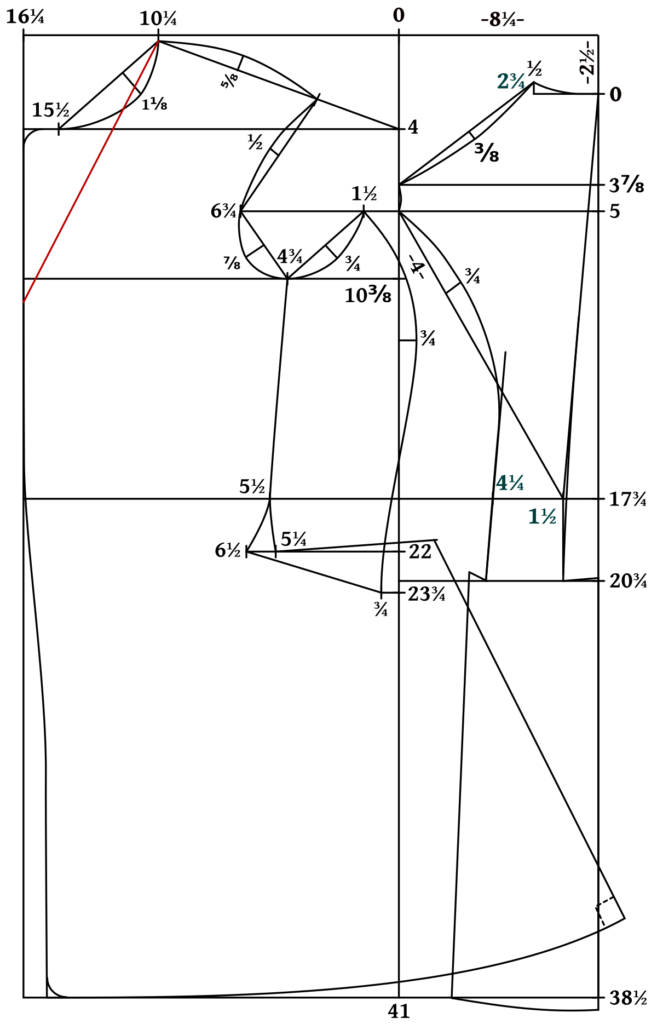

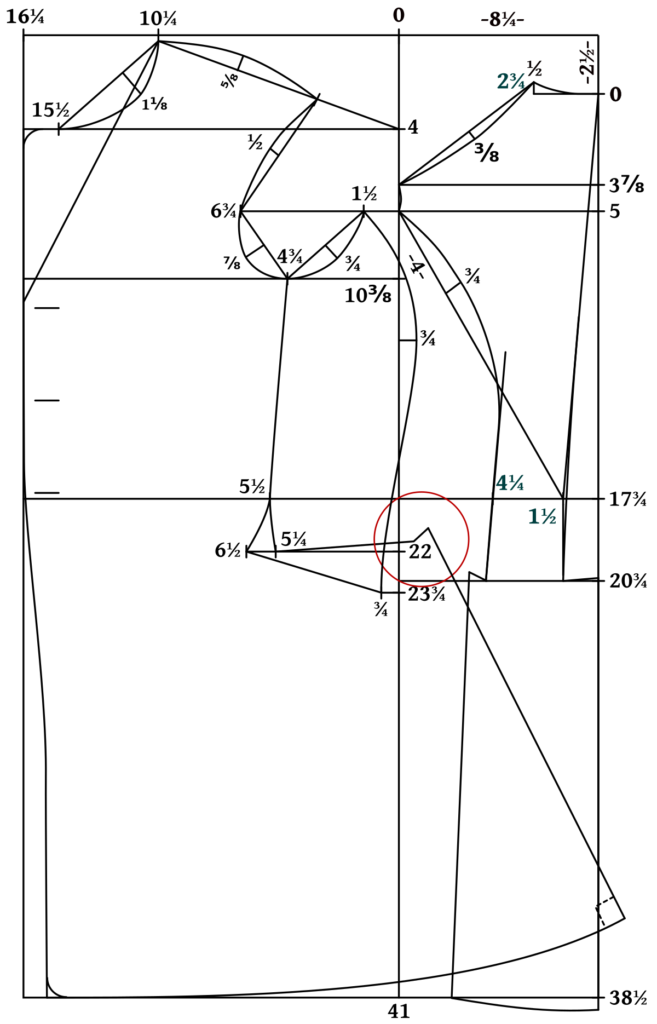

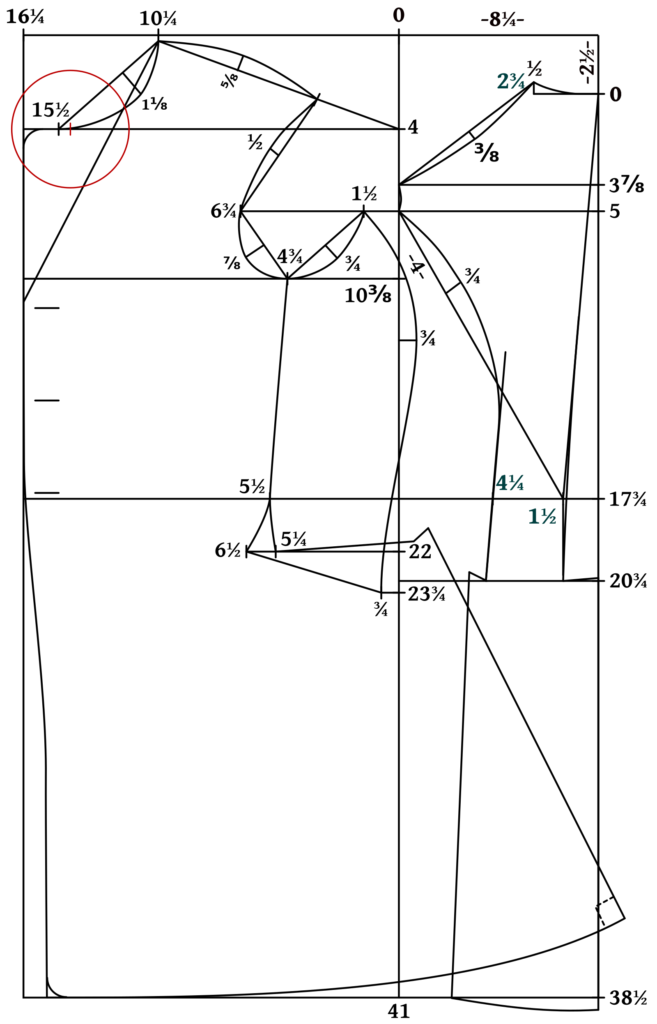

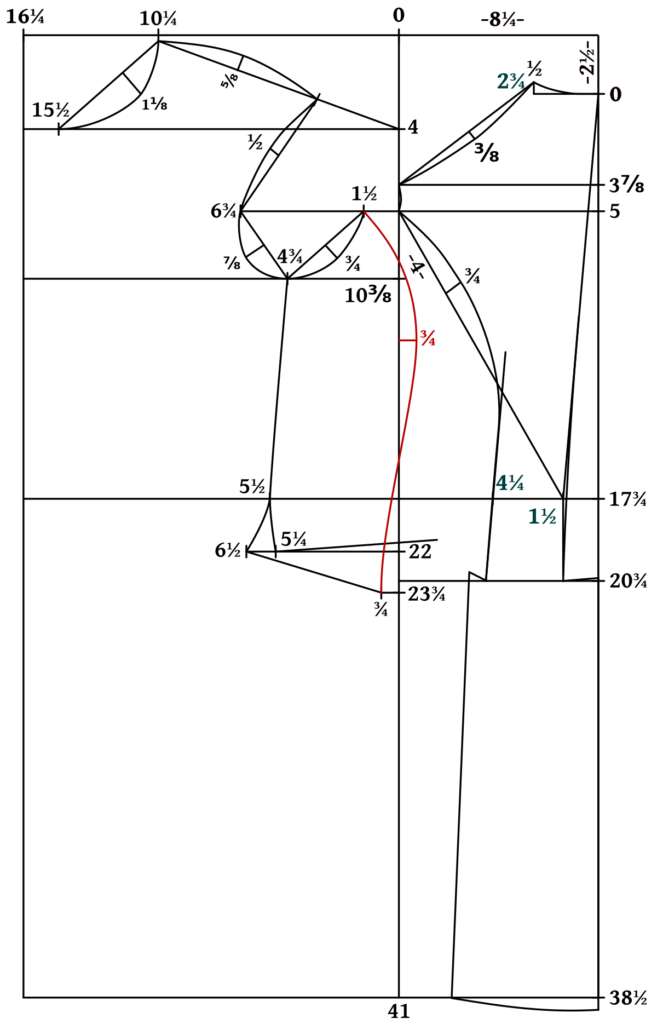

Drafting the Front

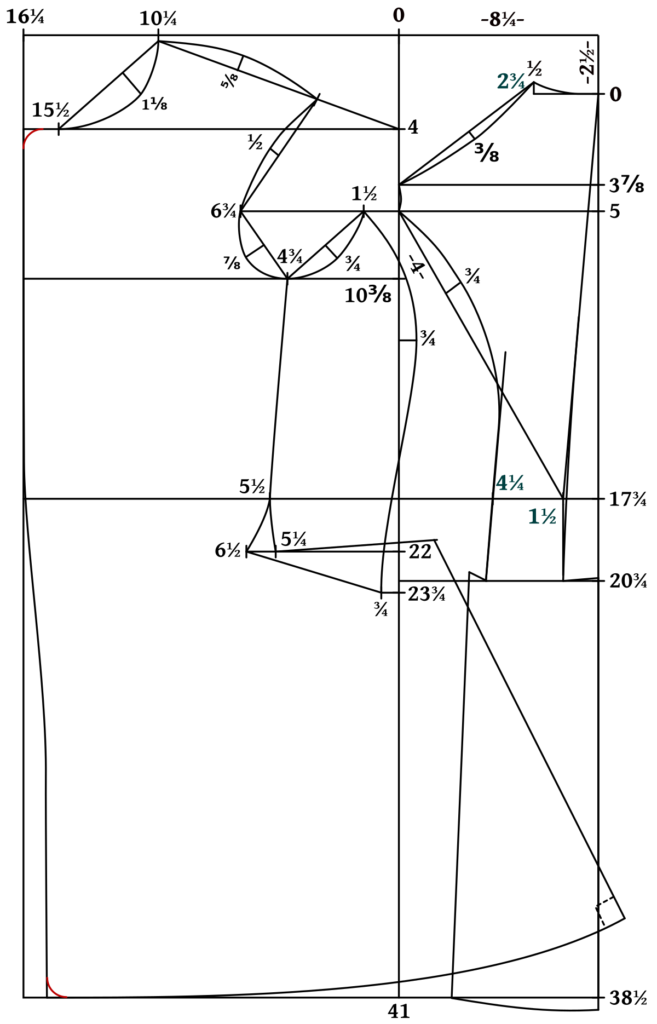

Now that the back is complete, we can move on to the front of the draft.

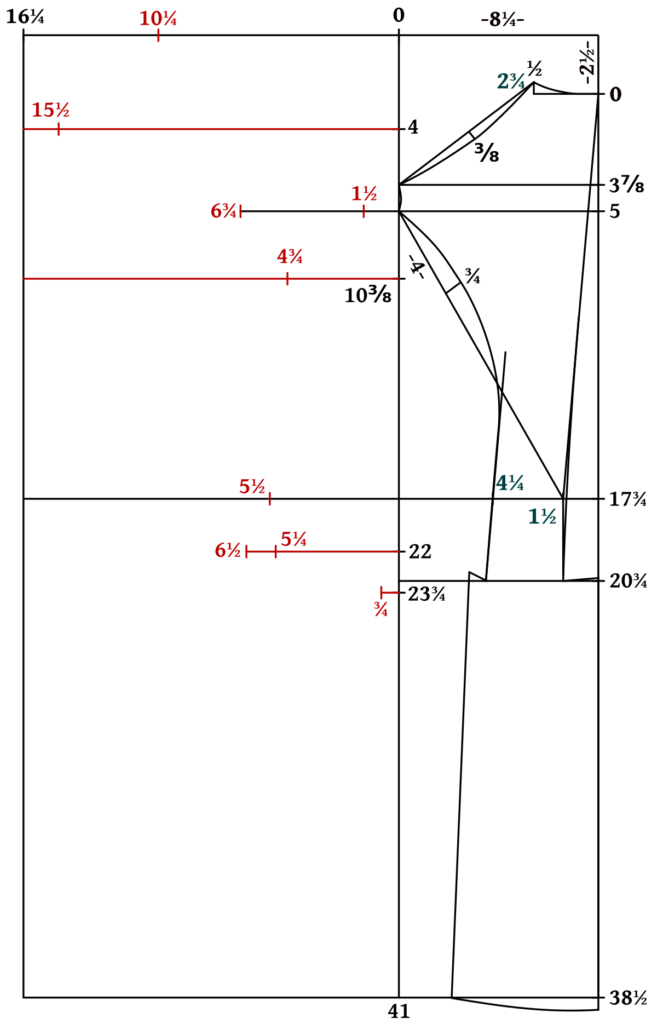

Begin by marking the following on the construction line from 0:

4 for the shoulder angle.

10 3/8 for the bottom of the scye.

22 for the top of the skirt.

23 3/4 for the bottom of the side piece.

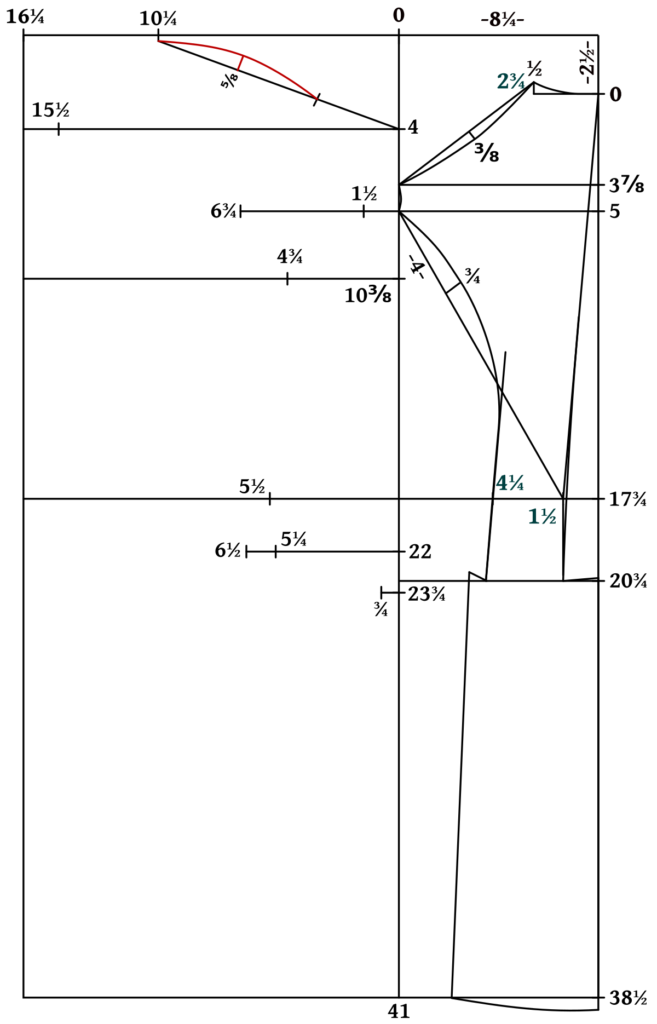

This is somewhat of a big step, but just mark one thing at a time down the list:

10 1/4 for the shoulder point. Also square down 1/4″ here (not shown).

15 1/2 for the neck point.

1 1/2 for the top of the side body.

6 3/4 for the armscye width.

4 3/4 for the bottom of the armscye.

5 1/2 for the position of the side seam.

5 1/4 and 6 1/2 for the ‘spring’ at the hips.

3/4 for the bottom of the side body.

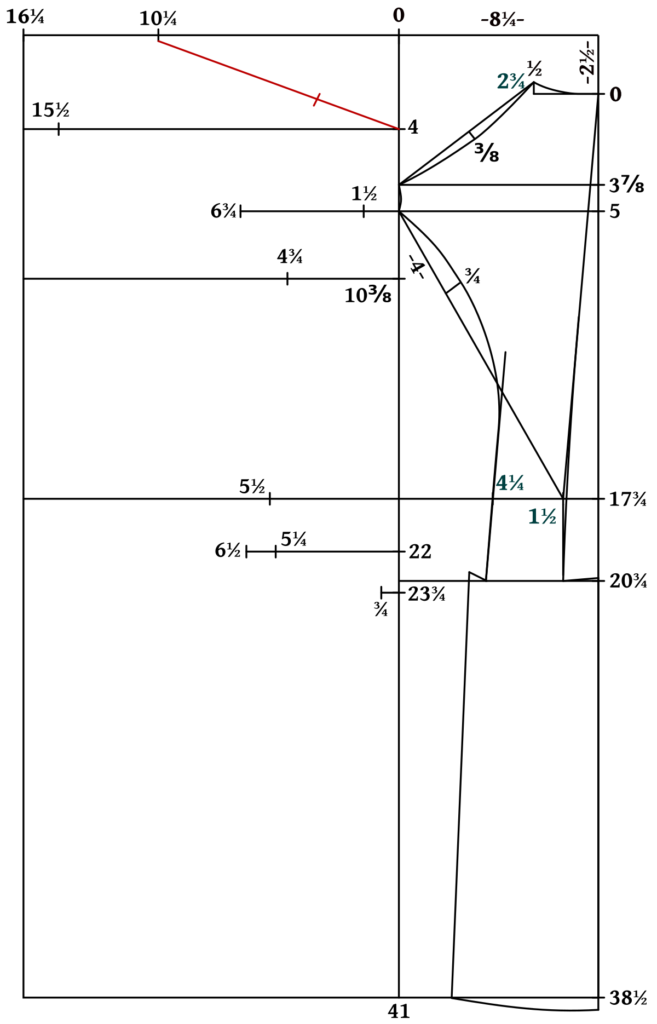

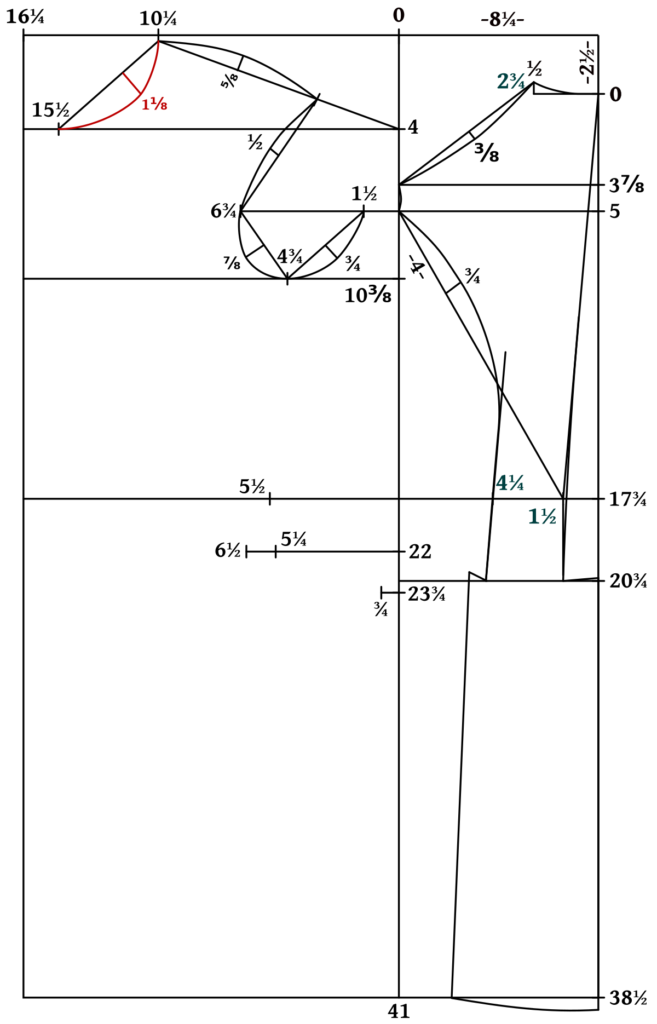

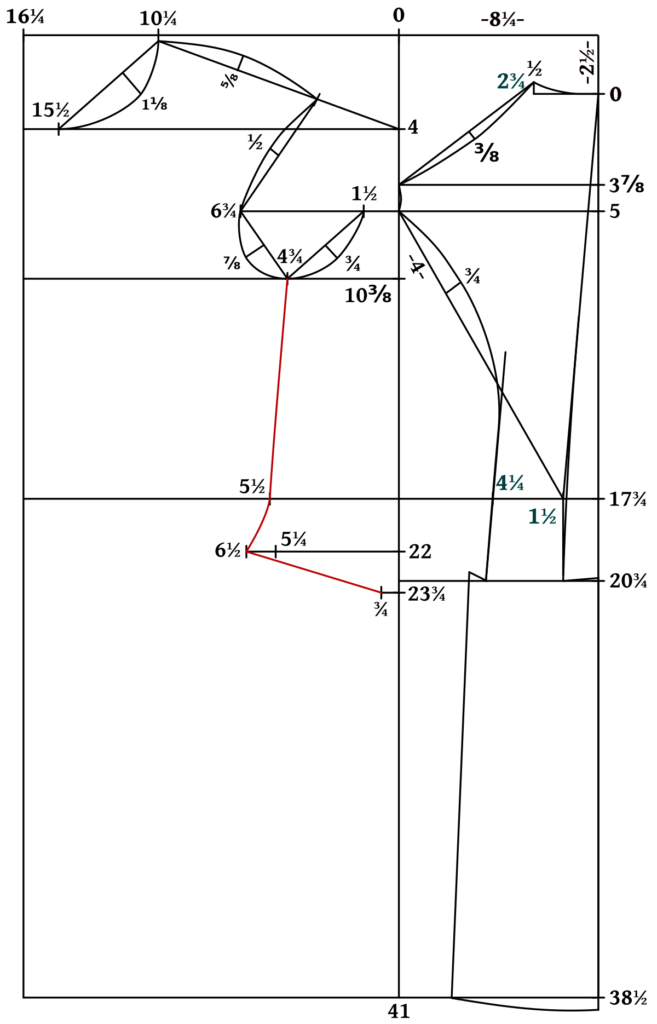

Now draw the construction line for the front shoulder from 1/4 inch below 10 1/4 to 4. Then measure the construction line for the back shoulder and mark the same distance on the front shoulder (from 10 1/4).

Find the center of the shoulder and square up 5/8. Draw a curve connecting the three points.

Draw construction lines for the armscye as shown.

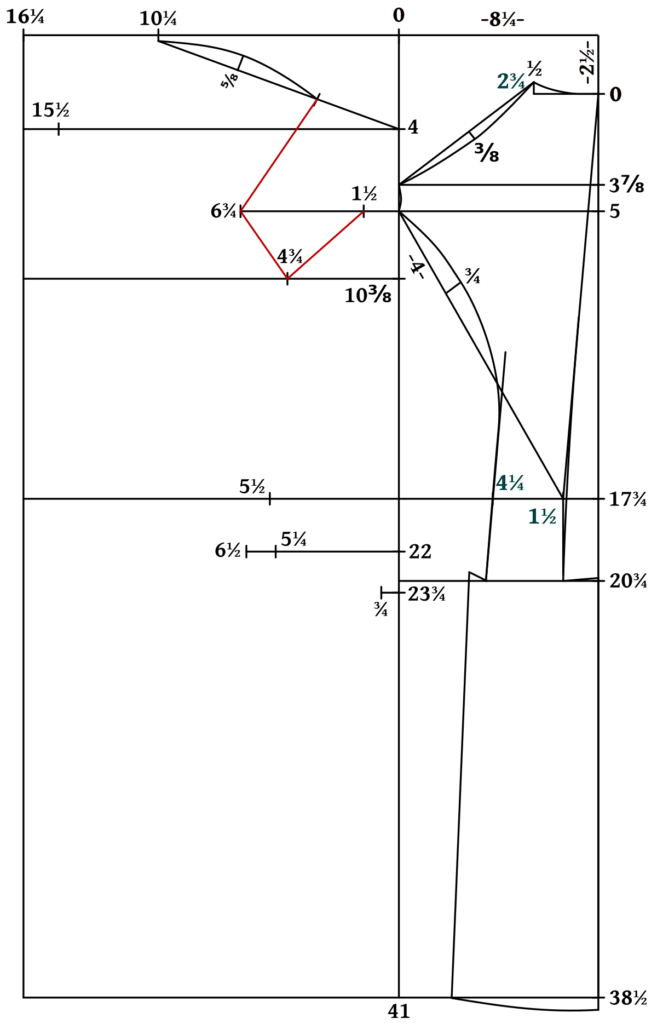

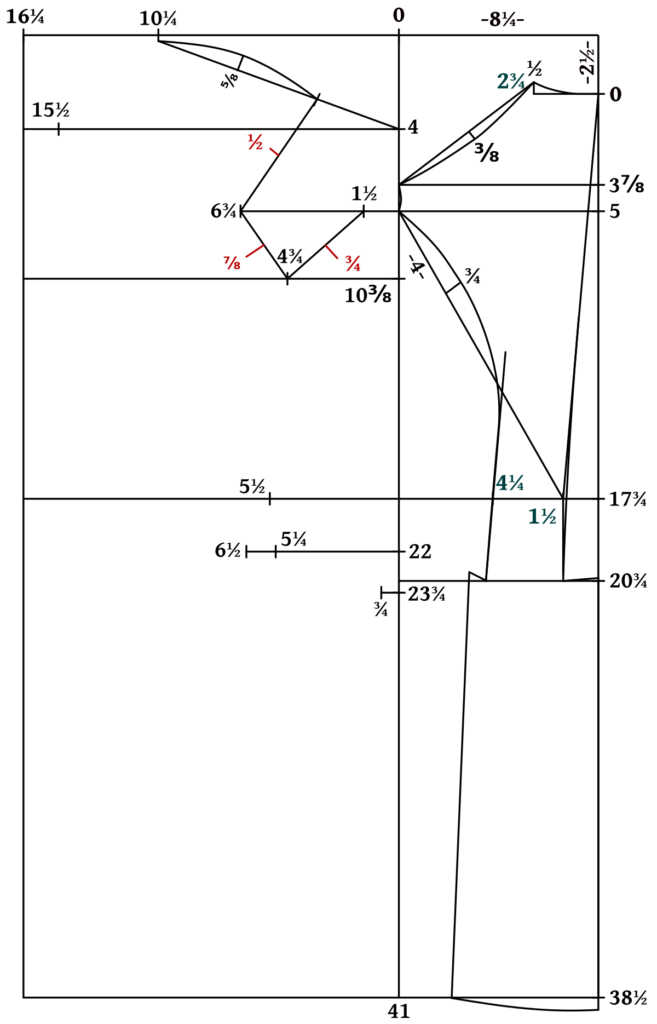

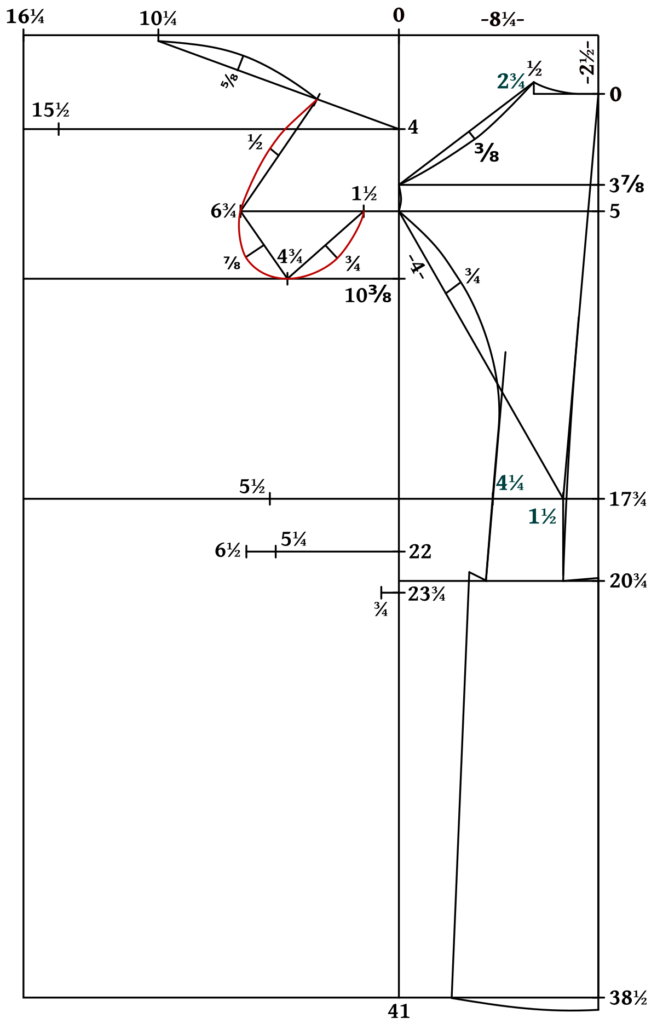

Find the centers of each of the armscyes and square out the distances as follows:

Front armscye: 1/2

Bottom armscye: 7/8

Rear armscye: 3/4

Now draw a graceful, continuous curve around the armscye, connecting the various points as shown.

To find the curve of the neck, make a construction line from 10 1/4 to 15 1/2. Mark 1/3 of the distance from 10 1/4 and square out 1 1/8. Draw a curve connecting the points.

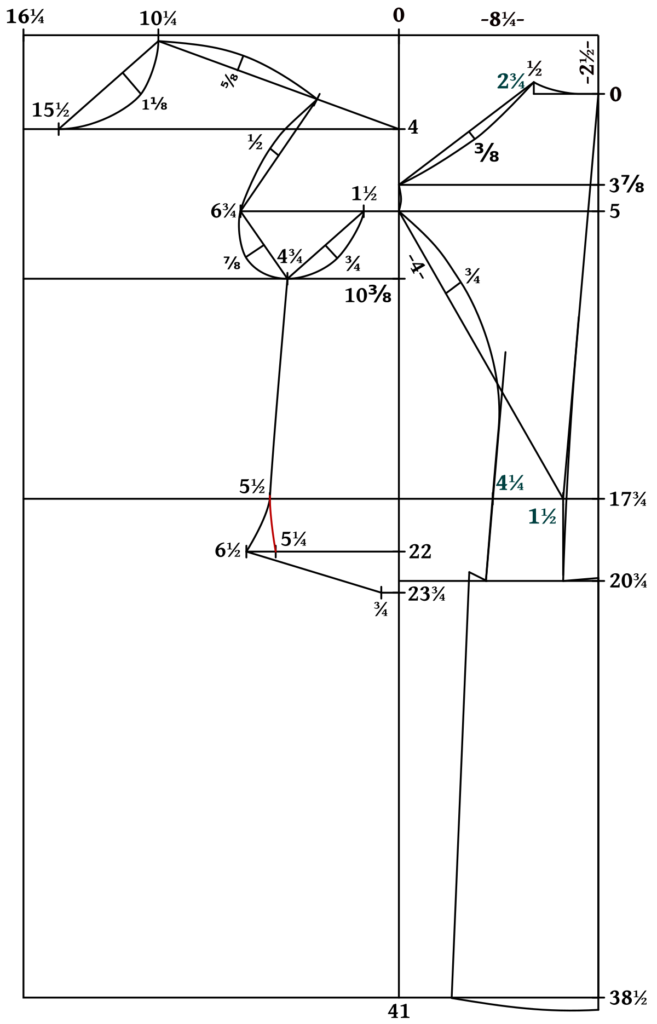

Now it’s time to mark the side seam. Draw a straight line from 4 3/4 to 5 1/2 as shown, gradually curving from 5 1/2 to 6 1/2. Connect 6 1/2 to 3/4 with a straight line for the bottom of the sidebody.

Curve 5 1/2 to 5 1/4 as shown. This gives some spring or room for the hips on the front of the coat.

While we’re at it, now’s a good time to check the length of the side seam from 4 3/4 to 5 1/2 and compare it to the measurement you took. If it’s way off, I’d stick with the measurements from the draft, but feel free to share a photo of your draft and I can take a look.

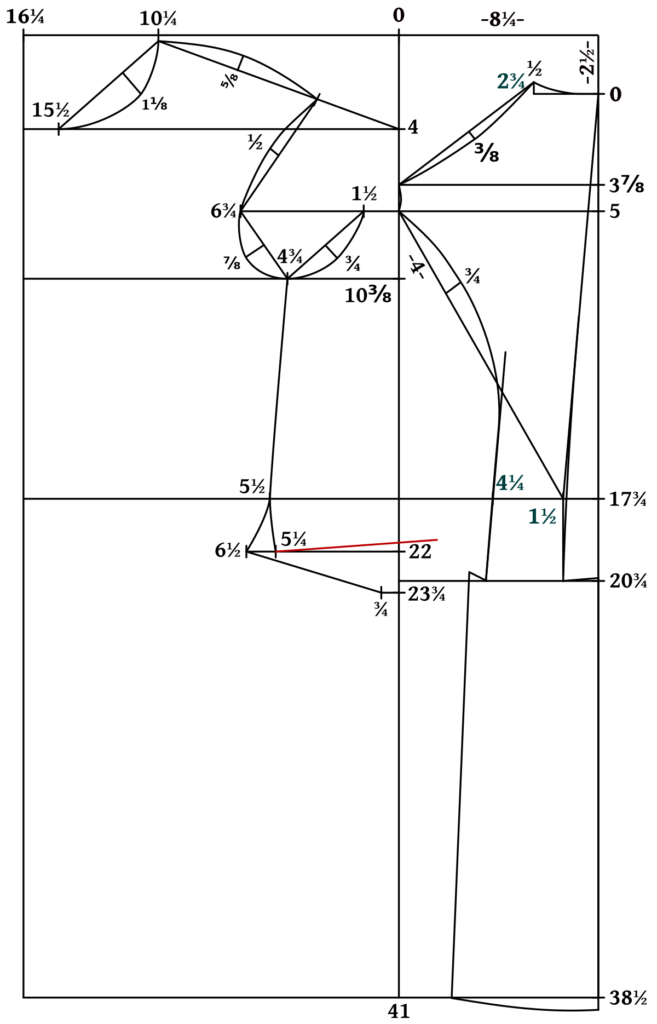

This next step is a little unclear because Devere, the author of this draft, does not give any measurements for this. Here’s what I like to do:

Draw a line from 5 1/4 towards 22, rising up 1/2 as it crosses the construction line from 0.

For the length, make it the same as the bottom of the side body (6 1/2 to 3/4) plus 3/4 for the back of the pleats.

Drawing the curve for the side body takes a little bit of artistry as well as careful calculation. About 2 inches below 10 3/8, square out 3/4. Then draw a curve from 1 1/2 through 3/4 to 3/4 at the bottom. At the bottom, the line should pretty much even out to being completely vertical. This step can take a bit of trial and error but it’s worth the effort.

Now draw the line for the back of the skirt. Devere doesn’t give an angle for this, but 30 degrees from vertical is a good starting point. You can widen the angle if you’d like more room in the skirt. This line should be equal in length to the side of the back skirt.

Now draw the bottom of the skirt, starting from horizontal at the front, landing square at the back of the skirt with a nice gentle curve.

For the front profile, the coat stays along the construction line to the waist. Then it tapers inwards gently to become parallel 1 graduated inch from the front edge.

Finally, at the top of the neck, and the bottom front of the skirt, add a bit of a curve to each of the corners. I used a spool of thread about 1 1/2″ in diameter, you could find something similar to help draw your own.

That complete’s the main part of the draft! Next we’ll add a couple of details and then draft the collar, sleeves, and facings.

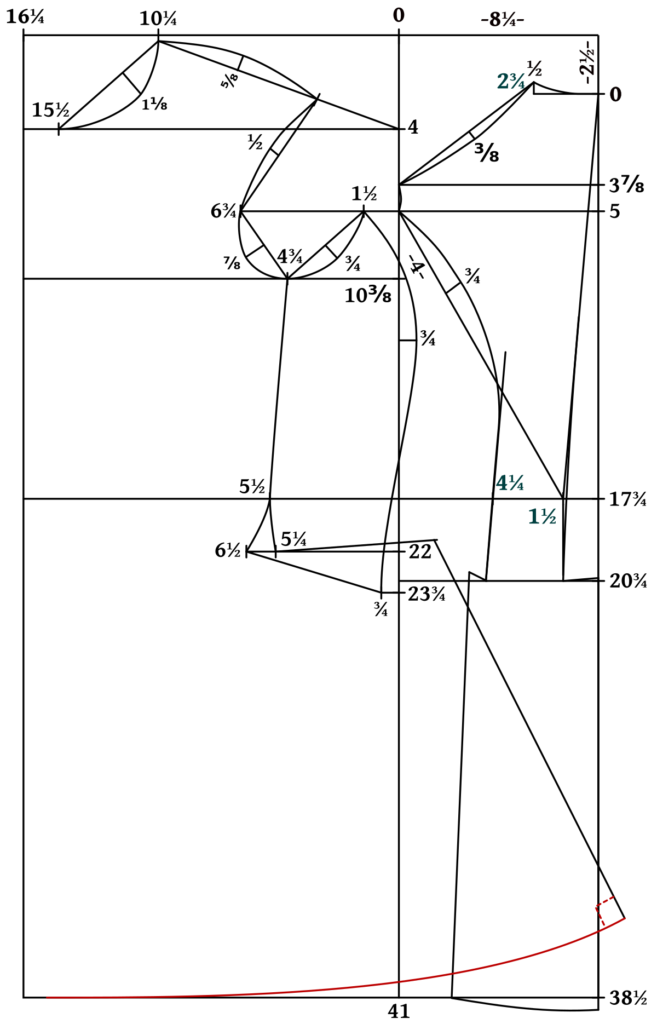

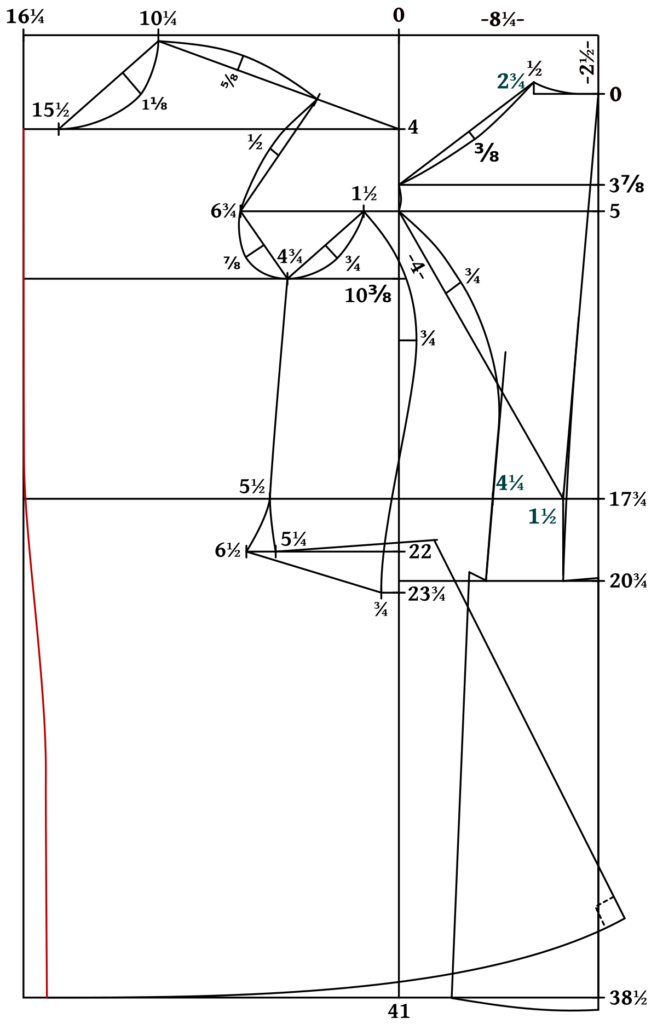

Drafting the Back

Now that your measurements have been taken, it’s time to get started on the drafting process. You’ll need to clear a space on the table or floor to have enough room for the pattern, which needs roughly a 2 1/2′ by 3 1/2′ sheet of paper for the draft itself, depending on your size of course.

I’ve tried to keep the drafting itself as simple as possible for this course. The first and most important thing to do is choose and print out the appropriate size graduated ruler. Take your full breast measurement, say a 42″ breast, and the corresponding ruler in size 42 is what you will use for the entire draft.

To print out the rulers, you need to make sure your print settings are set to scale at 100%. Otherwise, some printers have a tendency to shrink the printout to fit on the paper, which would of course mess up your draft completely. After printing, compare the size 37 1/2 graduated ruler to a regular ruler, and they should be the same size.

Some of the larger rulers are too big to fit an 8 1/2″ x 11″ paper, so they’ll get cut off. Just work in smaller increments – say you need to measure out 23″, measure 5″+5″+5″+”+3″, for example. It’s a pain but works in a pinch.

As you go along, there are places where you can check your actual measurements against the draft, to look for any gaping errors. I’ll point those places out along the way as we go. All measurements are in the graduated measures, unless otherwise noted.

Finally, use a nice sharp pencil when drafting, so you can easily correct mistakes. Taking care with the details of the drafting process will help the fitting and subsequent steps go a lot more smoothly.

Drafting the Back

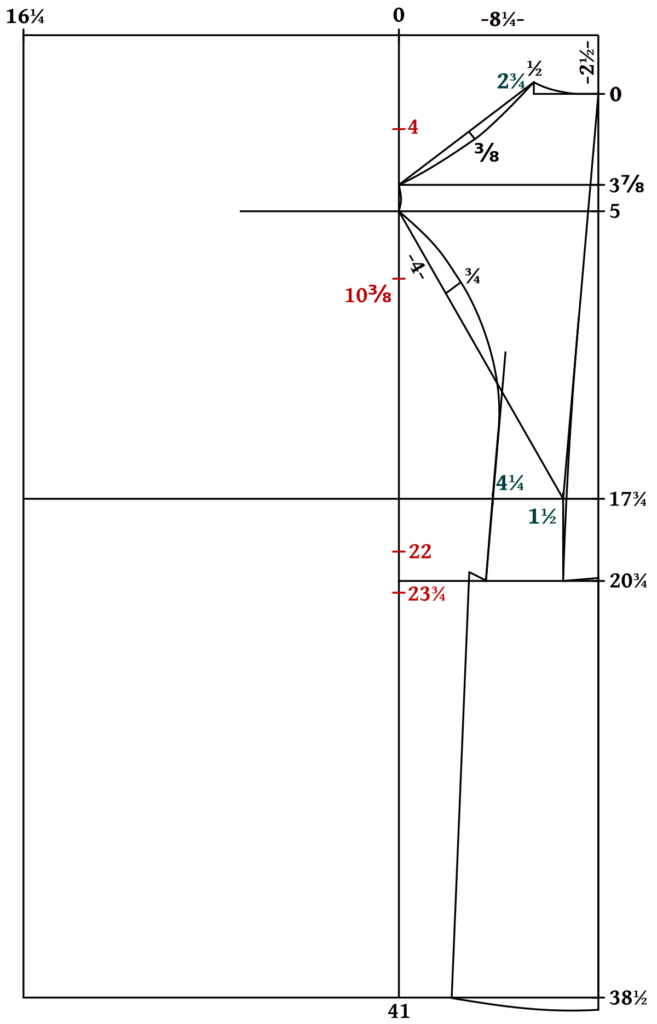

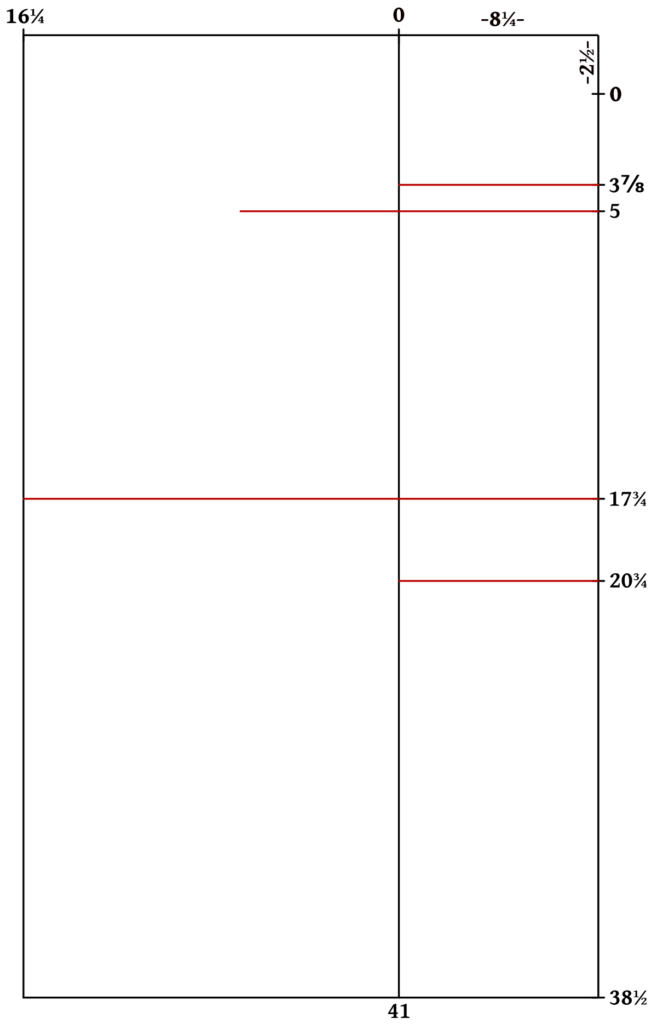

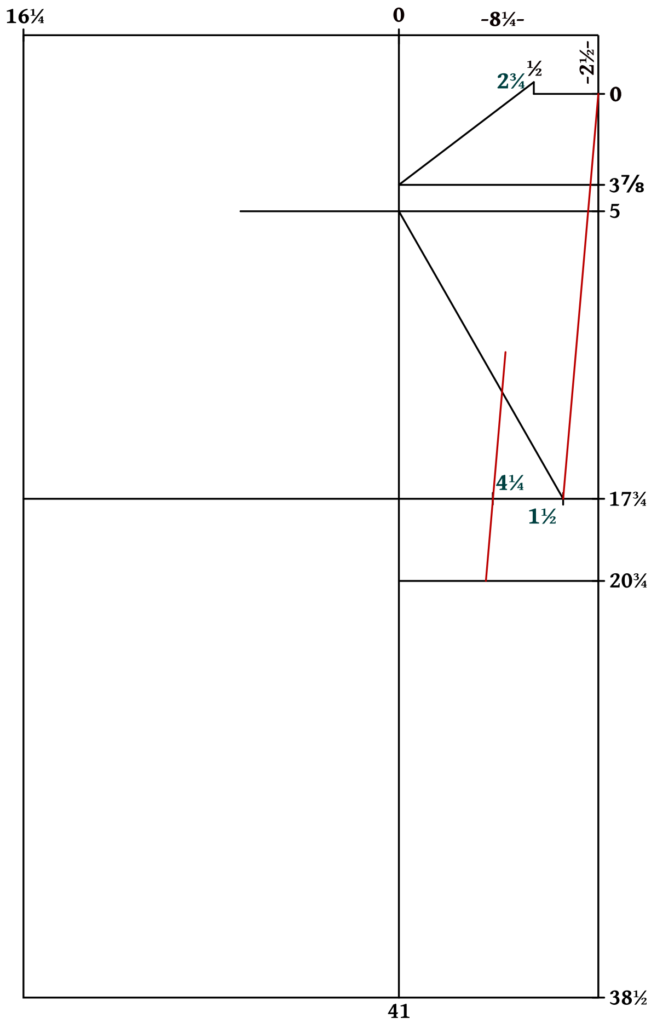

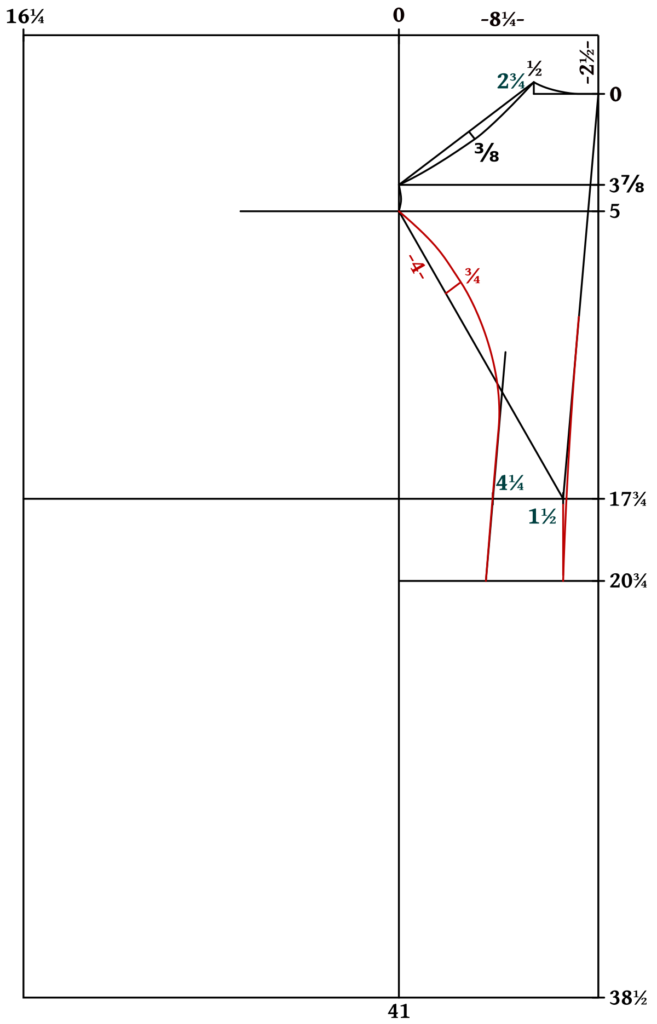

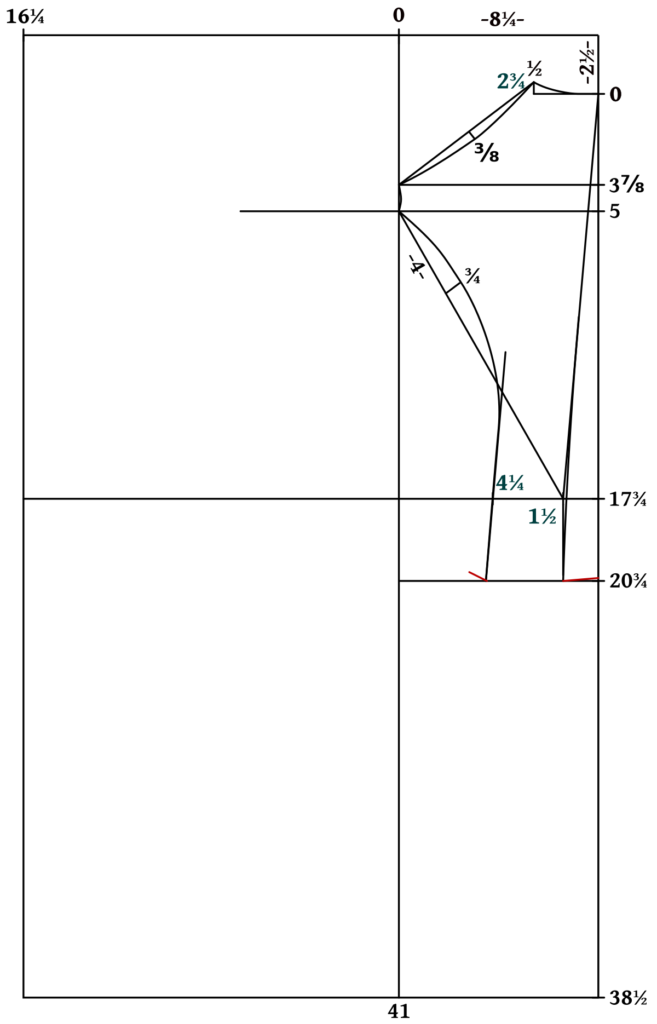

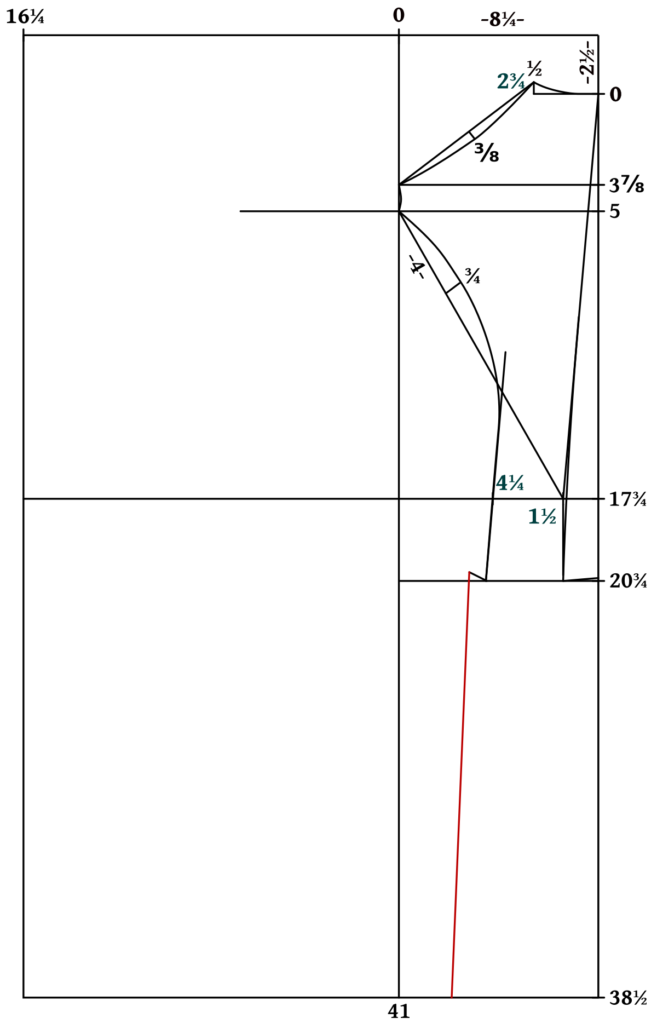

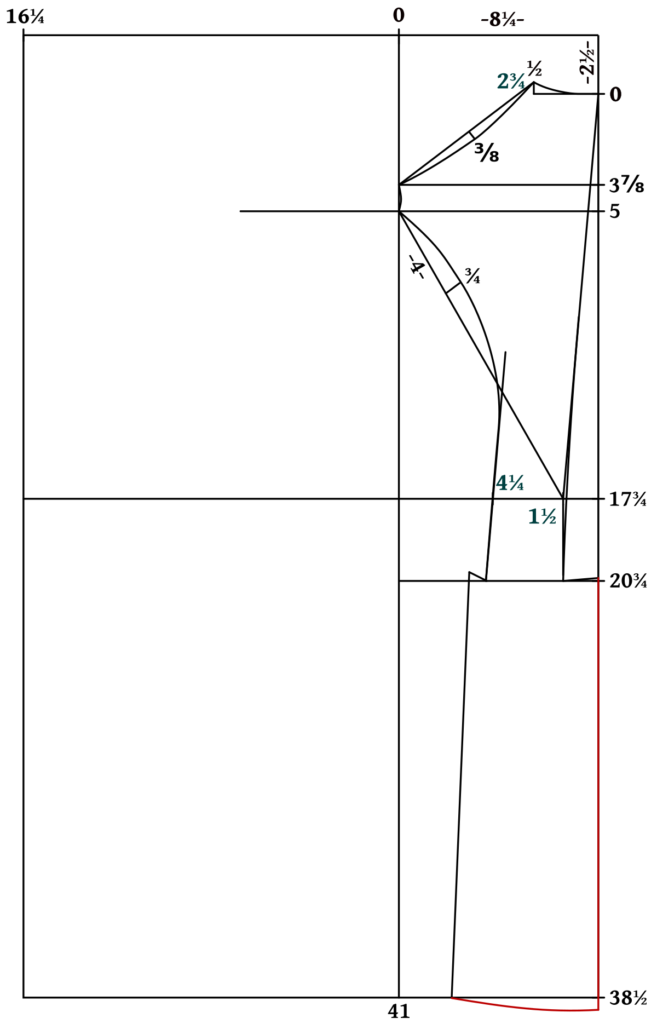

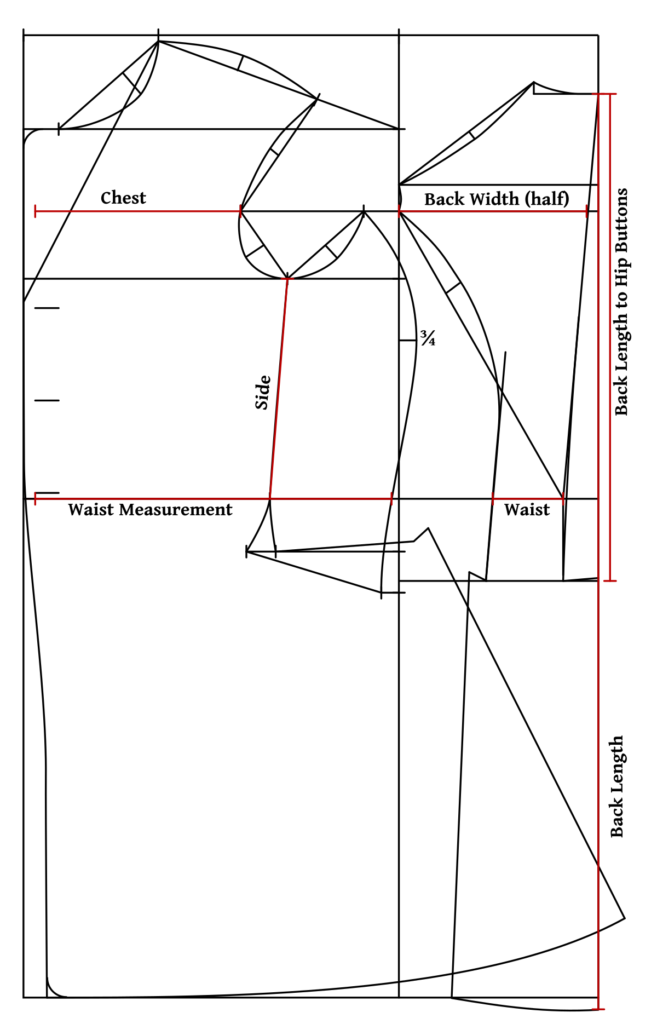

To begin the draft itself, you must first layout what’s called the square. Draw a vertical line down the right side of the paper, connected to a horizontal one at the top. Mark the measurements as shown with your graduated ruler, noting carefully where the 0 points are. There are two 0 points in different locations, which can make things confusing if you forget that later on. All measurements are taken from the 0 points accordingly.

You can compare the distance between 0 and 38 1/2 to the measurement you took for the length of the coat. Feel free to adjust this if you’d like, now’s the best time to alter it!

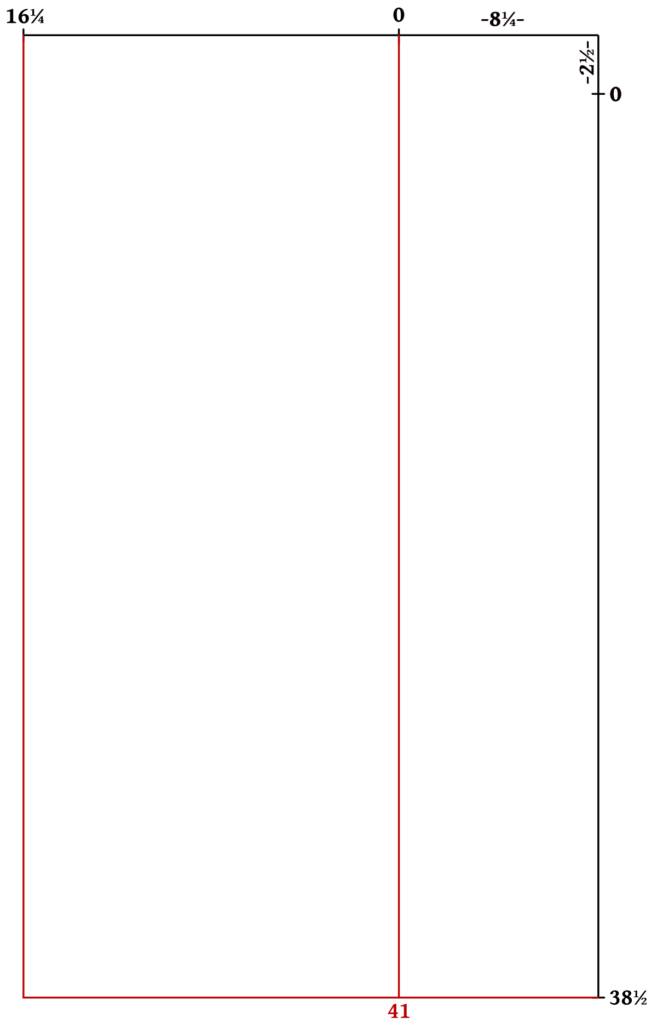

Complete the square as shown, squaring down from 16 1/4 and 0, and across at the very bottom.

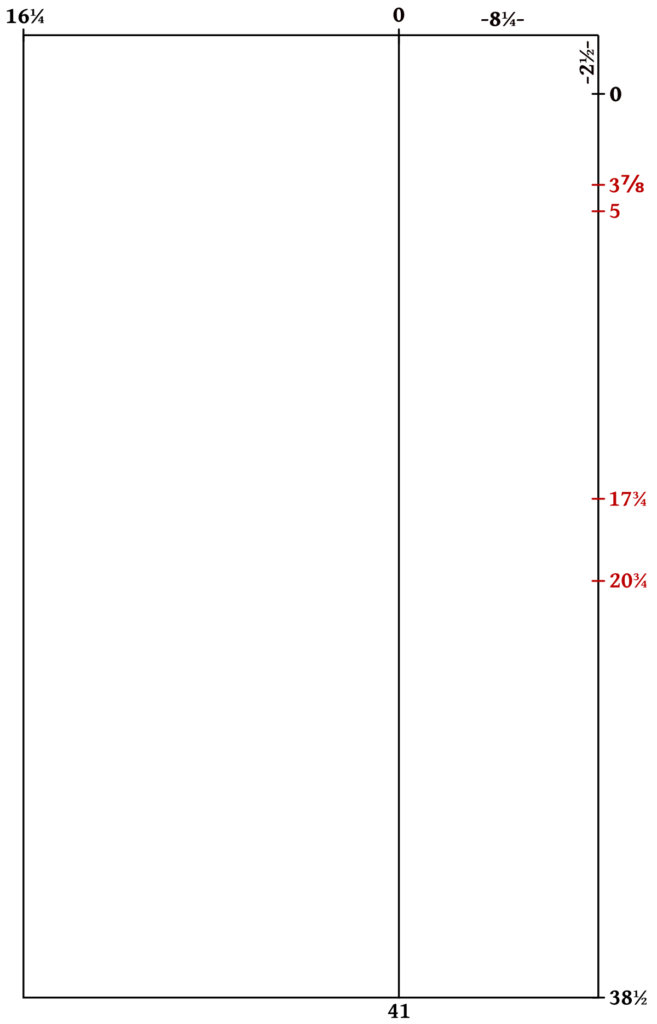

Along the right side, mark the various lengths as shown, being sure to measure from the 0 point, not the top of the square.

Square out, as tailor’s refer to it, or draw lines perpendicular to the measurements you just marked. At 3 7/8 for the bottom of the shoulder. At 5 for the top of the side seam, extending that past the dividing line a bit. At 17 3/4 extend the line all the way across – this is the waist line. And finally at 20 3/4 for the top of the pleats.

You can compare the distance between 3 7/8 and the construction line from 0 with the Width of Back measurement you took. If something looks way off, stick with the draft, but feel free to about it in the Facebook group and I’ll see if I can figure out what’s up.

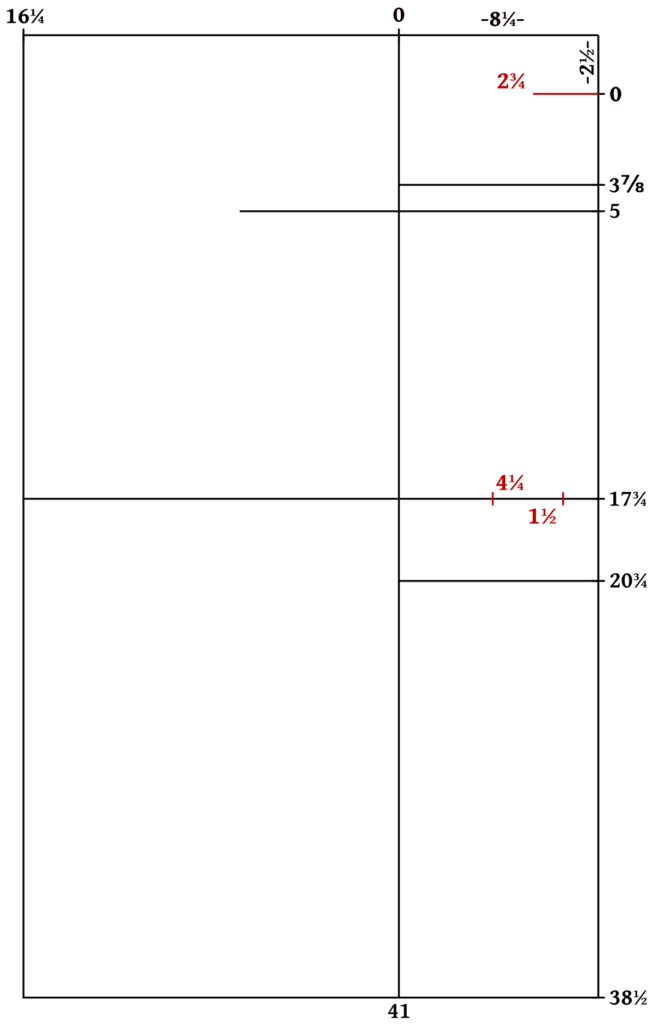

At the 0 mark square out 2 3/4 for the neck.

On the waist line, mark points 1 1/2 and 4 1/4 away from the right construction line. This gives the width of the back at the waist.

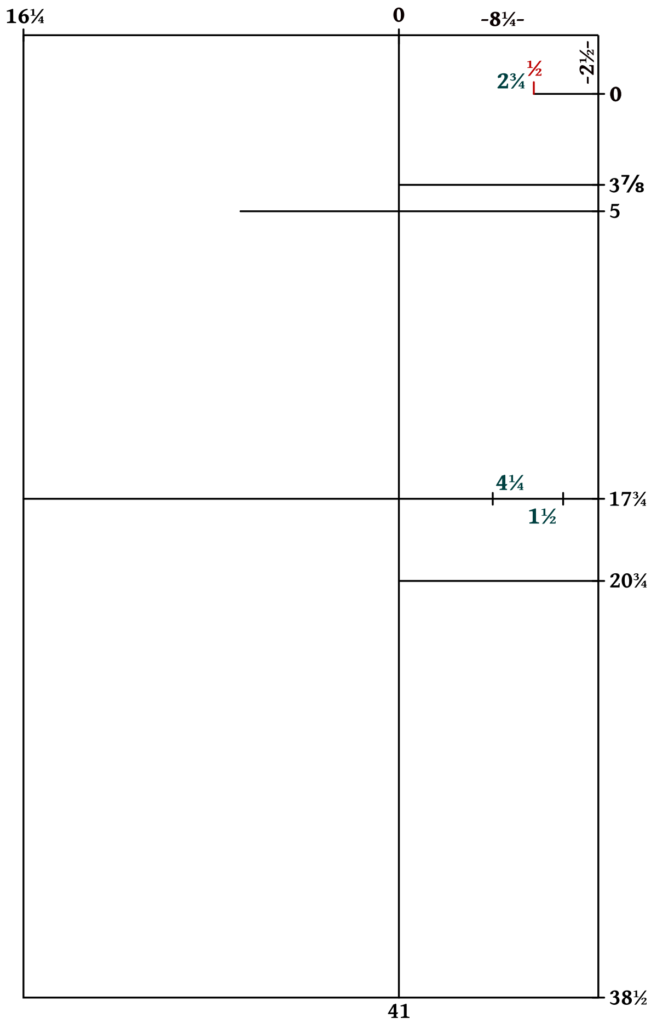

At the neck, extend the point up 1/2 inch.

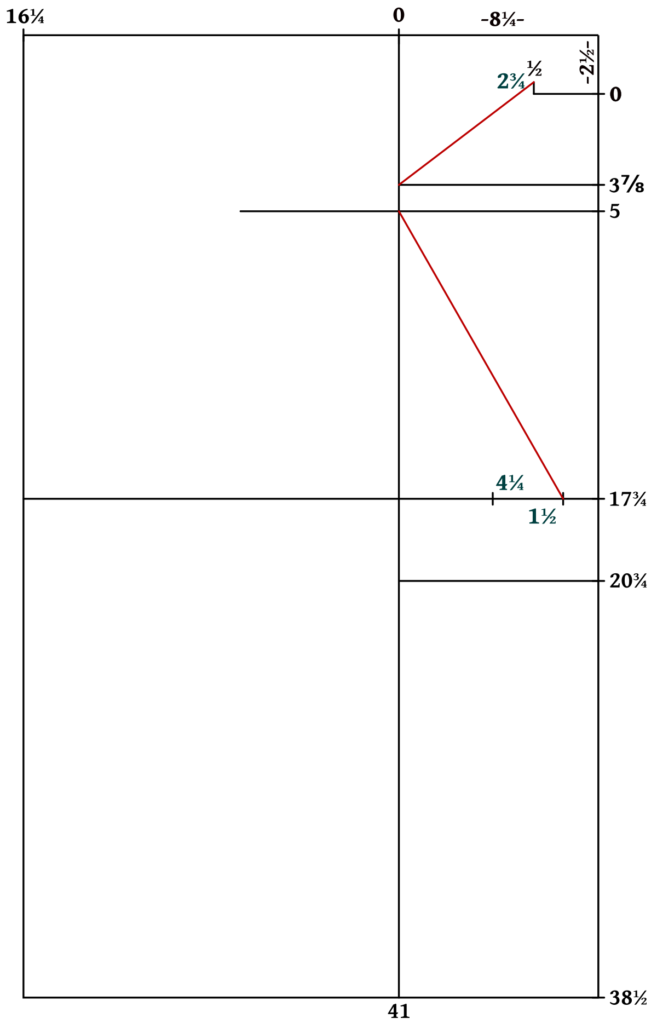

Draw construction lines for the shoulder and side seam as shown.

Draw a line for the center back from point 0 to the 1 1/2 mark at the waist line.

Draw a parallel line to this at the 4 1/4 mark on the waist line, extending up past the side seam construction line, and down to the pleat construction line.

Here’s a good place to compare your actual measurements to the draft using the Back to Hip Buttons measurement. Compare that length to the distance between 0 and 20 3/4. If you’re very good at measuring they should be almost exact, but if your off by up to an inch or so, I’d leave the draft as is and see how it turns out in the fitting.

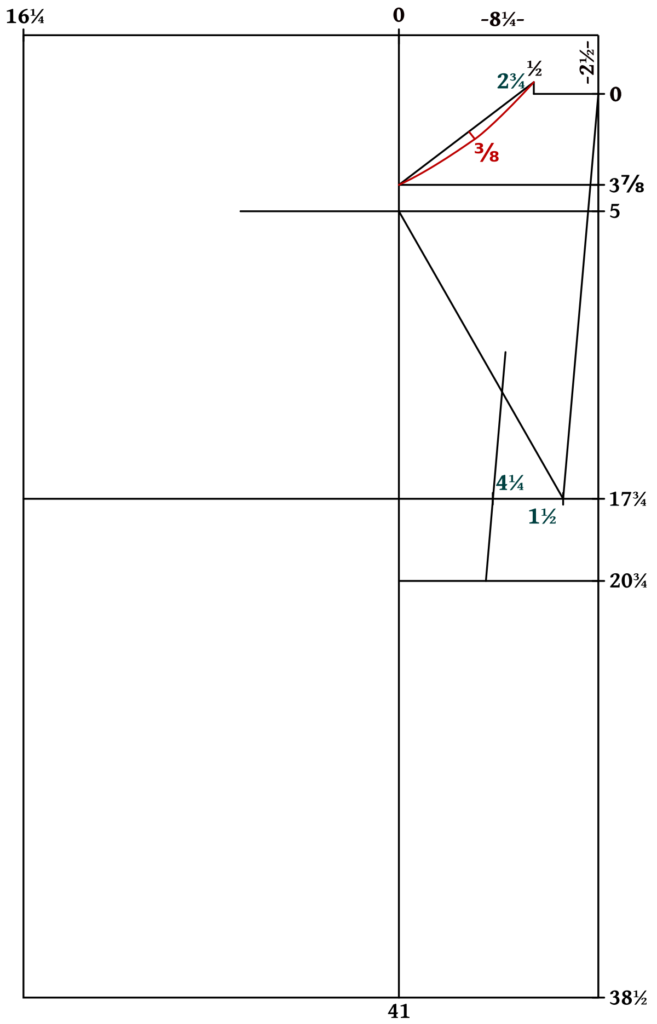

Now we’ll start to draw some of the curves for the back. Find the center of the shoulder construction line. Mark a line inwards 3/8. Connect the three points in a graceful curve, either by hand, using your arm as a sort of compass, or you can use a french curve or a bendable drafting ruler if you have one.

Draw the neck curve as shown.

This is a little hard to see, but right below the bottom of the shoulder, on the middle construction line between 3 7/8 and 5, draw a small curve for the back of the armscye. This should curve in about 1/8 inch.

Along the side seam construction line, measure down 4 as shown. Then square up from there 3/4. Draw a nice curve from the bottom of the armscye down towards that construction line for the back, tapering gradually as you get towards the bottom.

On the other side, the center back, square down from 1 1/2 to the pleat line. Then draw a gentle curve blending the two straight lines of the center back into one.

At the pleat line, on the right side, draw the pleat ‘springing up’ about 1/8 to 1/4 at the center back.

On the left side, spring up about 3/8, and make the line 7/8 total in length.

Draw the pleat side of the back skirt as shown. The bottom should be 3/4 wider than the top.

At the very bottom, square out from the pleat side and gradually curve the bottom so that the center back side meets squarely as well. Leaving things not squared leads to unsightly dips in the hem later on.

The back piece continues back upwards to the top of the pleats following the original construction line.

And this completes the draft for the back piece! On to the front now.

Measurements

The first thing to do in preparation for making a coat is to take good, accurate measurements. Since this is more of an introduction to coat making, I’m going to simplify the measurements as best I can to make it easier for you to get started right away.

All measurements should be taken over what you will wear underneath this coat, if possible. That’d mean a period shirt, trousers, and waistcoat if you have them. If not, I’d recommend adding maybe an inch to your measurements if just measuring over a regular shirt, for example.

A good idea for beginners is to tie a length of twine or ribbon around the natural waist so that all of your measurements are referenced from the same points. This should be tied around the waist at about the level of the naval.

While it’s possible to measure yourself – I do it all the time – for beginners I’d recommend having someone measure you if you can. If all you’ve got is your self, that’s fine too! You’ll just have to contort your arms into various positions while trying to keep your body as straight as possible.

And in general, try to keep your body relaxed in its natural position when taking the measurements. Don’t try to stand extra erect like a dashing officer if you don’t stand like that in real life, for example.

With that all said, on to the measurements!

Measurements

There are a number of measurements you’ll need to take for your coat. I’ve included a chart in which you can right them all down for convenience. Listed out, you’ll need the following measurements:

- Breast (written as half the actual measurement)

- Waist (written as half the actual measurement)

- Total Length

- Back Length to Hip Buttons

- Side

- Chest

- Width of Back

- Sleeve

- Sleeve + Back (optional)

Breast

This is the most important measurement and determines which size of graduated ruler you will use for your draft. Measure around your chest at the fullest point, just under the arms. Take note of the full measurement to choose your ruler size, but the measurement is written down as half of the total, since we are drafting half of the pattern on the paper.

Waist

The waist measurement is taken at the level of the natural waist, about even with the naval. Again this is written as half for use when drafting.

Total Length

Measuring down the center of the back, start at either the base of the collar or at the 7th vertebrae if you don’t have period clothing available (the bony part on the back of your neck). Measure from there, pressing the tape against the hollow of the back, down to the bottom of where you’d like the coat to be. This is mainly a check measurement to compare with what we’ve drafted later on.

Back length to Hip Buttons

Again starting at the base of the collar, measure down the center of the back to the position you’d like the back hip buttons to be, usually a couple of inches below the natural waist. This is another check measurement to compare with the draft.

Side

Put the measuring tape under your armpit, though not too high up, and measure straight down to the waist seam. Yet another check measurement!

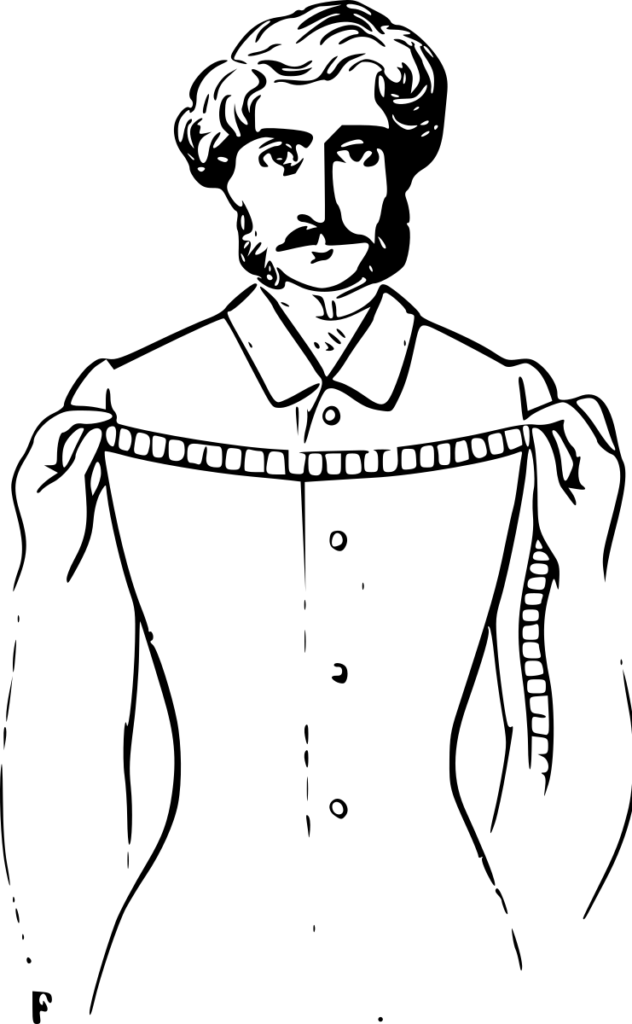

Chest

Sometimes when drafting, especially with these older drafting systems, our body’s widths will not be perfectly distributed from front to back. This is a good measurement to take to compare with the front of your draft.

The chest measurement is taken across the fullest part of the chest, from armscye seam to armcye seam.

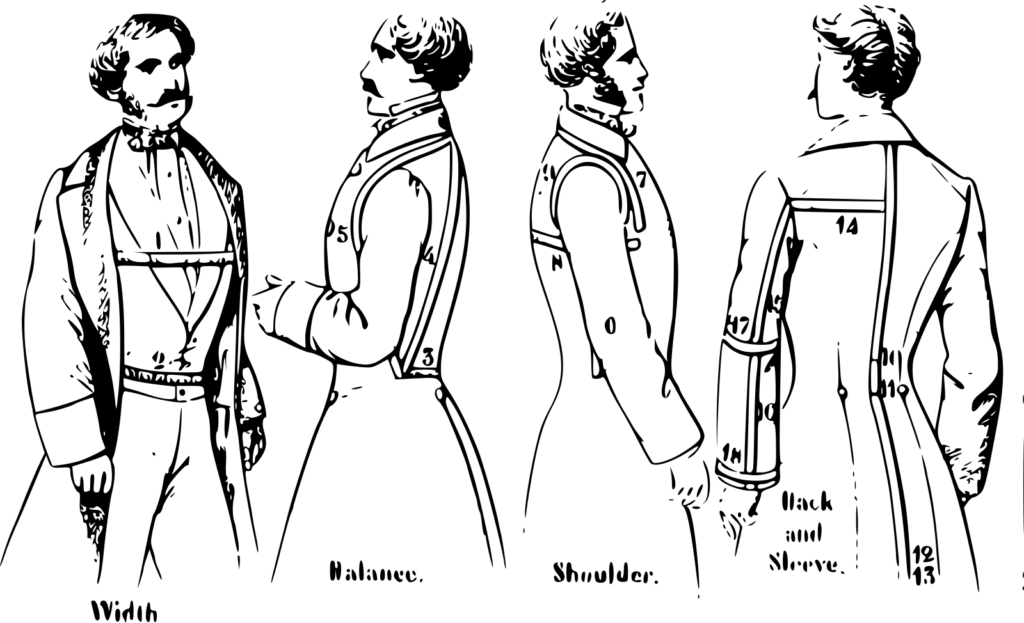

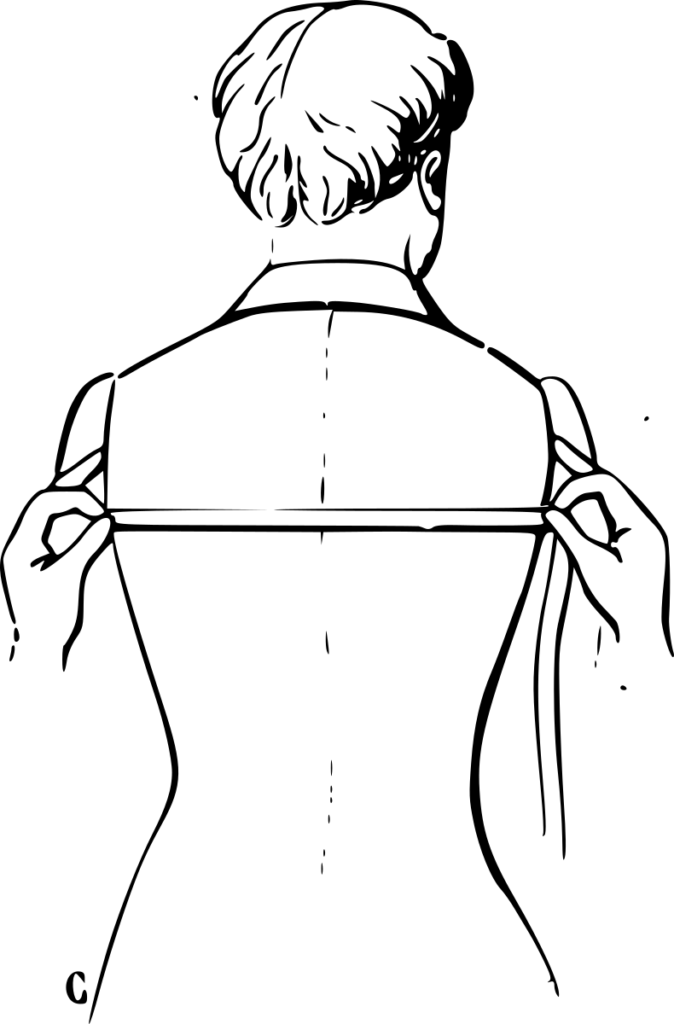

Width of Back

This is similar to the chest measurement, but taken straight across the back from armscye to armscye at a level just at the bottom of the armpit.

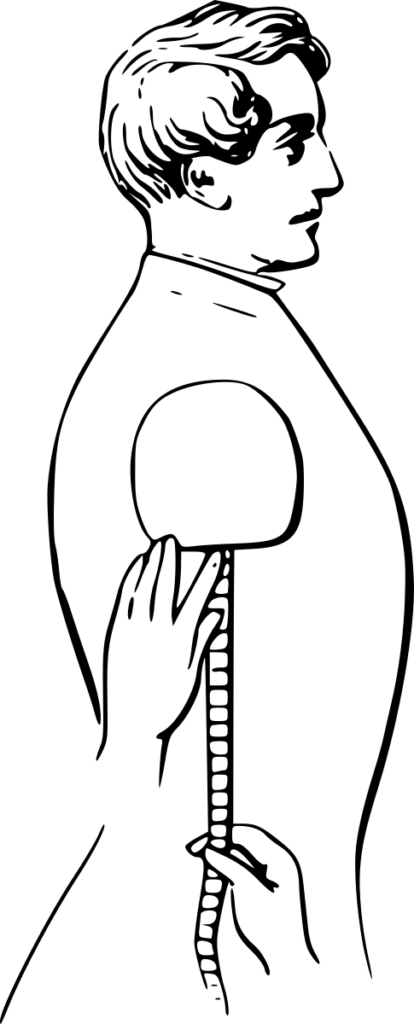

Sleeve

The sleeve can be a little troublesome to take, especially for a beginner, but it’s easy to fix during the fitting process if necessary.

To take the sleeve measurement, stand with your arm extended horizontally, and bend the elbow at 90 degrees. Measure from the armscye along the back of the sleeve, around the elbow, to just past the wrist (sleeves were longer in the 1860s than they are today).

You can also take the same measurement from the center of the back, that way you can compare the two measurements and look for any discrepancies. I’ve included a video demonstrating the two measurements.

How to Use the Measurements

As you’re drafting, take note of the various lines in red, and compare their lengths to the measurements you took. If they’re far off, it indicates something may be wrong, and that you should investigate before moving on and compounding the problem. This can happen especially with larger sizes, above size 46 – 48.

Button Catch Lining

After cross stitching, it’s time to install the button catch lining. Lay the pieces wrong sides together.

Baste down the center of the button catch, stopping an inch or two from the bottom so that there is room to turn under the edge after.

Turn under the raw edges and baste securely closed. I like to start with the straight edges and work my way down towards the curved bottom, which is a bit fiddly to get it looking just right.

Finish turning under the edges at the very bottom.

Using a small felling stitch, fell the folded edge of the lining to the button catch. I use about 8 stitches per inch, entering the lining fabric with the needle from the top, catching the wool underneath on the diagonal, keeping the visible part of the stitch very small and straight. This also gives better tension to the lining when sewn in this manner.

I like to start at the waist, sewing down towards the bottom of the button catch, and back up the other side.

Trim off any excess lining.

Interlining

An interfacing of linen is now added to the button catch to provide additional strength to the area and keep the buttons from tearing out over time. In the past, I’ve used a single layer of linen cut to the shape of the fly pattern piece, but these days I’ve taken to using three layers.

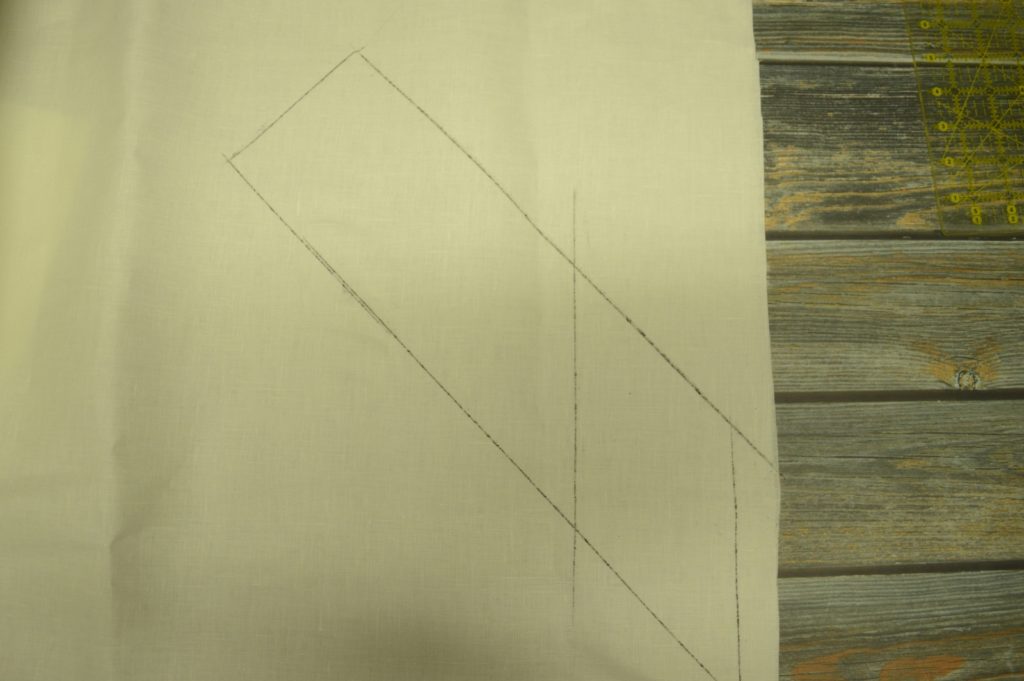

Begin by measuring the width of the button catch, subtracting the seam allowance from that measurement. Then cut a bias piece of linen three times that width, and a little longer than the fly itself.

Cut out the linen. Note how I left the triangular piece on the end rather than cutting it square.

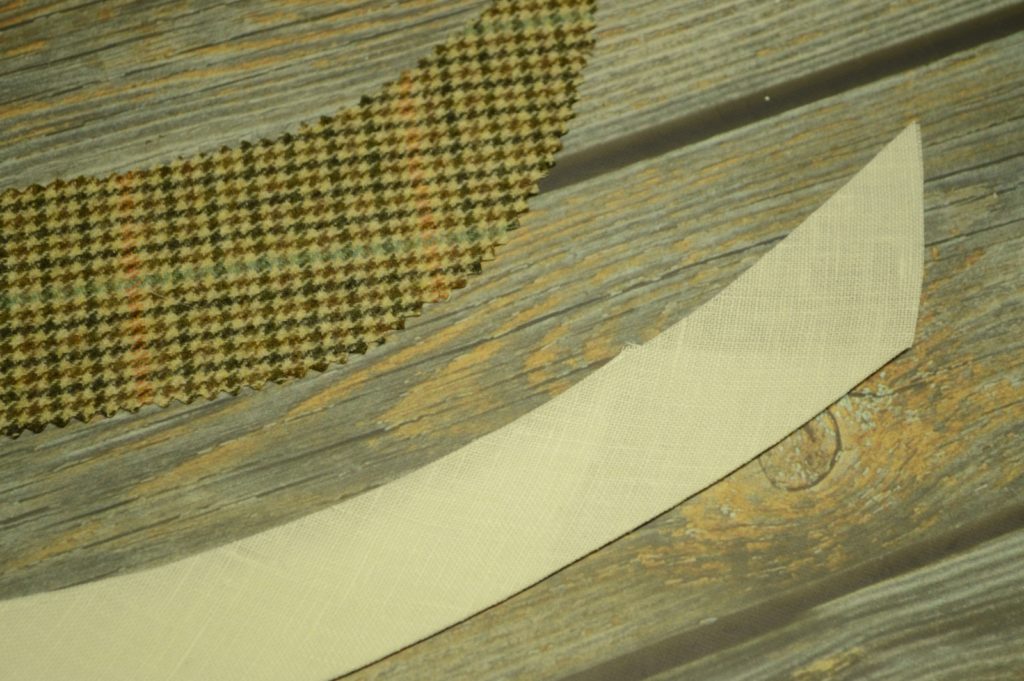

Now fold the linen into thirds, pressing firmly. The pointed section should be towards the bottom of the fly to gradually reduce bulk in that area. Stretch the lower end on one side to match the curve of the button catch as best you can. Sorry I didn’t get photos or videos of this for some reason!

You can see how the layers thin out towards the bottom. We’ll be top stitching through the button catch and fly later on, and if all three layers were present there, it would be very difficult to almost impossible to sew through all of the layers.

Lay the linen interfacing into position on the wrong side of the button catch. The inner edge should fit underneath the seam allowance, while the outer edge should be 1/4″ from the edge. If that’s off, however, you can trim it after basting.

Starting from the bottom of the button catch, baste the interlining into place. Trim any excess out of the seam allowances if necessary (shown in the video below).

Now fold the outer seam allowance on to the linen and baste securely in place. You’ll have to fiddle a bit with the bottom of the button catch where the two seam allowances meet.

Now cross stitch the seam allowance to the linen, being sure not to let the stitches show through to the right side.

Trim any excess linen off the top edge, if you haven’t already.

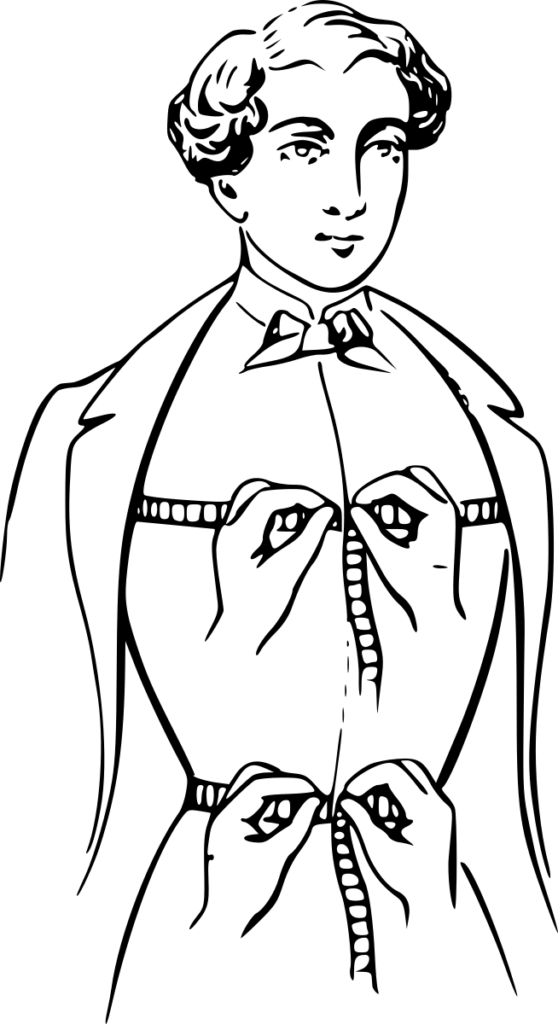

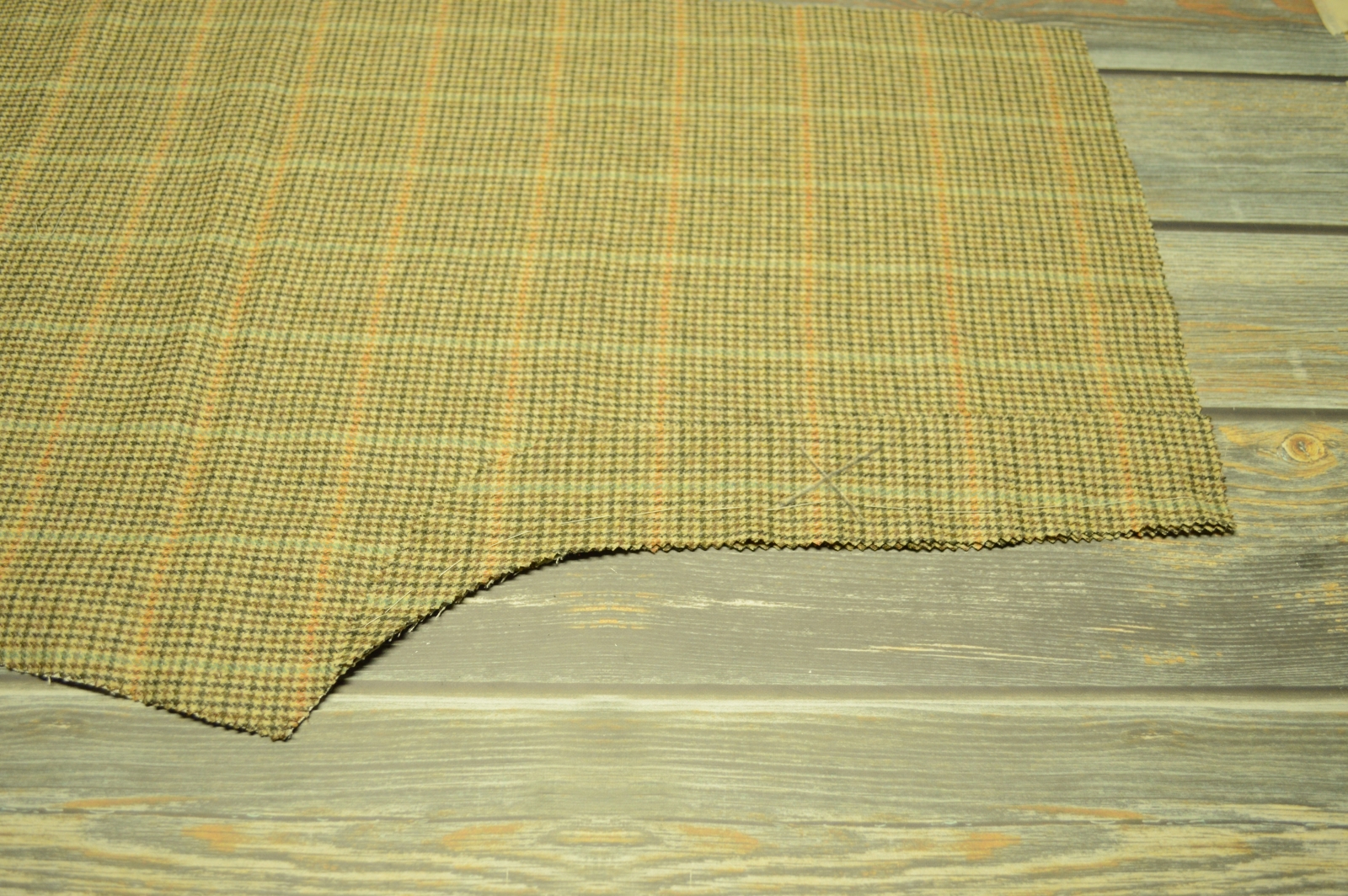

The Button Catch

Now it’s time to begin work on the trouser fly, starting with the button catch. This is where you’ll be attaching the buttons later on. Begin by laying a trouser fly piece on to the right half of the trouser front, right sides together.

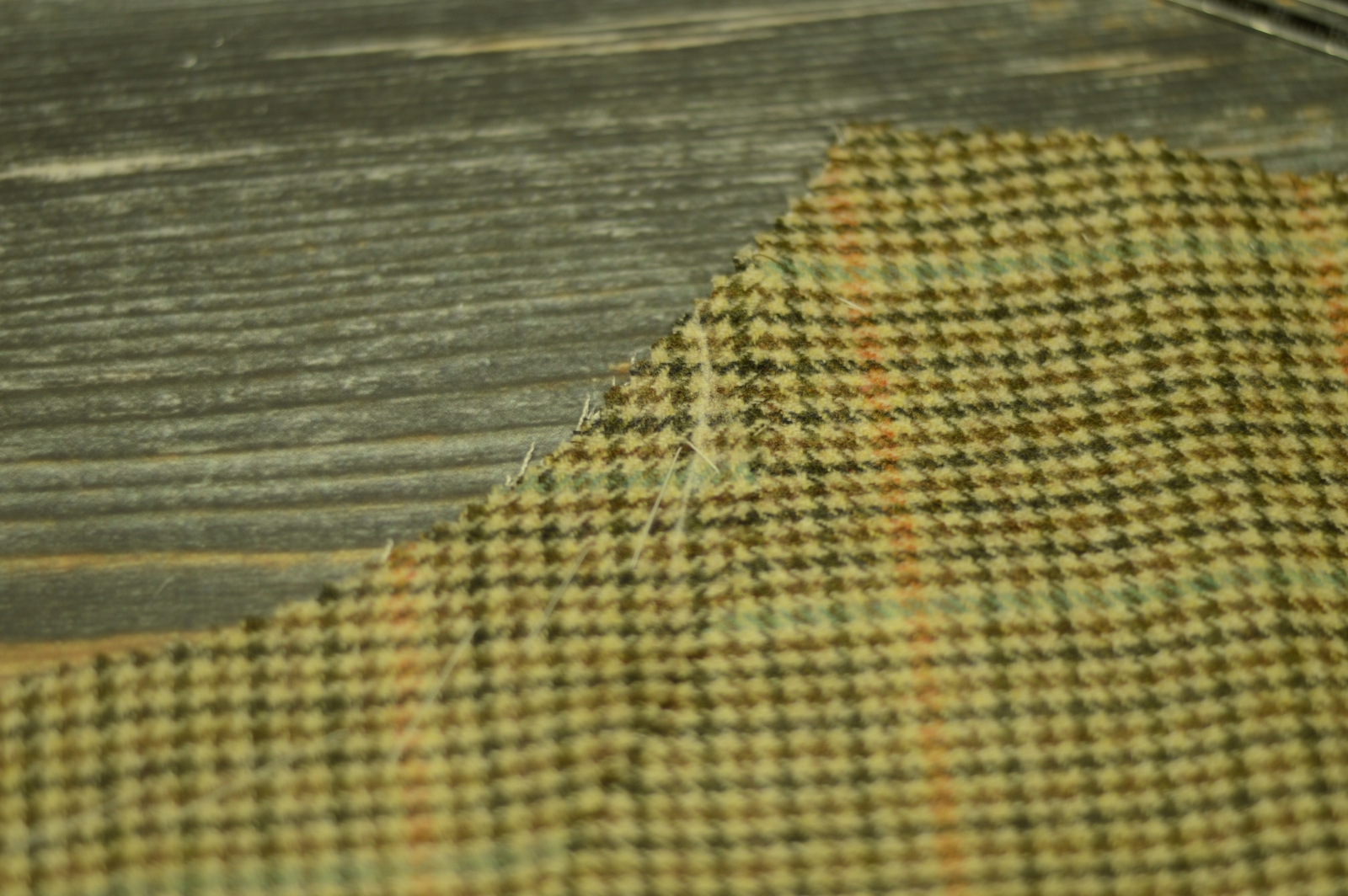

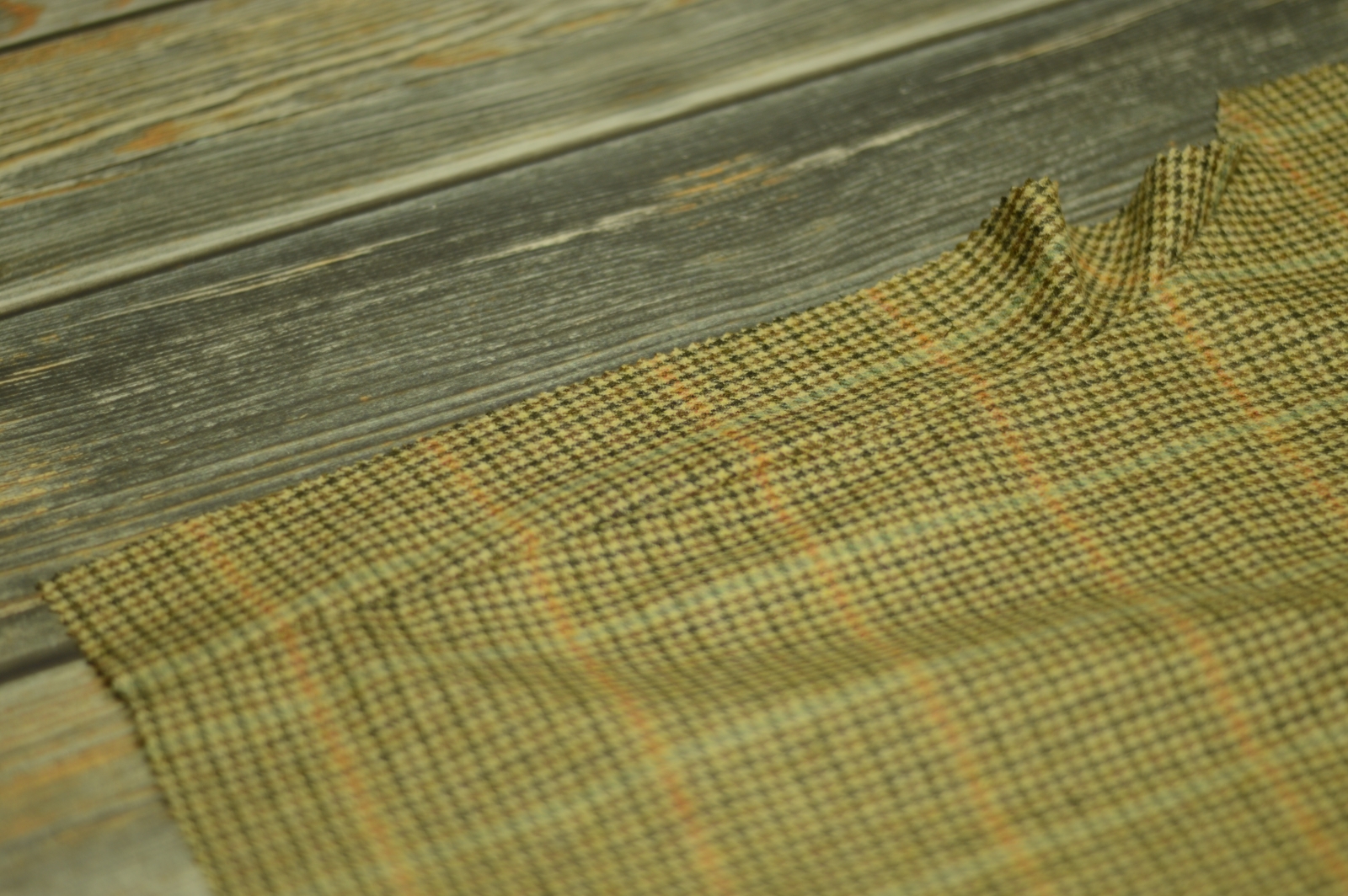

Make fine adjustments as necessary to ensure that the stripes will line up as closely as possible.

Baste the button catch to the trouser securely.

On the bottom / outer edge of the button catch, mark the seam allowance as shown. This is just to show you where to stop sewing in the next step.

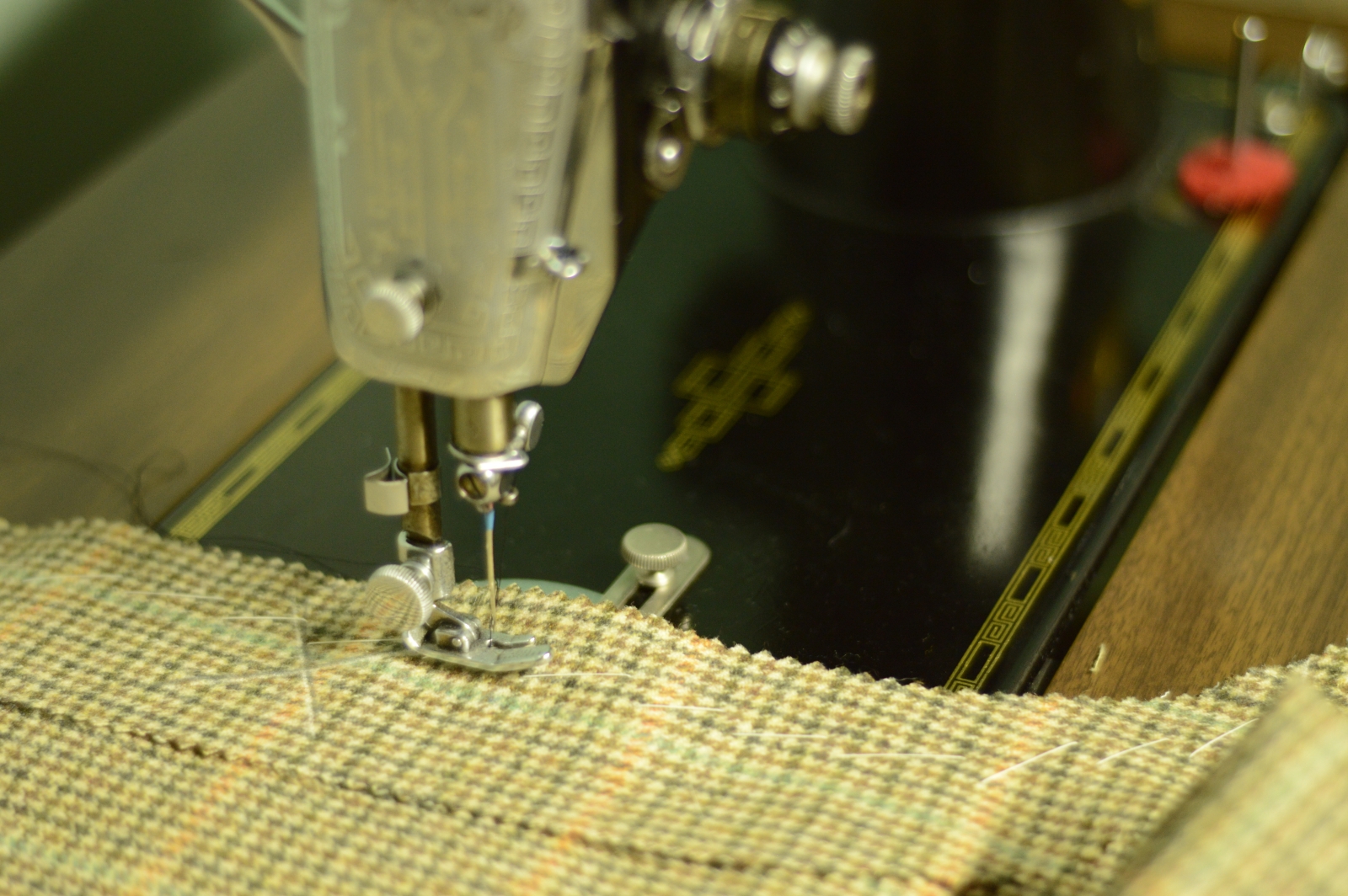

Using a machine or back stitch, stitch the button catch to the trouser front starting at the waist band, through to the mark you made previously, using a 1/4″ seam allowance.

Try to stop as close as you can to the chalk mark. I’m slightly short of it here but it’s close enough. If you’re too far off you may run into trouble fitting the fly to the button catch.

Remove the basting stitches.

Press the button catch seam from both sides with a bit of steam to set the stitches and make the fabric more supple.

Turning to the inside, press the button catch seam open, using a tailor’s ham for the curved areas as necessary.

Press again from the outside to get a firm, crisply pressed seam.

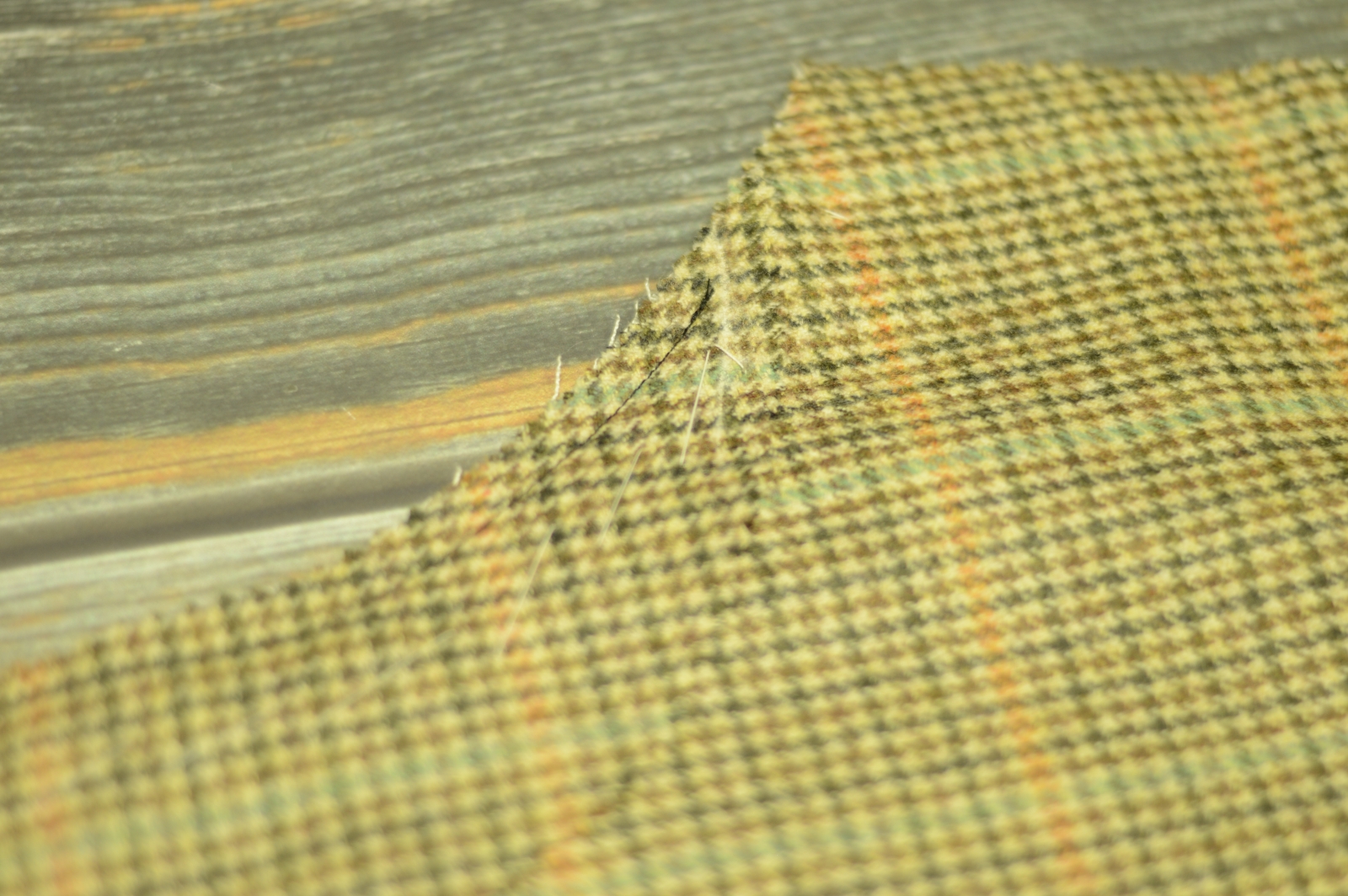

Here’s my final result. I ended up removing the button catch and shortening it by an inch or so to get rid of all those puckers near the end. While you’ll always have a few, due to the curved seams, this told me my fly was just a bit too long.

This is about as close as I could get the seams to match. If I finessed it a little more during the basting stage, it’s possible to have lined up the orange stripes a little better. Really though, no one is ever going to see the button catch so it’s not that important. Just good practice for that stripe matching!

And here’s the video showing the entire process so far.